A leading human rights lawyer, Thulani Maseko spent over 15 months in prison for criticising Swaziland's corrupt judicial system and the absolute monarchy that gives the king ultimate authority over the cabinet, legislature and judiciary.

In a letter written from prison in March 2015, Thulani Maseko wrote the following: "In spite of the prison hardships, we are not deterred. We are not discouraged. We are not fazed. We are not shaken. We are not intimidated. Yes, we are not broken."

Thulani Maseko’s persistent struggle to stand up to King Mswati’s abuse of power, lack of respect for human rights, and excessive corruption, has pushed him to chip away at human rights violations through the use of strategic litigation. As he once explained: “. . . I think the struggle for human rights is about fighting what is wrong in favour of what is right. And therefore I will continue doing so, until the king and his advisors see the light that there is a better life for all in a democratic society.”

In 2018, he questioned King Mswati’s decision to change the nation’s name from the Kingdom of Swaziland to the Kingdom of eSwatini. In his High Court submission, Maseko argued the King’s unilateral decision, taken without public consultation, “undermined the Constitution and was a waste of money, especially in a country with the world’s highest HIV/AIDS rate.”

The court has yet to rule on the matter.

Described as one of Swaziland’s most vocal upholders of the rule of law, Maseko has challenged the constitutionality of sections of the Suppression of Terrorism Act and the Sedition and Subversive Act.

The case emanated from his arrest in 2009 for sedition for comments he made, during a May Day Workers event, referring to a botched assassination attempt. At the time he was representing Mario Masuku, president of the People’s United Democratic Movement (Pudemo), who was in prison. Maseko and his colleagues Masuku, Maxwell Dlamini and Mlungisi Makhanya, were charged with sedition, subversion, and terrorism for their membership in an opposition movement, wearing t-shirts with party emblems and chanting slogans associated with the movement.

A full bench of the court ruled that sections of the Suppression of Terrorism Act and the Sedition and Subversive Act were unconstitutional and violated freedom of expression and association, and were therefore null and void. The judgement went further, declaring it “unlawful to limit free speech for the sole purpose of shielding the government from criticism or discontent,” according to the Columbia Global Freedom of Expression.

Maseko is no stranger to the cost of fighting for what is right. He was arrested with journalist Bheki Makhubu on 18 March 2014, spent 20 days in custody before being released, only to find himself back in prison three days later, where the two men were to remain until June 2015.

Their crime was to have written articles published in The Nation magazine in February 2014 that questioned the arrest of a government vehicle inspector who had apprehended the car in which a high court judge was travelling.

Upon finding that the driver did not have authorisation for use of a government vehicle, the inspector served the high court judge with a traffic violation ticket. For being conscientious and doing his job properly, the inspector found himself charged with contempt.

The articles accuse Chief Justice Michael Rambodibedi, who presided over the vehicle inspector’s case, of abusing his authority in his handling of the case. Rambodibedi turned on them, saying that as the inspector’s trial was still under way, they were in contempt of court. He ordered their immediate arrest. Judged a ‘flight risk’, the two were denied bail and thrown into a maximum-security prison, usually reserved for hardened criminals.

Twenty days later, they were freed on appeal when it was ruled that Rambodibedi had no power to issue an arrest warrant. The judge himself appealed, won the case, and the two men were sent back to jail.

In July 2014, both men were sentenced to two years in prison. They were released on 30 June 2015 after it was decided not to oppose their appeal against their imprisonment. The judge who had presided over their case had since been charged with corruption, undermining confidence in his capacity to oversee justice. Welcoming the decision, the Southern Africa Litigation Centre described the Swazi judicial system as being applied “at the whim of individuals”, a situation that in 2013 had led to a three-month lawyers’ strike.

The treatment of the two men – being held in a maximum-security prison, treated as Tanele, Maseko’s wife describes ‘as a first class criminal’ – is seen as additional retribution for their long-standing criticism of the judiciary.

However, Maseko could not be silenced in prison. In March 2015, the anniversary of his arrest, he wrote an open letter of “appreciation to the world’s human family for the solidarity of our just cause” in which he speaks of the indignities he and other prisoners suffered while at the same time defiant in his conviction that he and his supporters would not be discouraged: “They shall never conquer our spirits. They may keep us in jail as much as they please, but they can never arrest our ideas.” For this defiance, Maseko was placed in solitary confinement for three weeks.

A year earlier, in August 2014, Maseko wrote an open letter to President Obama asking him to use his influence to encourage world leaders to call for constitutional change that would cement freedoms that are sorely lacking in Swaziland. In it, he refers to his country where the monarch holds absolute power, where political parties are banned and a climate “hostile to the people’s meaningful and effective participation” in decision-making.

Shortly after the publication of the letter, the contents of which were discussed at the United States Africa Leaders Summit, Swazi authorities moved Maseko from Sidwashini Prison in Swaziland’s capital, Mbabane, to Big Bend prison approximately 150 km away. The move was made because Swazi authorities believed officers helped him smuggle the letter out, and the move was meant to break his spirit by distancing him from his family.

Maseko is no stranger to negative government reaction. But as he once wrote while still in prison: “the respect for Rule of Law is not just a theoretical matter; it is a matter of practice.” It is this belief in the rule of law being the only guarantee for democracy, freedom, justice and good governance that pushed him to challenge the anti-terrorism laws of his country.

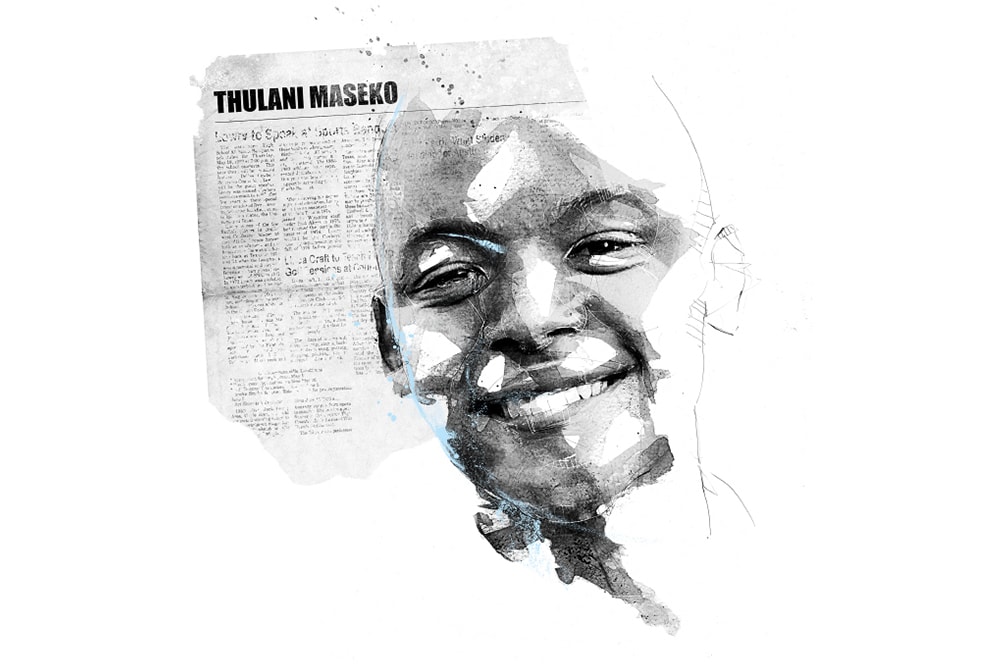

Illustration by Florian Nicolle