A series of news reports on government corruption is followed by a surprising notice, delivered by motorcycle couriers, informing opposition newspaper employees that they no longer have a workplace.

Last weekend, employees of Népszabadság were preparing to move back into their newly renovated offices. They had packed up their computers on 7 October 2016, and were promised a celebration – with pizza – in their new workspace on 9 October.

Instead, on the day before they were to move back in, motorcycle couriers came to their homes with some news: Népszabadság had been shut down. The journalists would continue to receive their salaries, but they were no longer allowed to do their jobs. Employees were not permitted to enter their office building; access to e-mail and editorial platforms had been revoked; and their website, nol.hu, had also been shut down.

Népszabadság’s publishers, Mediaworks, attribute the closure purely to finances, claiming that the paper was generating “a considerable net loss” in 2016 and that over the last 10 years, circulation had dropped by 74 percent. On 10 October, Népszabadság’s editor-in-chief, András Murányi, said the paper would be sold.

But opposition critics and members of independent media suspect the motives are about far more than money.

“The way it was done raises reasons for concerns – without transparency, without due process,” Dunja Mijatovic, media freedom representative for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, told The Associated Press. “It’s hard to believe this is just a simple business move. All this to me looks like something that’s definitely further damaging media freedom in Hungary.”

IFEX member the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) says that the decision to close Népszabadság immediately follows its publication of articles on corruption scandals, including one about the Central Bank Governor’s connections to government officials, and a report on minister Antal Rogán’s luxury trips in a private helicopter.

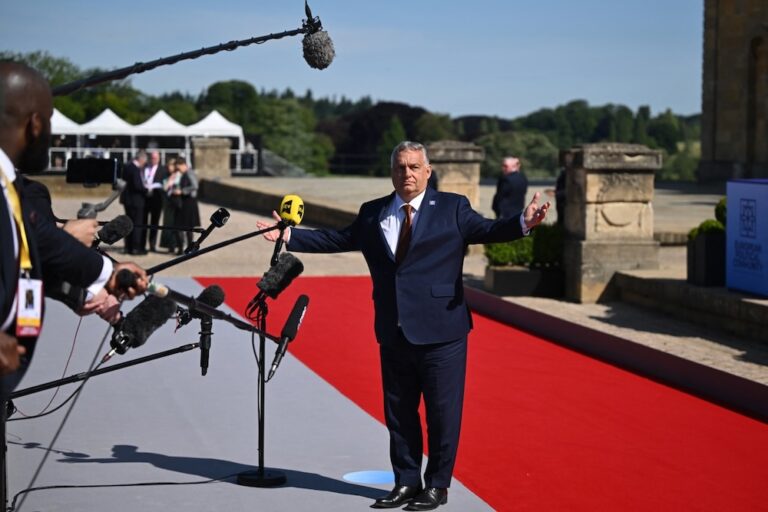

Népszabadság has been just as vocal on other issues related to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s right-wing government, having recently opposed Hungary’s recent referendum on refugees.

Steven M. Ellis, the Director of Advocacy and Communications for the International Press Institute (IPI), says that if the newspaper is sold, it will be “part of a pattern by which business interests closely aligned with Prime Minister Orbán’s Fidesz party have acquired publications in an effort to broaden the government’s control of the Hungarian media.”

If Népszabadság is indeed acquired by business interests close to the government, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has stated that it “would just confirm the prime minister’s growing domination of the Hungarian media.”

On the afternoon of 8 October, approximately 2,000 people attended a rally outside Parliament to protest the closure of Népszabadság. IPI reports that some demonstrators lit a bonfire using copies of the pro-government daily Magyar Idök.

Since Viktor Orbán’s party, Fidesz, came into power in 2010, his allies have purchased numerous print and online publications as well as radio and television stations. According to The New York Times, these platforms have adopted purely pro-government positions.

“If you want to live in democracy you have to pay a price and you need to hear differing, critical voices,” Mijatovic said. “At the moment, those voices are disappearing in Hungary and I think this is extremely dangerous.”

HCLU reports that on Sunday, Népszabadság management invited employee representatives to discuss the closure, but would not allow their attorney to attend, claiming that the presence of the lawyer “would undermine the trust” between the parties.

Employees asserted they would not continue the negotiation without their lawyer.

“It is highly problematic that the journalists of Népszabadság are unable to access their archives, finish their ongoing articles, while the protection of their sources is in danger,” says Dalma Dojcsák, head of the HCLU’s Freedom of Speech Program.

Hungary is rated as “Partly Free” in Freedom House’s Freedom of the Press 2016 report. The country is ranked 67th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2016 World Press Freedom Index, having fallen 48 places in just five years.