Bahrain has spent millions fostering the image of a reformist government. By relentlessly exposing repression and injustices, women's rights activist Ghada Jamsheer has ensured that was not money well spent.

In a Frontline Defenders' case profile of her, Ghada Jamsheer is quoted saying: If the woman does not have safety in her own country, and does not have justice in her country's courts, and does not have justice in her marriage, where will she go? If there are no laws to protect her from abuse, or if there are laws but they are not enforced, where can the woman go?

While the state of women’s civil rights in Bahrain is widely thought to have improved under the reign of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, with women being allowed to vote as of 2002 and to stand as candidates in municipal and parliamentary elections, independent Bahraini women’s rights advocates have refused to accept what they consider nominal and superficial reforms.

Led by outspoken women’s rights advocate Ghada Jamsheer, a network of Bahraini women human rights defenders came together to found the Women’s Petition Committee at about the same time King Hamad began to initiate selected reforms in 2002. Their mission was, and still is, to tackle the issue that leaves Bahraini women – whether allowed to participate in political life or not – most vulnerable: the lack of a codified family law and the ceding of matters related to marriage, separation, parentage and other personal law issues to the control of all-male religious Sharia courts.

“The absence of such a law means that the sharia judge has the final say, he rules on God’s command, what he says is obeyed and his order is binding. You find each sharia judge ruling according to his whim,” said Jamsheer when describing her organisation’s goal. “The demand for the promulgation of this law aims at eliminating many problems and at unifying rulings; it would reassure people of the conduct of litigation, and would guarantee women their rights rather than leaving them at the mercy of fate.”

For over a decade since the WPC’s founding, Jamsheer has been a thorn in the side of King Hamad’s image of a progressive reformist, and she has been punished for it.

Until early 2005, Jamsheer was busy organising protests, vigils and a hunger strike in an effort to draw attention to the suffering of women in Bahrain’s family court system. In 2003, her organisation collected 1,700 signatures on a petition demanding legislative and judicial reform of Sharia courts. Determined to expose the Sharia courts’ often corrupt and unqualified judges, Jamsheer made many media appearances to deliver the fiery speeches she is known for today. She spoke to both local and international leaders in order to bring as much attention to the issue as within her means.

It wasn’t long before the Bahraini government brought criminal charges against her for defaming the Islamic family court. In three separate trials in 2005 she faced up to 15 years in prison. The charges were soon dropped, but starting in 2006, Jamsheer began losing the freedoms and influence she had enjoyed. She was placed under permanent surveillance by the government, and local media outlets were banned from publishing any news relating to her.

That same year, Time magazine identified Jamsheer as one of four heroes of freedom in the Arab world, and Forbes magazine named her one of the ten most powerful and effective women in the region.

Until 2009, two separate Sharia courts existed for Sunni and Shia Muslims in Bahrain. That year, the government approved a family law code for the first time for its Sunni citizens only; Shiites were excluded from the legislation after religious scholars and lawmakers from the community rejected the draft proposal and threatened nationwide protests. Bahrain is a majority-Shiite country so most women remained unprotected by the new law.

Jamsheer and her colleagues continued to advocate for a unified family law that applies to all Bahrain’s citizens equally. As protests rocked the tiny island nation in 2011 and the government responded with a crackdown that has continued to this day, Jamsheer expanded her campaigning to include abuse by government authorities and corruption. It was a series of tweets alleging corruption in the management of King Hamad Hospital in Bahrain that landed her in trouble again with the authorities in 2014.

On 14 September 2014, she was arrested and detained against the backdrop of ten complaints filed against her by different individuals for posting “insulting” and “defamatory” tweets. She spent 10 weeks in detention, was released on 26 November, and re-arrested 12 hours later on accusations of “assaulting a police officer”. She was released yet again on 15 December and placed under house arrest until 15 January 2015. In March, as she was headed for France for medical treatment, Jamsheer was banned from boarding the plane.

Jamsheer received a one-year sentence, suspended for three years. As for charges of insulting the management of a public institution following her criticisms of corruption at King Hamad Hospital, she was sentenced to one year and eight months in prison on appeal. After spending a few weeks in London, England for medical care purposes, Jamsheer was arrested on her way back on 19 August 2016 at Bahrain’s airport in Manama.

Jamsheer was freed on 12 December after spending four months in the Isa Town Women’s Prison. She was required to work off the remainder of her sentence at a government-appointed job.

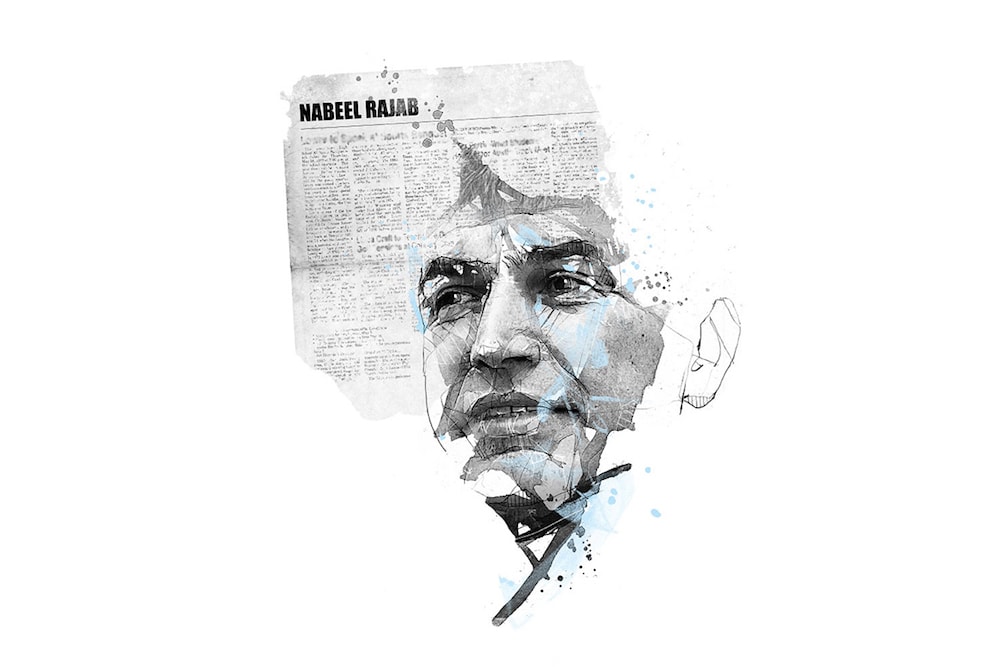

Illustration by Florian Nicolle