The once-forgotten keyboard symbol is changing our cultural landscape, playing a major role in significant historical events and featuring prominently in the world of campaigning and free speech

The birth of an icon

The social media hashtag was born in August 2007, first proposed by user Chris Messina as a way to organise Twitter content for “groups”.

Eight years on and the hashtag is ubiquitous in our culture. Hashtags are scattered liberally over tweets and a glance at trending topics on any day demonstrates how entwined they are in modern culture’s lexicon. Originally considered confusing by non-Twitter users, a geeky in-joke with no immediate value, they have gradually seeped into the wider world. It’s now commonplace to see hashtags on adverts and mainstream programmes; they have even been adopted (with arguably less success) by the social media giant Facebook.

But away from the world of broadcast hashtags such as #xfactor, hopelessly generic ones like #business or ironic, I-am-commenting-on-my-own-tweet, hashtags such as #justsaying, there is another more powerful and interesting use for them as a tool to help charities and campaigning groups spread their messages.

The charitable approach

Adrian Cockle, digital innovation manager at WWF International, is clear that hashtags are an important mechanism to help the charity build momentum for its campaigns. However, using hashtags effectively for campaigning is not straightforward. He explains that as a global organisation, at any one time it will have several “high priority initiatives and hundreds of other projects sitting underneath them”. The challenge of course is to capture people’s attention, grab their buy-in and get them to use and share the hashtag. In this way the hashtag and its associated message, spreads its tentacles through the network.

One particularly successful WWF campaign called for the Thai prime minister to make the trade in ivory illegal in the country: “a very clear task”, as Cockle calls it. The campaign launched in August 2012 with the agreed tagline and hashtag #killthetrade. Six months later, WWF was able to claim a victory as the prime minister was photographed accepting a petition from WWF of more than half a million signatures as part of her announcement on a ban on the sale of ivory products in the country. The perfect case study then to demonstrate the power of hashtags to affect change? Maybe, although it is important to acknowledge that with this campaign, as is so often the case, hashtags were only one part of a much larger programme of activity.

In the case of #killthetrade, the hashtag was a bespoke one created by WWF; some advice suggests that campaigners should try to piggyback on existing generic hashtags. WWF uses a host of these that relate to the environment and climate change. However, Cockle is clear that this is usually an ineffective approach: “It’s difficult because generally the space we’re in and the kind of hashtags we’re monitoring get so many people using them that actually doing anything meaningful with them, well it’s like drinking from a firehose.”

The power and challenge of free speech

Of course, while charities may plan and execute hashtag campaigns in a structured way, the more high profile campaigning hashtags are often ones that occur organically. In December 2010, a street vendor in Tunisa immolated himself in protest against his treatment by the authorities. According to those who knew him he had been a target for local police officers for years; they frequently confiscated his wares and harassed him.

His self-immolation was not immediately covered by the mainstream media but local Twitter users, outraged at what had happened, started a Twitter campaign using the hashtag #sidibouzid (the area where the incident had happened). It quickly spread online and helped to fuel angry riots across the country that ultimately led to the defection of the Tunisian prime minster. This is generally agreed to be the start of a wave of protest across the Middle East and North Africa, which went on to become known as the Arab Spring.

Subsequent analysis of the hashtag #sidibouzid, by data scientist Gilad Lotan, showed: ”At the end of the cycle, total tweets mentioning Tunisia were more than 196,000. Total tweets mentioning #sidibouzid …were more than 103,000.” A few weeks later in January 2011, activists employed the hashtag #Jan25 to promote the mass demonstration that launched the Tahrir Square revolt.

Although Twitter is by no means the only online platform to help protesters mobilise a group – in the Egypt uprising Facebook was also used extensively – it is in many ways a more suitable platform for campaigning. It is intrinsically more open and public than Facebook; it is also harder to silence. In the aftermath of the January 25 protest, Egypt blocked both Facebook and Twitter. However, by 31 January, Twitter developers, in conjunction with engineers from Google and a voice recognition tool called SayNow, released Speak2Tweet, which allowed anyone to call an international number and leave a message that would then be converted into a tweet.

