Yara Sallam, an Egyptian human rights lawyer and feminist, spent over a year in prison under the draconian protest law - a law that is being used to jail and restrain activists such as her, and which she had been researching when she was arrested.

In a July 2013 blog post, Yara Sallam wrote: What kind of force do we push into a movement if it's based on despair and helplessness? My life, if it can have any meaning at all or if it will be ever remembered, I want it to be about hope, laughter, joy, passion and love for life. My revolution is the same.

Since February 2011, Egypt has seen the pro-democracy movement that forced the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak, then parliamentary elections that brought the Muslim Brotherhood into power and the election as President of its leader, Mohamed Morsi. Morsi was ousted in June 2013 by his former Defence Minister Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and subsequently sentenced to death. Under el-Sisi’s rule, hundreds of his political opponents have been imprisoned and over 700 Morsi supporters given the death penalty. There has been no accountability for the killings of over a 1,000 civilians who protested against his election. There is increasing pressure on NGOs with the introduction of stringent laws that demand that they be registered under strict terms that has led some to close and others to cut back their activities.

Under this cloud, dissent remains strong but it comes at a high price. On 21 June 2014, several hundred people gathered in Cairo for the International Day of Solidarity for Egyptian Detainees, to protest against the Protest Law that gives the government powers to ban demonstrations, providing prison terms of up to five years for people who “call for disrupting public interests”. Demonstrators made their way towards the Ittihadiya Palace that houses the Presidential offices. There they were met with police firing teargas canisters and pro-government thugs who beat them with sticks and glass bottles. Sallam was not among the demonstrators but had been nearby, buying a bottle of water, when she was seized by police and was detained along with 23 others. In October 2014, the group, including Sallam, was sentenced to three years in prison, reduced to two years on appeal in December that year. Lawyers argued that there was no evidence that the defendants had used violence, and to charge Sallam, who had not even been at the demonstration, was doubly unfair. She was among 100 political prisoners freed under a presidential pardon on 21 October 2015 after 15 months in prison.

Sallam ventured into the realm of human rights activism at a young age. As a teenager she was a member of the Al-Nosoor al-Sagheera (The Young Eagles) that brought together young people to discuss and engage in human rights, particularly children’s rights. She went on to study law, gaining two degrees, one from Cairo University and the other from the Sorbonne in Paris, then to obtain a Masters in International Human Rights from Notre Dame University in the USA. When the democracy movement broke out in 2011, she was in Gambia working as a legal assistant at the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights. She returned to Egypt, and threw herself into the democracy movement joining the human rights organisation, Nazra, to set up its Women Human Rights Defenders program. She worked for women who had been arrested, tortured and sexually abused during demonstrations, providing legal help, ensuring their families knew where they were held, making sure they had medical attention and being present at their interrogations. Sallam’s work earned her the Africa Human Rights Defender Award in 2013. In a video marking her award, Sallam says: “I, like you [men], have the right to be in the public space. I have the right to be safe. I have the right to be equal to anyone else. And that my gender is not used against me.”

In 2013, Sallam re-joined the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) for which she had worked some years earlier on discrimination of religious minorities. As its Transitional Justice Officer, Sallam documented restraints and attacks on anti-government protests under the Protest Law until she herself became victim of the same law.

In a blog post published in October of 2017, Sallam wrote a damning report of the death penalty based on her own experience in the military ward where she could hear the screams of women in al-Makhsous (the death penalty ward, makhsous meaning ‘special’). She wrote that “by the time I was released 15 months later, all the women in al-Makhsous had been hanged, and the ward had filled up again. The current president does not love life.”

Continuing her work as a researcher on transitional justice issues at EIPR, Sallam has also become a fierce advocate for mental health issues, writing personal narratives about the topic on her blog, and creating a platform documenting the personal experiences of feminists working in the human rights fields. In 2020, Sallam published Even the Finest of Warriors, featuring a compilation of her writings about the physical and mental strain women human rights defenders face when working in repressive environments throughout the MENA region.

