According to the Reporters Without Borders tally, the regions with the largest numbers of journalists killed in connection with their work were Asia (with 24) and the Middle East and North Africa (with 23).

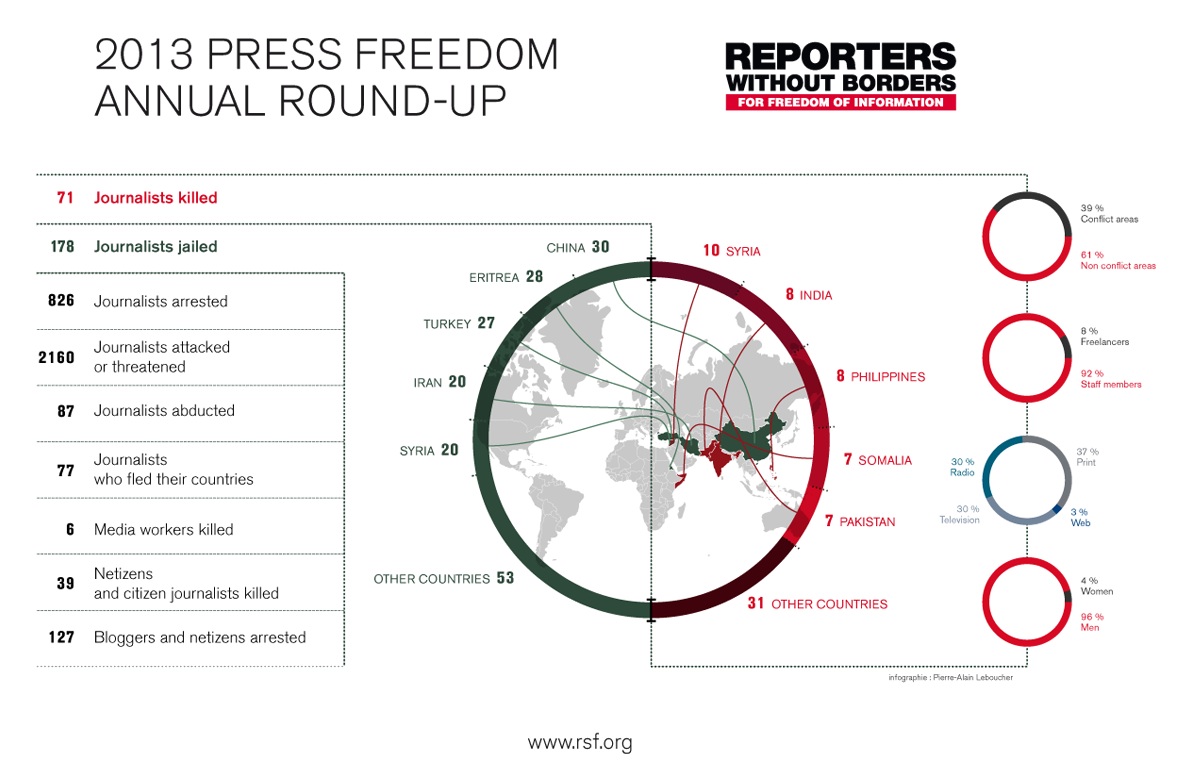

The annual toll of journalists killed in connection with their work was again very high in 2013, although this year’s number, 71, was a slight fall (-20%) on last year’s, according to the latest round-up of freedom of information violations that Reporters Without Borders issues every year.

There was also a big increase (+129%) in abductions and the overall level of violations affecting news providers continued to be very high.

“Combatting impunity must be a priority for the international community, given that we are just days away from the 7th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1738 on the safety of journalists and that there have been new international resolutions on the protection of journalists,” Reporters Without Borders secretary-general Christophe Deloire said.

The regions with the largest numbers of journalists killed in connection with their work were Asia (with 24) and the Middle East and North Africa (with 23). The number of journalists killed in sub-Saharan Africa fell sharply, from 21 in 2012 to 10 in 2013 – due to the fall in the number of deaths in Somalia (from 18 in 2012 to 7 in 2013). Latin America saw a slight fall (from 15 in 2012 to 12 in 2013).

Syria, Somalia and Pakistan retained their position among the world’s five deadliest countries for the media (see below). They were joined this year by India and the Philippines, which replaced Mexico and Brazil, although the number of journalists killed in Brazil, five, was the same as last year. Two journalists were killed in Mexico, while three others disappeared. The return of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) to power and new government pressure on the media contributed to a sharp increase in self-censorship in Mexico. An increase in self-censorship was probably also the reason for the fall in the number of journalists killed in other countries.

