Veteran independent journalist Bheki Makhubu spent over fifteen months in a high security prison in Swaziland for exposing a judicial system that is deeply corrupt - the latest in a string of trials he has endured over the past two decades.

In a Mail & Guardian article published in April 2014, Bheki Makhubu reflects on the importance of free speech: "I wrote an article I believed was of national interest, and because I like to think I understand constitutional law, I believe free speech means we can participate in matters of national importance that touch upon us as a people."

Veteran independent journalist Bheki Makhubu spent over fifteen months in a high security prison in Swaziland for exposing a judicial system that is deeply corrupt – the latest in a string of trials he has endured over the past two decades.

This has not deterred him from continuing to speak out and holding power to account: “I think by nature of human existence, people in authority need to be monitored and called to account, because otherwise, they tend to forget why they are there and sometimes they are not aware of what they are supposed to do; we need to remind them of their functions.”

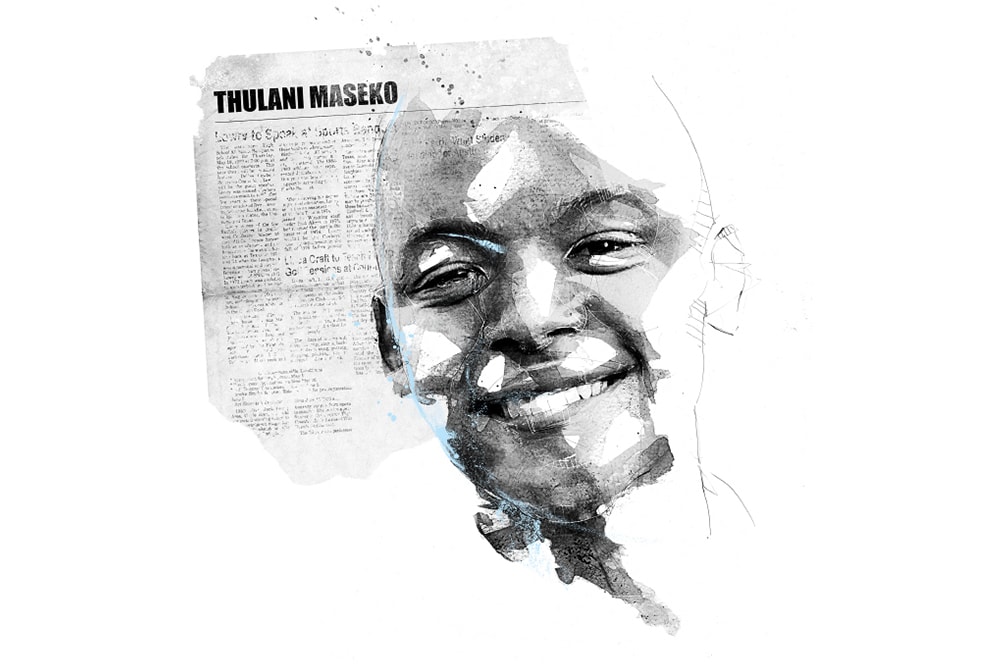

Makhbubu, who was arrested with human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko on 18 March 2014, spent 20 days in custody before being released, only to find himself back in prison three days later, where the two men were to remain until June 2015.

Their crime was to have written articles published in The Nation magazine in February 2014 that questioned the judiciary over the arrest of a government vehicle inspector who had apprehended the car in which a high court judge was travelling.

Upon finding that the driver did not have authorisation for use of a government vehicle, the inspector served the high court judge with a traffic violation ticket. For being conscientious and doing his job properly, the inspector found himself charged with contempt.

Makhubu and Maseko, incensed by this, wrote the presiding judge, Chief Justice Michael Rambodibedi, and accused him of abusing his authority in handling the case. Rambodibedi turned on them, saying that as the inspector’s trial was still under way, they were in contempt of court. He ordered their immediate arrest.

Judged a “flight risk”, the two were denied bail and thrown into a maximum-security prison, usually reserved for hardened criminals. Twenty days later, they were freed on appeal when it was ruled that Rambodibedi had no power to issue an arrest warrant. The judge himself appealed, won the case, and the two men were sent back to jail.

In July 2014, both men were sentenced to two years in prison. They were released on 30 June 2015 after it was decided not to oppose their appeal against their imprisonment. The judge who had presided over their case had since been charged with corruption, undermining any confidence in his capacity to oversee justice. Welcoming the decision, the Southern Africa Litigation Centre described the Swazi judicial system as being applied “at the whim of individuals”, a situation that in 2013 had led to a three-month lawyers’ strike.

Asides from the injustice of the charges, Makhubu was treated as though he was a dangerous criminal, way beyond the severity of the unjust accusation. He describes how just before his arrest, armed police stormed his parents’ and aunts’ homesteads, demanding to know his whereabouts. In court, he was forced to wear leg-irons. En route to the courtroom, he was accompanied by vanloads of armed police. Commentators believe that Rambodibedi – who had been criticised in print by Makhubu previously – bore a grudge against the journalist, and seized the opportunity to ensure maximum punishment.

Swaziland’s record on freedom of expression is poor, and Makhubu has a long history of dissent. In 2013, The Nation had been fined for articles criticising the lack of judicial independence. Further back, since the mid-1990s, IFEX members have stood up in his support: In 1996 he was forced to apologise for an article in Times Sunday of which he was editor, that criticised King Mswati for amassing wealth and ignoring poverty; in 1999 he was sacked from the post because of his criticism of the monarch, and charged with defamation of the King’s fiancé. In 2001, The Nation, for which Makhubu was now editor, was temporarily banned for not fulfilling stringent media law requirements. In 2007 he was fined for defamation for claiming an MP was engaged in corrupt business deals. In 2010 he was on trial again for contempt of court and defamation of the then Chief Justice. With such a history of challenging wrongdoing wherever he sees, it seems unlikely that Mhakubu’s long spell in prison will see him subdued in future.

Illustration by Florian Nicolle