Media workers in India describe their experiences of how the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi is fostering a political culture that encourages hostility against journalists.

This article was originally published on advox.globalvoices.org on 8 October 2018.

Abuse, intimidation, and attacks on journalists and media organizations are nothing new in India.

In June 2018, veteran journalist and editor-in-chief of Rising Kashmir Shujaat Bukhari was shot dead (along with two police officials assigned for his protection) by gunmen in Srinagar, the north Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir in India.

While the killing evoked public outrage, it failed to change the ground reality for journalists.

Bukhari became the fourth Indian journalist killed this year in connection with his journalistic work, and many more continue to face threats from both state and non-state actors.

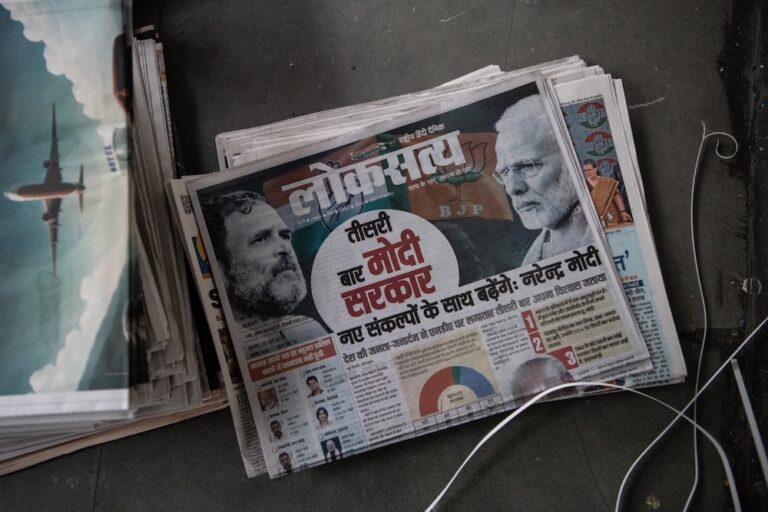

In their 2018 country report for India, Reporters Without Borders notes that the right-wing Hindu nationalism promoted by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, poses a deadly threat to press freedom in India. The report states that there is growing self-censorship among the mainstream Indian media “with Hindu nationalists trying to purge all manifestations of ‘anti-national’ thought from the national debate.”

Being a journalist in Modi’s India

The National Convention Against Assault on Journalists was organized by the Committee Against Assault on Journalists (CAAJ) in New Delhi last month and a number of notable Indian journalists were present.

Speaking to the audience at the convention, NDTV journalist Ravish Kumar criticized PM Modi for fostering a political culture that encourages much hatred against media and that has turned India into a “republic of abuse.”

Ravish kumar speaking in National Convention #AgainstAssault on Journalists with @nehadixit123 @waglenikhil @CPJAsia @caajindia pic.twitter.com/H0F4bwiMB9

— Abhishek Srivastava (@abhishekgroo) September 22, 2018

After Modi’s election in 2014, critics of the government were labeled as “Anti-Modi,” later as “Anti-India,” and then as “Anti-National,” Kumar observed. This type of rhetoric appears to have turned a significant sector of society against a few journalists, in turn, isolating them and silencing them into self-censorship.

In May this year, Kumar reported an increase in abusive calls and death threats from fanatic right-wing nationalists. “It is well-organized and has a political sanction,” Kumar said in an interview with The Hindu.

Making his experience a case in point, Kumar emphasized that freelance journalists, women, and those working in rural areas were far more vulnerable to intimidation and obstruction of work, and lacked the support system that journalists in the capital and large cities enjoyed.

First convention of @caajindia threw light on horrible plight of journalists working in remote areas. From Bastar to Kashmir to North east media persons face harassment by criminals and police in connivance with politicians.Let us unite and support our colleagues. #PressFreedom.

— nikhil wagle (@waglenikhil) September 24, 2018

“The onus does not lie on us, it lies on the state to provide a constitutional mechanism to address these kinds of trolling and threats everybody is facing,” said Neha Dixit, an independent investigative journalist, in her remarks at the convention.

Dixit described a political atmosphere that discourages journalists from talking about the rights of the marginalized. The trafficking and indoctrination of the tribal girls of Assam by right-wing Hindu outfit affiliated with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the phenomenon of working-class Muslims being killed in fake encounters on flimsy charges or the misuse of the National Security Act (NSA), are two examples of issues that larger media houses appear unwilling to cover.

Delving further into the broader problems within the press in India, Dixit lamented that there was no single press body in the country dedicated to addressing the challenges faced by journalists – be it intimidation, false court cases, workplace sexual harassment, or matters pertaining to pay and benefits.

Testimonies of journalists from conflict-zones and rural areas

Speaking of the challenges faced by journalists in Jammu and Kashmir for the last 30 years, Jalil Rathor, a well-known journalist who works in the northern state said,

“In a conflict zone journalist finds himself caught between a rock and a hard place, and is accused of taking sides by both state, as well as non-state actors.”

Rathor stressed that curtailment of government advertisements [the main source of revenues for newspapers in Jammu and Kashmir], banning internet services, and summoning journalists for questioning by state police or at the National Investigating Agency (NAI) in New Delhi, were some of the common ways the government and its agencies continued to intimidate local journalists.

“There is also an attempt to control the narrative [about Kashmir in news] both in traditional media and social media,” Rathor said.

Patricia Mukhim, the editor of Shillong Times, an English daily in the northeastern state of Meghalaya and a survivor of a petrol bomb attack in April 2018, echoed the same anguish as Rathore, about journalists reporting from conflict zones.

Mukhim suggested that for some minority groups, particularly in northeastern India, indigenous identities or sub-identities are stronger than their national identity. She lamented that this kind of ethnic politics, though different from the political culture propagated by the present government in the capital, was equally constricting for freedom of the press.

“If you take a stand for or against something, then one or other group will seek your head,” Mukhim expressed.

Seema Azad, editor of Dastak Patrika and secretary of People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) Uttar Pradesh, sharply criticized India’s Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), a law increasingly used to gag journalists along with activists. The 1967 law is intended to combat terrorism and has been made more and more stringent in recent years. Multiple lawyers and activists have argued that it has significant potential for misuse, especially for silencing dissent.

“When UAPA, the draconian law, was being used against activists, journalists in this country did not speak up. Now it is being used against the journalists.”, says Seema Azad, editor of Dastak Patrika.#NoMoreAssault #PressFreedom pic.twitter.com/U0Y5dzRGmO

— Committee Against Assault on Journalists (CAAJ) (@caajindia) September 23, 2018

Azad urged that there was the need to widen democratic space to include discourse about various people’s movements in India and reporting on issues the government has strongly discouraged, such as the conflict in Kashmir. Reporting about the human costs of the conflict is often characterized by the Modi government as “anti-National.”

Speaking of the impact of crony capitalism, Azad noted, that as the corporate control in India over the years increased — from media houses to natural resources — such attacks have grown.

Lalit Surjan, the Editor-in-Chief of Deshbandhu and a speaker at the convention said, “Journalism in the past, and even in the present times has been a risky undertaking, so be brave.”