39% of the deaths occurred in conflicts zones, defined as Syria, Somalia, Mali, the Indian province of Chhattisgarh, the Pakistani province of Balochistan and the Russian republic of Dagestan. The other journalists were killed in bombings, by armed groups linked to organized crime (including drug trafficking), by Islamist militias, by police or other security forces, or on the orders of corrupt officials.

Of the 71 journalists killed in 2013, 37% worked for the print media, 30% for radio stations, 30% for TV and 3% for news websites. The overwhelming majority of the victims (96%) were men.

The number of journalists killed in connection with their work in 2013 fell by 20% compared with 2012, but 2012 was an “exceptionally deadly” year with a total of 88 killed. The numbers were 67 in 2011, 58 in 2010 and 75 in 2009. The fall in 2013 was also offset by an increase in physical attacks and threats by security forces and non-state actors. Journalists were systematically targeted by the security forces in Turkey, in connection with the Gezi Park protests, and to a lesser extent in Ukraine, in connection with the Independence Square (“Maidan”) protests.

More than 100 cases of harassment and violence against journalists were registered during the “Brazilian spring” protests, most of them blamed on the military police. Colombia and Mexico also saw major protests that gave rise to police violence against media personnel. Journalists were among the victims of the political unrest in Egypt in 2013, sectarian unrest in Iraq, and militia violence in Libya. In Guinea, journalists where regularly threatened, by both government and opposition, during protests prior to the elections. India, Bangladesh and Pakistan also saw an increase in threats and attacks against journalists, as well as murders.

There was a big increase in the number of journalists kidnapped (from 38 in 2012 to 87 in 2013). Most of the cases were in the Middle East and North Africa (71) followed by sub-Saharan Africa (11). In 2013, 49 journalists were kidnapped in Syria and 14 in Libya. Abductions gained pace in Syria in 2013 and became more and more systematic in nature, deterring many reporters from going into the field. Foreign journalists were increasingly targeted by the government and by Islamists groups such as Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) and Jabhat Al-Nosra, but their Syrian colleagues were the most exposed. At least 18 foreign journalists and 22 Syrian news providers are currently abducted or missing.

Threats and violence forced a growing number of journalists to flee abroad. The violence of the conflict in Syria led to the departure of at least 31 professional and citizen-journalists in 2013. Many of them are now in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon or Egypt, destitute and vulnerable. Victims of xenophobia and accused of being Muslim Brotherhood supporters in Egypt, interrogated and threatened by the security services in Jordan, and threatened by pro-Assad militias in Lebanon, their situation often continues to be extremely precarious.

Despite the moderate candidate Hassan Rouhani’s election as Iran’s president in June 2013, and despite his promises of reform, 12 Iranian journalists fled the country in 2013 to escape government persecution.

Five Eritrean journalists fled abroad in 2013 to escape their country’s tyrannical regime, refusing to be President Issaias Afeworki’s propaganda slaves or fearing that they could be arrested and held incommunicado in one of the country’s appalling prison camps.

The exodus of journalists continued in Somalia. Most of them end up in neighbouring Kenya, where their safety and living conditions declined in 2013 because of an increase in xenophobia resulting from the military offensive that Kenya launched in Somalia in 2011 and because of the uncertainty surrounding the UN Refugee Agency’s registration of Somali requests for protection.

At least 178 journalists are in prison right now. China, Eritrea, Turkey, Iran and Syria continue to be world’s five leading jailers of journalists (see below), as they were in 2012. The number of imprisoned journalists is largely unchanged in China, Eritrea, Iran and Syria and has fallen somewhat in Turkey. Legislative reforms in Turkey have led to the conditional release of about 20 journalists but fall far short of what is needed to address the judicial system’s repressive practices.

These violations of freedom of information target news providers in the broadest sense, citizen-journalists and netizens, as well as professional journalists. In addition to the 71 professional media fatalities, 39 citizen-journalists and netizens were killed in 2013 (down slightly from 47 in 2012), above all in Syria. These citizen-journalists are ordinary men and women who act as reporters, photographers and videographers, trying to document their daily lives and the political violence and persecution to which they are exposed.

Reporters Without Borders’ secretary-general called for tougher measures to combat impunity when he spoke at a UN Security Council meeting in New York on 13 December on “Protecting journalists.” RWB wants Article 8 of the International Criminal Court’s statute to be amended so that “deliberate attacks on journalists, media workers and associated personnel” are defined as war crimes.