In the official announcement, Google said: “We hope that this will go some way to helping people in Egypt stay connected at this very difficult time.”

As a company Twitter has always been a fiercely proud of the way its platform supports free speech. It is a topic on which it has publicly stated its position. But its hands-off approach when it comes to free speech was tested in early 2013 when the French government took Twitter to task for failing to remove tweets containing hashtags it said contravened French laws on hate speech. It was a difficult issue that revealed a clash between not only two legal systems, French and American, but a more difficult and nuanced issue about free speech.

Ultimately Twitter agreed to the demands of French authorities and handed over information necessary to help French police identify those behind the tweets. But it was not viewed favourably by many in the US media, with some American lawyers arguing that Twitter should have fought the French government harder.

RT to show your support

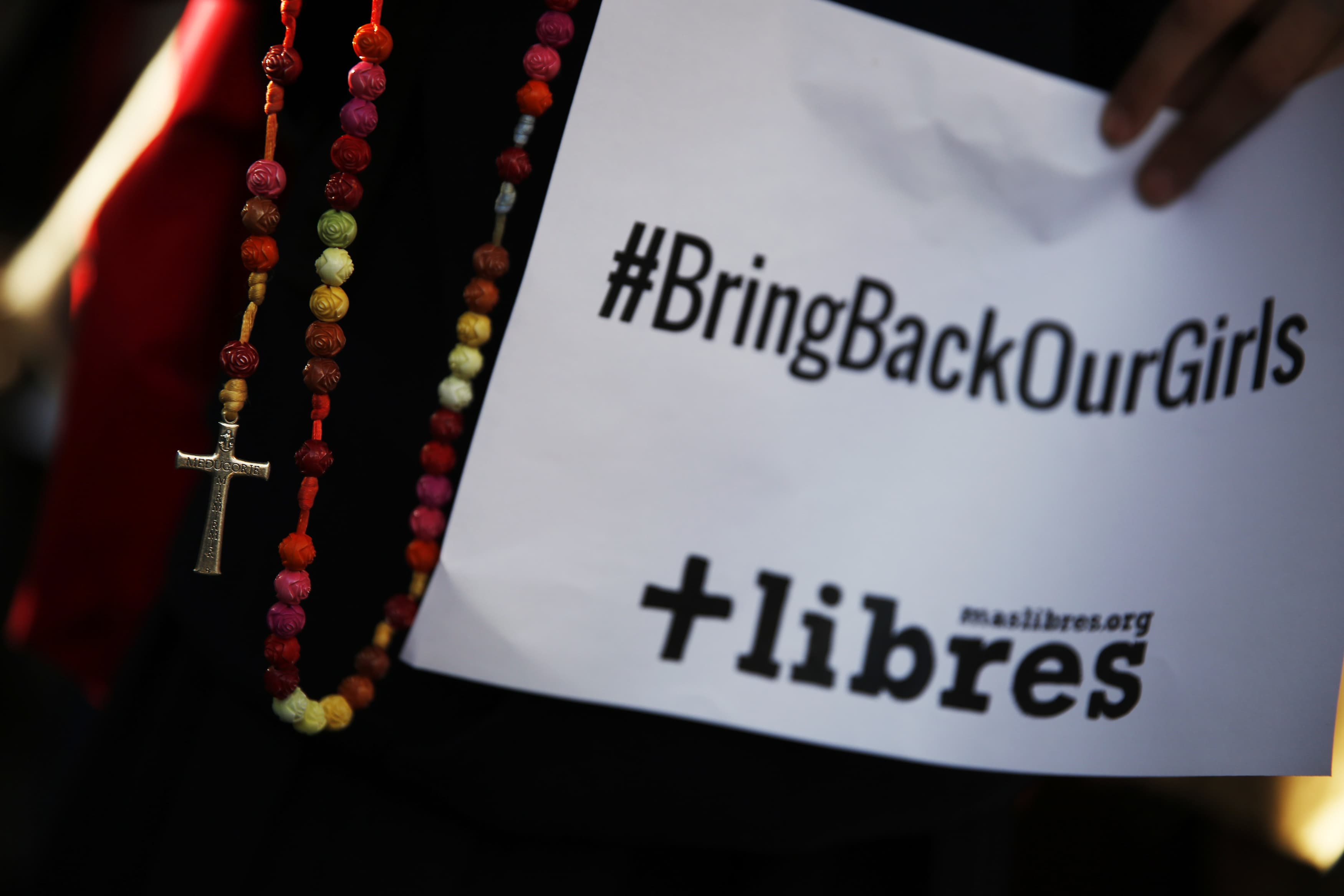

Periodically a hashtag will flood Twitter and generate a huge wave of public support. In April 2014, the kidnapping of 270 girls in Nigeria resulted in one of the most high profile hashtag campaigns to date; #bringbackourgirls was used by thousands of Twitter users, including high profile celebrities, influential leaders and politicians. It was subsequently criticised for being an example of the type of hashtag that encourages armchair campaigning, sometimes termed “slactivism” or “clicktivism”. It’s an easy point to make – what really was the point of all those RTed hashtags when the girls remain captive? But other commentators argue that this conclusion is too simplistic and misses a wider, more important point about the value of #bringbackourgirls.

As Chitra Nagarajan argues in this piece for The Guardian: “The indefatigable Bring Back Our Girls movement continues to hold protests… This campaigning has been successful in highlighting the plight of the abducted girls, and although it hasn’t led to their safe return yet, it has had an important effect on Nigerian politics. Perceived government inaction in the wake of Chibok abductions was not the only reason Nigerians voted Goodluck Jonathan out of office last month, but insecurity and violence in the north-east was one of the main factors in prompting many to vote for change.

“The Bring Back Our Girls movement was instrumental in mobilising the country in protests and conversations about the abductions and, in doing so, helped remove a Nigerian president from power in what will be the first democratic transition in the country’s history.”

