For his work as a journalist and political analyst in Iran, Ahmad Zeidabadi has been subjected to arrest, jail, torture, exile, and a lifetime ban from all public and political activity, including journalism.

In his acceptance speech for the International Press Institute's World Press Freedom Hero award in March 2016, Ahmad Zeidabadi describes what it feels like to be banned from his profession for life: Alas! It seems I am condemned to become a stranger in my own country and have my mouth shut. In such a condition, sometimes I think I have been condemned to 'civil execution' or to go through a 'silent death' and be forgotten altogether.

Ahmad Zeidabadi began his career as a journalist in Tehran in 1989 with Iran’s longest-running daily newspaper Ettela’at, shortly after the death of Ayatollah Ruhollah al Khomeini – founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the leader of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. When a reformist politician was appointed Mayor of Tehran that same year and founded Hamshahri, Zeidabadi, a reformist himself, left the conservatively aligned Ettela’at and joined the new daily, a newspaper that later became the most-read in Tehran.

In the years that followed, Zeidabadi built his reputation as a well-known and fearless political analyst in Iran. In 1997, when reformist Mohammad Khatami won a landslide victory in Iran’s presidential elections, an easing of government censorship allowed for a reformist press to flourish and Zeidabadi was at its helm. Unfortunately, hardliners both inside and outside the government moved to crush Khatami’s plans to reform the Iranian system, and their first targets were journalists like Zeidabadi.

In 2000, he was subjected to the first of many violations of his right to freedom of expression. He was arrested for ‘failing to answer a court summons’ and forced to spend seven months in Tehran’s Evin prison, two of which were spent in solitary confinement. Less than two weeks after his release, he was arrested again, this time on charges of ‘conspiring against the government’. He was released again shortly thereafter, when Speaker of Parliament Mehdi Karroubi intervened on his behalf.

In early 2002, he was again put on trial and sentenced to 23 months in prison, later reduced to 13. He was also banned from “all public and social activity, including journalism” for a period of five years. But Zeidabadi was undeterred, and he moved on to providing political analysis on Iran and the region to multiple reformist outlets both online and offline.

Zeidabadi did not waste any time after his writing ban was lifted in 2007. He penned a widely circulated letter – one whose impact would later cause much suffering for him – in which he directly addressed Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khomeini and questioned his lack of tolerance for criticism as well as his handling of the nuclear program and the international community’s response to it.

Two years later, the consequences of that letter and his staunchly reformist stance caught up with him. In 2009, he was one of 100 journalists and pro-reformists who appeared before the judiciary in a televised mass trial after being accused of trying to provoke ‘a velvet revolution’. He was subsequently sentenced to six years in prison and five years of domestic exile upon release. He was also banned from journalism, as well as any other civic or political activity – this time, for life.

After completing his six-year prison term in 2015, Zeidabadi was exiled to Gonabad in the northeastern province of Khorasan. In 2023, he was sentenced again to one year imprisonment and 50 lashes on charges stemming from the 2009 case.

In the same 2016 acceptance speech, he lamented his inability to do what he does best at a time when sound and objective writing is gravely needed in the region.

“It is a great injustice to deprive a human being of doing what gives meaning to his life and what he is specialised in… These days, the Middle East is in turmoil and my country is going through stormy upheavals. Naturally, I am keen to express my expert analysis and warn the people of the bogus news published by some powerful political wings.”

The IPI award has given Zeidabadi hope that he hasn’t been forgotten, and that one day, he might write again.

Not one to forget other political prisoners, Zeidabadi was among twenty who signed an open letter in September 2017 calling on the authorities to respect the demands of 15 political prisoners who went on a mass hunger strike in Rajaee Shahr Prison.

Today, Zeidabadi continues to have a voice online, providing domestic and regional analysis, including on his “Other Perspective” telegram channel.

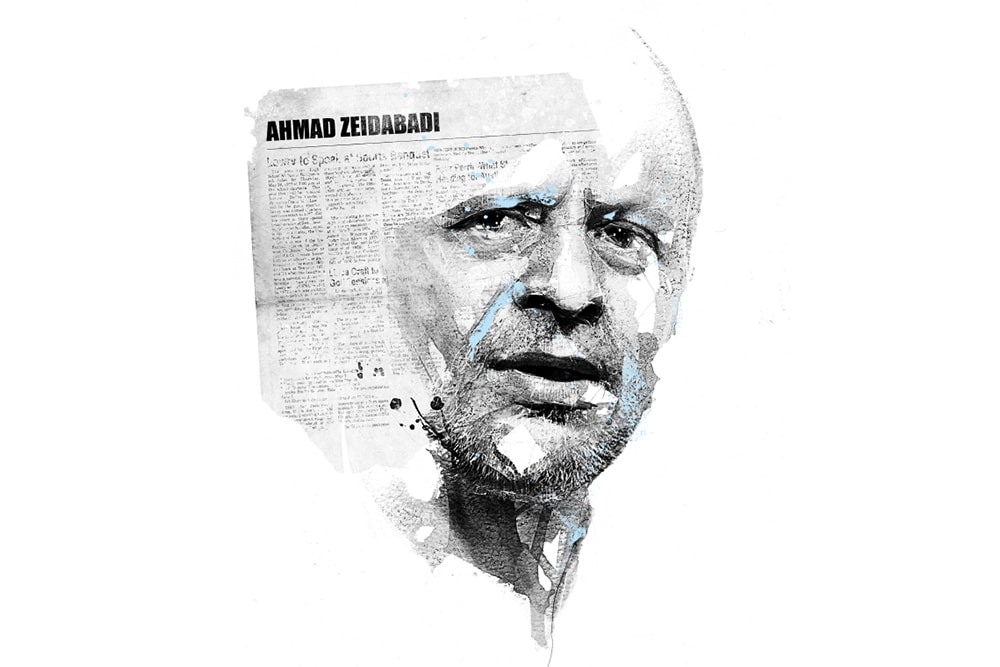

Illustration by Florian Nicolle