Additionally, Reporters Without Borders is recommending the creation of a group of independent experts or a monitoring group attached to the UN secretariat with the task of monitoring respect by member states for their obligation to ensure impartial and effective prosecution of cases of violence against journalists. Finally, RWB is calling on the UN and member states to promote procedures for protecting and resettling news providers and human rights defenders who are in danger in transit countries after fleeing abroad, and to create a specific alert mechanism.

To compile these figures, Reporters Without Borders used the detailed information it gathered while monitoring violations of freedom of information throughout the year. Only journalists or netizens killed in connection with the collection and dissemination of news and information were counted in the number of dead. Reporters Without Borders did not include cases of journalists and netizens killed in connection with their political or civil society activism, or for other reasons unrelated to the provision of news and information. Reporters Without Borders continues to investigate deaths in which the evidence so far available has not allowed a clear determination.

The five deadliest countries for journalists

Syria: cemetery for news providers

At least 10 journalists and 35 citizen-journalists killed

Syria’s civil population and news providers continue to be the victims of the Assad regime’s bloody crackdown. News providers are also increasingly being targeted by Islamist armed groups affiliated to Al-Qaeda that do not tolerate news media and tend to regard any news provider as a spy or infidel. In this respect, 2013 was a turning point because Jihadi groups began kidnapping and murdering journalists in the so-called “liberated” zones for the first time since the start of the uprising in 2011. In late 2013, they killed the Syrian journalist Mohammed Saeed and the Iraqi journalist Yasser Faysal Al-Joumaili.

Somalia: Al-Shabaab’s wrath

7 journalists killed

2013 was less bloody than 2012, when 18 journalists were killed, but news providers continue to among the targets of the Islamist militia Al-Shabaab’s bloody activities. Seven journalists were killed in 2013 in attacks blamed on Al-Shabaab, whose deadly methods are notorious. On 27 October, a TV journalist died from gunshot injuries received in a motorcycle attack. In March, a young woman radio producer from the provinces was the victim of an execution-style killing on a Mogadishu street. Such targeted murders sustain a climate of terror in the Somali media community. Journalists are also the victims of a government that fails to protect them and takes a dim view of outspoken independent media. Radio Shabelle‘s journalists were in the habit of living in their offices in order to limit their exposure on the streets until the interior ministry evicted them in October 2013.

India: hate and vilification

8 journalists killed

The toll of eight journalists killed in connection with their work in 2013 broke all records in India. Criminal gangs, demonstrators and political party supporters were to blame in some cases. But local police and security forces were also guilty of rarely-punished violence and threats against reporters, forcing them to censor themselves. The murders of Dainik Ganadoot employees Ranjit Chowdhury, Sujit Bhattacharya and Balaram Ghosh and Dainik Aaj reporter Rakesh Sharma were emblematic of the unprecedented level of violence against media personnel.

All three employees present were stabbed to death by the two men who entered the premises of the Bengali-language Dainik Ganadoot in the northeastern state of Tripura on 19 May. Dainik Aaj’s Rakesh Sharma was deliberately lured into an ambush before being shot in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh on 23 August. Journalists are often targeted by both the security forces and armed rebels in Kashmir and Chhattisgarh. Even if these regions do not have the most victims, they now count among the most dangerous for journalists and are subject to increased censorship by the federal authorities.

Pakistan: bombs and no-go zones

7 journalists killed

With one bombing after another, Pakistan was the world’s deadliest country for the media from 2009 to 2011. Journalists were killed at the rate of almost one a month from 2010 to 2012. Seven lost their lives trying to inform their fellow citizens in 2013. Much of the violence is concentrated in the northwestern Tribal Areas and the southwestern province of Balochistan but these regions do not have a monopoly on violence and impunity.

Karachi is a very dangerous city for journalists, as evidenced by an armed attack on the Express Media building by men on motorcycles on 2 December and the discovery of the body of the Balochi journalist Haji Abdul Razzak on 22 August, months after he disappeared. Police violence, abuse of authority by powerful local officials and anti-terrorism prosecutions continue to jeopardize media freedom. Pakistan has nonetheless been chosen as one of the first countries to implement the UN “Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity.”

Philippines: hit-men on motorcycles

8 journalists killed

What do Rogelio Butalid’s murder in Tagum City on 11 December, and Jesus Tabanao’s murder in Cebu City on 14 September have in common? All were gunned down in cold blood by masked men on motorcycles who did not worry about witnesses. This is such a widespread method that the Philippine Star wrote in an editorial: “The motorcycle has become the getaway vehicle of choice for the murderers of journalists and militants, robbers of banks and armoured vans, and even petty snatchers. Most of the crimes are committed during daytime, when heavy traffic allows crooks on motorcycles to elude pursuing police cars.”