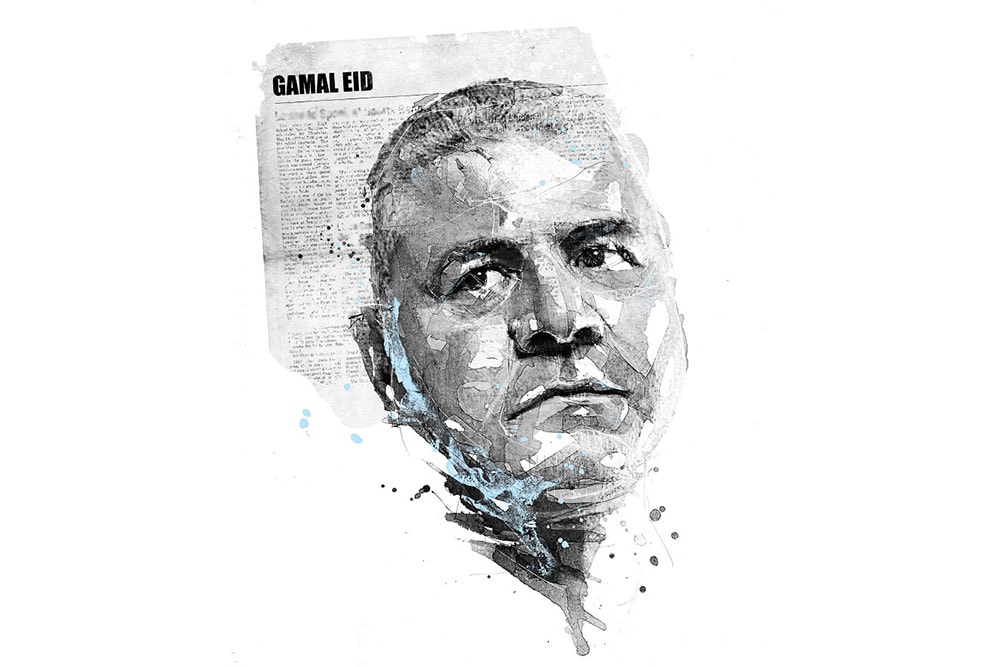

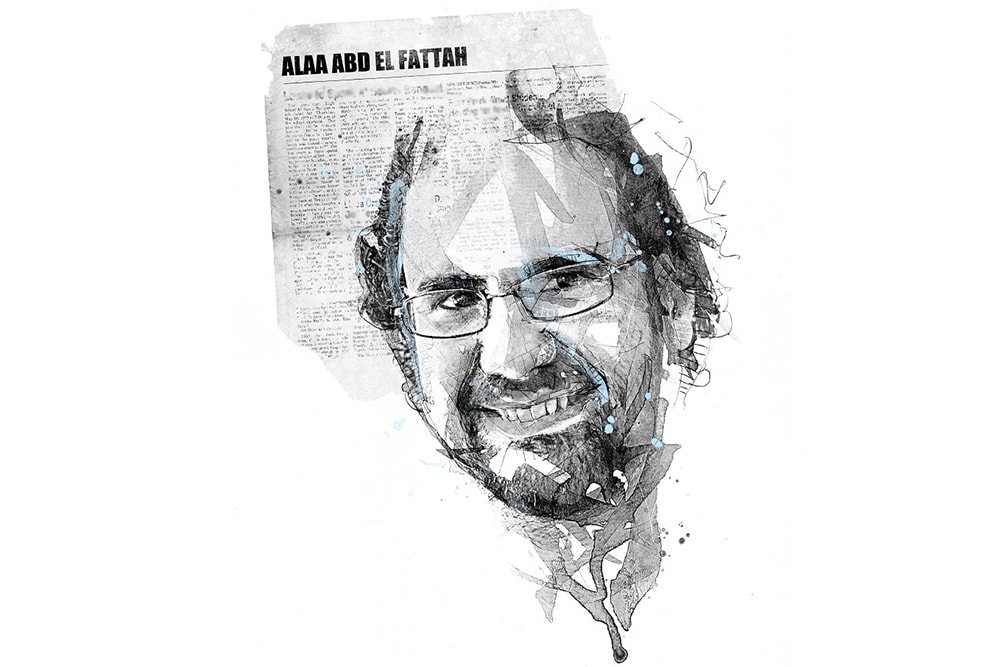

Illustration by Florian Nicolle