No investigation. No punishment. In Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Pakistan, impunity is the norm. And in neighbouring Afghanistan, the government's vow to address journalists' safety is still to be tested.

Journalists across Asia face real challenges when it comes to dealing with impunity. Investigation of crimes against journalists is rare, and punishment even less likely. We look at the situation in four of the region’s countries: Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and how citizens there are responding.

Sri Lanka: Missing cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda is one among many

On 24 January 2010, Sri Lankan columnist and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda was on his way home from work when he disappeared. The incident occurred two days before the country’s presidential elections. Eknaligoda had been threatened for his political analyses and was well known for his cartoons critical of the administration of President Mahinda Rajakapsa. These were published in the Lanka-e-News, a pro-opposition website that has repeatedly come under attack.

Right after he went missing, the journalist’s wife, Sandhya, began a campaign prodding authorities to seriously investigate his whereabouts. Nevertheless, the case remains unsolved. As such, Prageeth’s case is one of 10 emblematic cases around the globe Paris-based group Reporters Without Borders (RWB) highlighted in its #FightImpunity campaign.

No investigations, no justice

According to Sri Lankan organisation Free Media Movement (FMM), at least 43 journalists and media workers were killed or disappeared in Sri Lanka within the last nine years. No perpetrators have been brought to justice. In its November 2014 campaign, FMM highlighted 10 stories of impunity (Prageeth’s case being among them) and called on the government to bring the perpetrators to justice and establish media freedom in the country.

Cambodia: Lack of accountability for violence against protesters

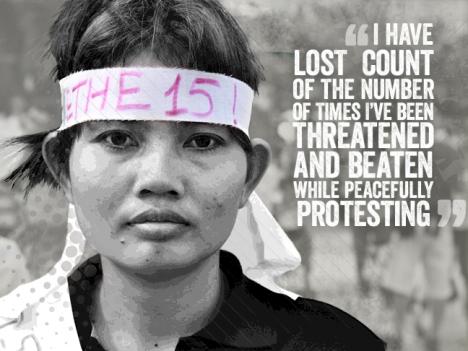

Recent violence against protesters and a failure to hold perpetrators accountable is one of the most significant forms of impunity currently challenging Cambodia, says the Phnom Penh-based Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR).

Cambodian citizens often come out on the streets to demand their democratic rights: In 2013 they gathered to express support for the opposition party and to question the results of the July 2013 National Elections; monks joined ranks with garment workers to protest labour conditions and low wages; and other citizens, such as the members of the Boeng Kak Lake community, assembled to fight for their land rights. CCHR laments a January 2014 ban on assemblies and the excessive, disproportionate use of force by security personnel against protesters that has led to injuries and even deaths. While some protesters have been arrested and even charged for their actions in the protests, there have been no independent or impartial investigations into the violent actions of the security forces.

By cracking down on the right to free assembly, authorities are attempting to shut down one of the main avenues for voices critical of those in power. And it isn’t just the protesters who are risk – In a related attack on media freedom, reporter Lay Samean suffered serious injuries after being targeted for attempting to take photos of security guards chasing a monk during a May 2014 rally.

A culture of fear

“I will not be intimidated . . . I will continue to report the truth,” Samean said after the incident, reports the Cambodian Center for Independent Media (CCIM). The courage behind these words is undeniable. But when such abuses are not addressed, a culture of fear is created which is likely to stop others from speaking out. In Cambodia, well-connected officials often evade justice, while human rights activists and journalists come under attack for shedding light on environmental issues or anything that goes against elite interests; their murders are rarely investigated.

Throughout November, as part of its annual campaign to end impunity, CCHR collected photos of individuals holding signs pledging to fight impunity. The 263 collected photos were made into a giant poster which was delivered to the Ministry of Justice on 2 December, calling for action over high-profile individuals escaping prosecution for crimes.