Private militias, corrupt politicians’ thugs and contract killers who work for a few thousand dollars continue to threaten and kill journalists with complete impunity. Eight media personnel were murdered in 2013. Less than 10 per cent of these killings lead to convictions. In the few cases in which the police complete an investigation successfully, the judges are usually unable or unwilling to do their job.

The world’s five biggest prisons for journalists

China: obsessed with surveillance

At least 30 journalists and 70 netizens currently held for providing information

According to official information, around 100 news providers are currently imprisoned in China, but that does not include those held in its notorious unofficial prisons after being abducted. By arresting journalists and bloggers and cracking down harder on cyber-dissidents, the authorities are trying to tighten their grip on news and information and encourage self-censorship. The police above all target human rights defenders and activists campaigning for political reforms such as Xu Zhiyong and Guo Feixiong (Yang Maodong), jailed on trumped-up charges without being brought before a judge.

But journalists and bloggers who embarrass party officials by exposing corruption are also targeted. Liu Hu of the daily Xin Kuai Bao (Modern Express) is the Communist Party’s latest victim, although the party is supposed to be campaigning against corruption within its ranks. Detained since 30 September, he was finally charged with defamation 37 days after his arrest for posting information on his Weibo account about corrupt activities implicating state administration deputy director for industry and commerce Ma Zhengqi.

Eritrea: consigned to oblivion

28 journalists in prison

Hell and damnation are eternal for the 28 journalists currently imprisoned in Eritrea. Of the 11 journalists arrested in 2001, seven have died in detention from mistreatment or despair, in silence and oblivion, and the other four are still held 12 years later, without ever having seen a judge. Prison conditions are inhuman – solitary confinement in underground cells, confinement in metal containers left in the sun for hours, food and water deprivation, and overcrowding.

Only the government has the right to use its voice in Eritrea, which has one of the planet’s last totalitarian regimes and is ranked last in the Reporters Without Borders press freedom index for the eighth year running. Opposition parties, privately-owned media and unregistered religious organization are all banned. Journalists who are suspected of “violating national security” or just being critical of the regime are arrested and left to die a slow death in one of the country’s prison camps.

Turkey: journalists presumed guilty

At least 27 journalists and two media assistants held in connection with their work

Timid legislative reforms and the start of historic negotiations with the Kurdish rebels have so far changed nothing. Turkey continues to be one of the world’s biggest prisons for journalists. This is paradoxical in a country with democratic institutions and an enduring, pluralist press. But the security-obsessed, paranoid judicial system still shows little respect for freedom of information and the right to due process. Supported by an arsenal of repressive laws, the courts are quick to treat outspoken journalists as “terrorists.” Suspects often spend years in preventive detention before being tried. Of the roughly 60 media workers currently imprisoned, at least 29, including Turabi Kisin and Merdan Yanardag, are being held in connection with their work of gathering and disseminating news and information. Many other cases are still being investigated.

Iran: awaiting reform

20 journalists and 51 netizens imprisoned

Hassan Rouhani, a moderate conservative candidate backed by the reformists, was elected president with 51 per cent of the votes on 15 June. Despite his promises of reform and despite the release of some prisoners of conscience, including a few journalists and netizens, most of the news providers who were in prison before his election – the majority of them arrested in the wake of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s disputed reelection as president in June 2009 – are still there.

At least 76 journalists have been arrested since the start of 2013, 42 of them since June. Seventeen others have been given sentences ranging from one to nine years in prison. Twelve newspapers and magazines have been suspended or forced to stop publishing under pressure from the authorities. Inhuman treatment of prisoners of opinion continues to be common. Many detainees are still denied medical care despite being very ill or in poor physical and mental health as a result of their imprisonment.

Syria: news providers held by both sides

20 journalists jailed (as well as 20 other news providers and at least 18 foreign journalists and 22 Syrian news providers kidnapped or missing)

The pace of arrests by government security forces has let up, but more than 40 news providers are still languishing in the regime’s jails, putting Syria among the world’s five biggest prisons for news providers. At the same time, the number of abductions of foreign and Syrian journalists has risen in the so-called “liberated” areas since the spring and the increase in ISIS’s influence in the north. The kidnappings have become almost systematic since the autumn.

CPJ also released detailed statistics today. Information can be found on CPJ’s website.

“Combatting impunity must be a priority for the international community”

Reporters Without Borders