One of the few women journalists in Liberia, Mae Azango has taken on the taboo topic of female genital mutilation (FGM). Her tenacity and fearlessness has led a previously reluctant Liberian government to move towards banning the practice.

During the UNESCO World Press Freedom Conference in May 2013, Mae Azango told Internews: Women and girls are the vulnerable group in society. If we women don't talk about what affects women most, men journalists won't. If female journalists keep quiet, those things will keep happening to us.

In her memoir, The Voice of the Trumpetess, published in 2017, Mae Azango speaks of her commitment to telling the stories of ordinary people and their suffering. The celebrated journalist also writes about her own struggles.

One of the few women journalists in Liberia, Azango has taken on the taboo topic of female genital mutilation (FGM), leading to her being threatened and forced into hiding for a time. Yet it is her tenacity and fearlessness that has led to a previously reluctant Liberian government to move towards banning the practice.

In Liberia, where according to World Health Organisation statistics, around 58% of girls have been subjected to FGM, getting at the true extent of the problem is hampered by the secrecy under which this traditional initiation rite is carried out. In March 2012, Azango wrote an article that was to have a dramatic impact. Published in Front Page Africa, “Growing Pains: Sande Tradition of Genital Cutting Threatens Liberian Women’s Health”, pushed aside taboos, describing how “cutting” is carried out, the pain suffered, and the often life-long medical complications that follow. Azango also wrote about how victims were too scared to speak out for fear of being “hunted down” by the secretive Sande women’s society that carries out the procedure at their bush schools where girls are prepared for married life and raising families.

The article led to a furore, inside the country and internationally. The newspaper was inundated with death threats from Sande members as well as from others who felt that this was an issue that should not be spoken about. Azango was forced to flee her home with her 9-year-old daughter, telling the Committee to Protect Journalists at the time that she had been warned “that they will catch me and cut me so that will make me shut up”.

Such is the sensitivity around the subject of FGM that even Liberia’s first female President and joint 2011 winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, had been reluctant to put in place measures that would ban the practice. Yet the outcry following Azango’s report and her forced flight led Liberian officials to announce that the practice should be stopped and Sande-run schools had their licenses withdrawn. In September 2015, at a meeting where over 80 government leaders gathered at the UN in New York to state their commitment to the elimination of gender inequality and violence against women, President Sirleaf pledged “My Government commits to continuing the effort to submit laws under much difficulty to our standing legislature to ensure the abolition [and] enforcement of the ban on Female Genital Mutilation”. Her parting gift on leaving office in 2018 was to issue an executive order abolishing FGM in Liberia.

Azango is the recipient of a number of awards, including in 2012 press freedom awards from both the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Canadian Journalists for Free Expression. In 2011, she was awarded a Pulitzer Center grant for a project on reproductive health in Africa. Then, in 2014, the deadly Ebola virus struck Africa, and Liberia was among the countries most affected. Azango, unflinching as always, turned to reporting on the harsh reality of life under the epidemic, risking her own life working on an award-winning documentary, “Living With Ebola“, broadcast by Al-Jazeera in November 2014. The film was awarded Best Documentary at the Mohamad Amin Media Awards in May 2015, given to “the best quality, most innovative content and rising platforms that are changing the face of Africa”.

Azango’s journalism is informed by her own past. In 1990, during the first Liberian civil war, her father, a judge, was dragged from their home by Charles Taylor rebels. He died in captivity. In 1996 Azango fled to Côte d’Ivoire where she lived as a refugee until her return to Liberia in 2002.

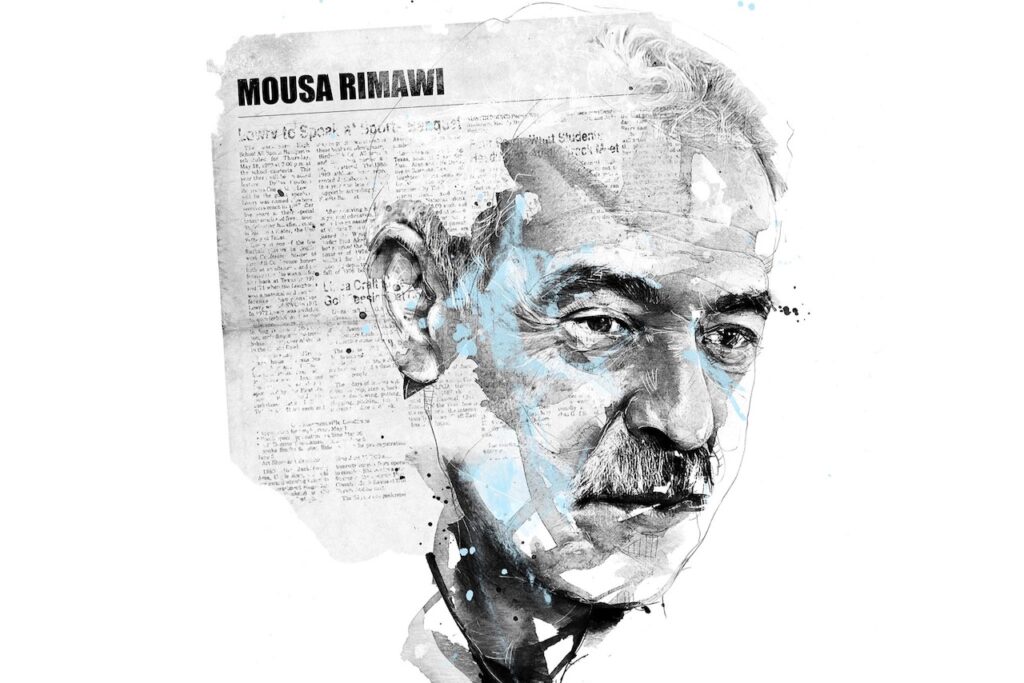

Illustration by Florian Nicolle