The state of media freedom in Hong Kong and Taiwan is significant in part because news outlets in both places have in the past provided comprehensive, independent coverage of China, filling a gap left by the tightly restricted mainland press. Any rise in interference, including self-censorship, would imperil the ability of the Hong Kong and Taiwanese press to play a watchdog role.

“Self-censorship–it’s like the plague, a cancerous growth, multiplying on a daily basis,” former journalist and current Hong Kong legislator Claudia Mo said. “In Hong Kong, media organizations are mostly owned by tycoons with business interests in China. They don’t want to lose advertising revenue from Chinese companies and they don’t want to anger the central government.”

That should not be surprising. More than half of Hong Kong media owners have accepted appointments to the main political assemblies of China–the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). Recent appointments to one of the two assemblies include Charles Ho of the Sing Tao news group, Richard Li of Now TV and the Hong Kong Economic Journal, and Peter Woo of i-Cable television. Journalists and academics say they are concerned that the city’s media leaders are being absorbed into China’s political elite.

Adding to concerns in the territory is a series of physical attacks on journalists, as well as steps taken by the local legislature that would hamper reporting.

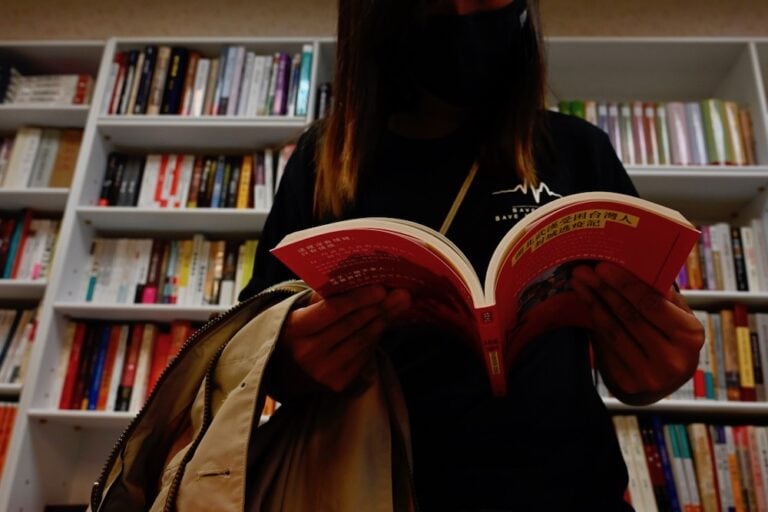

Meanwhile, in Taiwan, many media owners have close business ties to Beijing, which they are loath to jeopardize by drawing disfavor on the mainland. The Taiwanese press is also vulnerable to financial intervention in the form of advertising by Chinese interests–including some ads disguised as news, journalists say.

The state of media freedom in Hong Kong and Taiwan is significant in part because news outlets in both places have in the past provided comprehensive, independent coverage of China, filling a gap left by the tightly restricted mainland press. Any rise in interference, including self-censorship, would imperil the ability of the Hong Kong and Taiwanese press to play a watchdog role.

When Hong Kong returned to Chinese control from British rule in 1997, the territory was granted a high degree of autonomy to manage its domestic affairs under a “one country, two systems” framework. Socialism as practiced by the People’s Republic of China would not be extended to Hong Kong for at least 50 years, and the rights of its residents–including freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly–were to be protected under the Basic Law, worked out between London and Beijing. The Basic Law was to be essentially Hong Kong’s constitution.

Nearly 17 years on, Hong Kong’s media freedom is at a low point. A public opinion survey by the University of Hong Kong in 2013 found that more than half of the public believes the local press practices self-censorship. The United Nations has signaled concern, urging the Hong Kong government in a March 2013 meeting of the U.N. Human Rights Committee to “take vigorous measures to repeal any unreasonable direct or indirect restrictions on freedom of expression, in particular for the media and academia, to take effective steps including investigation of attacks on journalists, and to implement the right of access to information by public bodies.”

According to a survey of journalists by the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) in 2012, the most pervasive problems facing Hong Kong media are self-censorship and a rising number of physical attacks and threats against journalists. Of the survey’s 663 respondents, nearly 40 percent said they or their supervisors had recently played down information unfavorable to China’s central government, advertisers, media owners, or the local government. The HKJA has been tracking censorship trends in Hong Kong since 1968.

[ . . . ]

In Taiwan, journalists say they experience pressure from China in ways both similar and different than their Hong Kong colleagues. Most reporters CPJ interviewed in Taiwan also requested anonymity because of concerns over job security.

As in Hong Kong, most Taiwanese media are backed by individuals who own an array of businesses. News outlets in Taiwan have long been divided along clear political lines. Some are in open support of the Kuomintang (KMT), which favors greater integration with China. Others back the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which is staunchly pro-independence.

Journalists say that media owners on both sides are undermining the country’s freewheeling press in order to protect their expanding business interests on the mainland. Broadcast outlets in particular have come under fire recently as pro-China tycoons have sought to monopolize the airwaves. But unlike in Hong Kong, broadcast media are no longer subject to licensing and programming reviews by the government.

“Like in Hong Kong, the tycoon bosses of Taiwan media are increasingly pushing their media companies to flatter Beijing because they do business with China,” said Chen Hsiao-yi, chairwoman of the Association of Taiwan Journalists and a reporter at the Chinese language Liberty Times for 16 years. “Taiwan media are also becoming more and more reliant on Chinese advertising. They are self-censoring for mostly financial and not political reasons,” she told CPJ.