Building a community

The notion that a hashtag campaign need not have one fixed outcome to be deemed a success, is one echoed by Katherine Sladden, director of campaigns at Change.org, “Campaigns like Bring Back Our Girls help to disrupt and raise awareness of an issue, they can help to bring about change rather than always being the absolute catalyst for that change,” she says. She points to the fact that as a result of the #bringbackourgirls campaign, political leaders at the World Economic Forum were bombarded with questions about it, bringing it from the original grassroots campaigners in Nigeria to the heart of the international political power brokers.

Sladden is also clear that often the benefits of hashtag and online campaigns aren’t only in the immediate results of those campaigns, but in the way the act of campaigning helps to draw together a group of like-minded individuals. “Most normal people don’t have newspaper columns, or TV shows, or places to express their opinions. Twitter and online campaigning is an easy way to organise around a shared belief. That’s how it should be. It’s about building communities so people feel supported in their campaign or issue.”

At Change.org hundreds of campaigns are launched every day that deal with all sizes of issue, from the hugely ambitious to the modestly hyperlocal. Sladden sees commonalities between the campaigns that gain traction and they aren’t to do with any existing influence of the individual behind the campaign.

“The campaigns that stand out and become popular usually have two things in common. Firstly, they have a personal story behind them; this helps people to feel a personal connection to a campaign. Secondly, the campaign usually has a clear ask, so with Caroline Criado-Perez’s banknote campaign, the hashtag #womanonabanknote, while tackling a big issue, had at its heart a very simple desired outcome.”

Whatever the criticism levelled at clicktivism, there is no doubt that hashtags are having a significant impact on our cultural landscape. Less than ten years, ago this small symbol would be meaningless to many and yet now it plays a major role in significant historical events and helps campaigners from a huge variety of backgrounds to mobilise support. Perhaps most interesting is how it morphs and adapts itself to become a different tool in different situations. It is clear that, at least for the near future, the hashtag will continue to feature prominently in the world of campaigning and free speech.

Katie Moffatt is a digital engagement specialist, trainer and writer based in the UK.