Afghanistan: Women journalists weigh risks

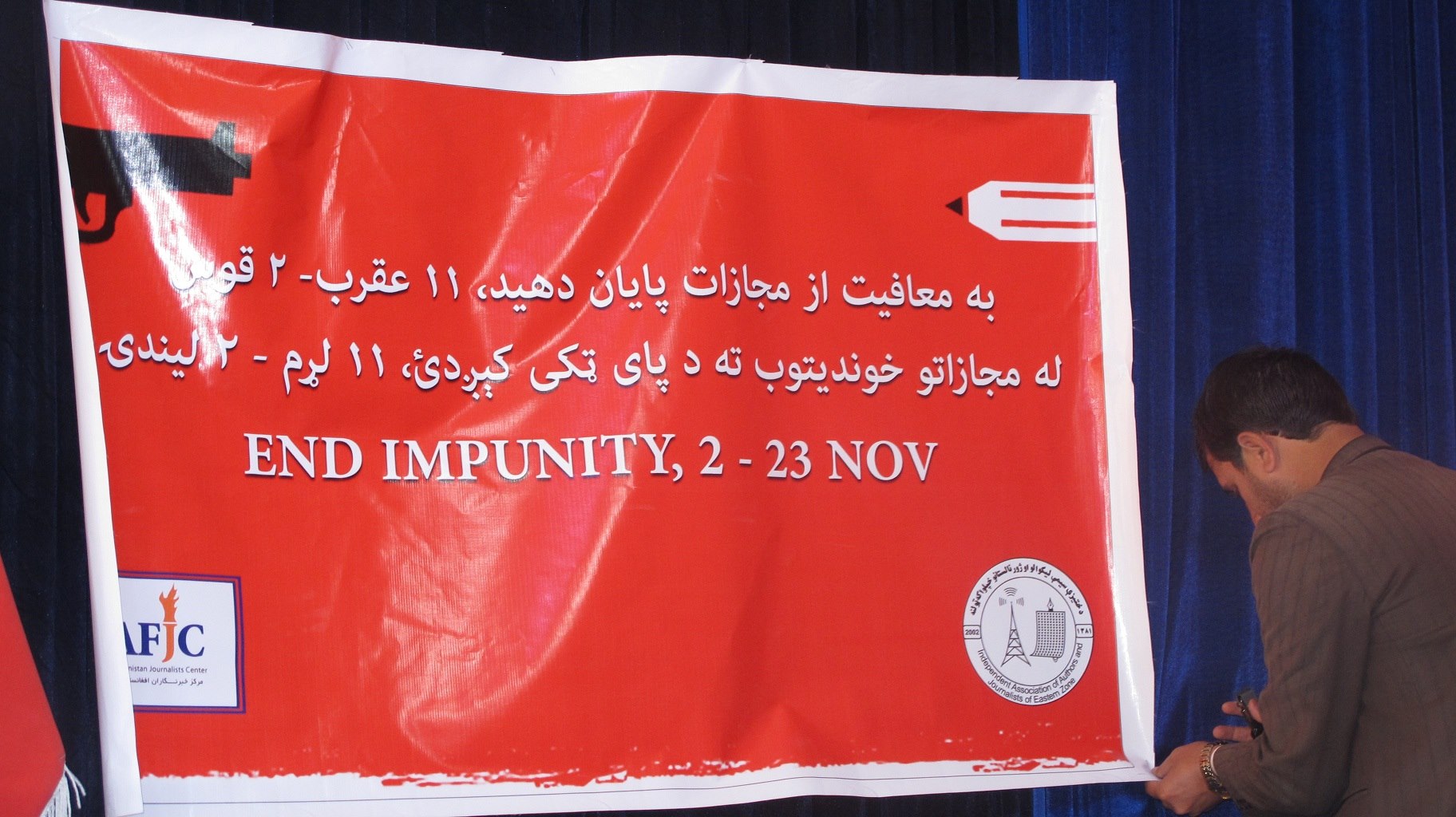

This year, in another part of the region, the Afghanistan Journalists Center (AFJC) carried out its own campaign against impunity in 10 cities across Afghanistan – from 2 November, the inaugural UN International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, to 23 November, the anniversary of the 2009 Ampatuan Massacre in the Philippines, the deadliest attack on the press.

AFJC’s campaign web page highlights the unpunished cases of murdered journalists going as far back as 1994 – foreign and local. Two female journalists are among those killed in 2014: German AP photographer Anja Niedringhaus and 26-year-old Afghan journalist Palwasha Tohkhi Meranzai. Tohkhi had received a death threat relating to her reporting about a month before her murder. Despite evidence that the motive was tied to her profession, Afghan security services persist in treating it as a robbery.

In an interview with the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in Kabul in July 2013, Shaffiqa Habibi, director of the Afghan Women Journalist Union, estimated that of 2,300 women journalists, about 300 had stopped working recently because of concerns for their personal security. Pressure comes from militants, religious extremists, even family members.

Small steps forward

On the heels of the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan, there is uncertainty about the future of a free press and the safety of journalists working in the country. However, there is room for optimism. In August, 20 female journalists in the northern province of Jawjzan formed the first union of female journalists. And on 22 November, Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, the Chief Executive Officer of Afghanistan’s National Unity Government, vowed to put an end to impunity for crimes against journalists and media workers. In a meeting with senior members from AFJC and other media support organizations, Dr. Abdullah assured them of the government’s intent to take “essential actions”. It remains to be seen what these actions will be, but this announcement, on the heels of campaigning by AFJC and other journalists’ groups, was a welcome one.

Pakistan: A conviction in the case of Wali Khan Babar

Pakistan is considered one of the most dangerous countries for journalists. It ranks ninth-worst on CPJ’s Global Impunity Index. Around 113 journalists have died in Pakistan over the last 14 years, according to local digital rights organisation Bytes for All. In only two cases have investigations been completed and convictions carried out: in the 2002 abduction and murder of American journalist and Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl (as a result of pressure by the US government) and more recently in the 2011 murder of Pakistani journalist Wali Khan Babar (where pressure was exerted by the Geo/Jang group, the largest media group in Pakistan and the journalist’s employer).

While the conviction in the Babar case has been hailed as an important milestone, the process was not easy, says Sadaf Khan, Bytes for All program manager on digital rights and free expression. The investigative officer and multiple witnesses were murdered before the investigations were over. Unfortunately the conviction has not encouraged other targeted journalists’ families to pursue their own cases again, Khan adds; nor has it been covered by the rest of the Pakistani media as an important step forward.

Sustained follow up and media coverage of a journalist’s murder is rare, says Owais Ali, executive director of the Pakistan Press Foundation. In most cases media houses lose interest in the story after the initial flurry and industry associations do not follow up the cases with the seriousness they deserve. The Pearl and Babar convictions show that positive results can be achieved in the fight against impunity, Ali notes, but only if media houses take on the responsibility of pursuing the murders of their employees until those responsible are convicted and held to account.

Will the UN Plan of Action prompt change?

The scale and number of attacks on journalists and media workers around the world, combined with the failure to investigate and prosecute these crimes, means that those in this profession face an unacceptably high risk simply for doing their jobs. In response, the United Nations has developed an approach called the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity. In its initial phase, the plan will be mainly implemented in Iraq, Nepal, Pakistan and South Sudan.

In Pakistan, stakeholders have come together under the platform PCOMS (Pakistan Coalition on Media Safety) to agree upon a unified plan of action. Khan of Bytes for All describes some of the benefits of the UN plan for Pakistani civil society: “It has provided us with a framework to create a baseline gauging the extent of journalist threats and to identify stakeholders and possible ways of their intervention. Most importantly, it has given a legitimacy to the efforts of civil society organisations and made the government accountable on this issue.”

Activist and Boeng Kak lake community member Yorm Bophawww.daytoendimpunity.org

Executive Director Chak Sopheap and CCHR staff deliver the poster to the Ministry of Justice, Phnom Penh, 2 December 2014CCHR

AFJC campaign against impunity, 2-23 November 2014AFJC

Bytes for All candlelight vigil in solidarity with the IFEX End Impunity campaign, and the TakeBackTheTech campaign, 26 November 2014Bytes for all

Marianna Tzabiras is the IFEX Section Editor for Asia & Pacific and Digital Rights.