Italian journalist Roberto Saviano has paid a high price for exposing organised crime in Naples. But, although he now lives a drastically restricted life, this has still not silenced his pen.

"After eight years under armed guard, threats against my life barely make the news. My name is so often associated with the terms death and murder that they hardly register."

With impressive understatement, the journalist Roberto Saviano wrote in 2015: “For a lot of people, writing is just a job you do, there are no consequences. But for others, it’s not like that.” Saviano is one of the “others.” The Camorra (Naples’s version of the Mafia) has been trying to kill Saviano since 2006, the year he published Gomorrah, a book that exposed their world.

For over a decade, Saviano has been living under police protection. Every part of his life has to be planned in advance; nothing can be improvised. This has taken a severe toll:

“This life is shit – it’s hard to describe how bad it is. I exist inside four walls, and the only alternative is making public appearances. I’m either at the Nobel academy having a debate on freedom of the press, or I’m inside a windowless room at a police barracks. Light and dark. There is no shade, no in between. Sometimes I look back at the watershed that divides my life before and after Gomorrah. There is a before and after for everything, including friendship. The ones I lost, who drifted away because they found it too hard to stand by me and those I’ve found – hopefully – in the last few years. The places I knew before, and the places I’ve been since. Naples has become off-limits to me, a place I can only visit in my memories. I travel around the world, leaping from country to country as though it were a checker board, doing research for my projects, searching for any tattered remains of freedom.”

Saviano started out in journalism in 2002. His early articles appeared in magazines and newspapers such as Pulp, Diario, Sud, Il manifesto and on the website Nazione Indiana. He was also a contributor to the Camorra reporting unit of the Corriere del Mezzogiorno. But it was Gomorrah that brought him worldwide fame and misfortune.

Gomorrah is a true crime book unlike any other; it reads like a series of crime scenes viewed through the eyes of a novelist. At times cool and analytical; at other times angry and scatological. It shows us inter-clan warfare and child-gangsters in bullet-proof vests. It explores the ethical no-man’s land that exists on the edges of capitalism, where the ‘legitimate’ market intersects with the illegitimate one, where the fashion industry does questionable business deals with sweatshops in Naples using Camorra go-betweens. Above all, Gomorrah tears away the cloak of anonymity under which the Camorra has always thrived. That was not acceptable to the bosses of these crime clans.

The first sign that Saviano’s life had changed forever came in the form of a note left in his mother’s mail box shortly after Gomorrah was published; it showed an image of her son with a gun pointed at his head and the word ‘condemned’ written above it. Shortly afterwards, the police intercepted messages from jailed Camorra bosses saying that Saviano was to be killed: he was assigned two police officers for his protection. Since then, the security measures around Saviano have increased; he currently lives with a team of ten bodyguards, travelling with them everywhere in two bullet-proof cars.

The threats that Saviano has received have come in many forms. Some have been explicit; others have been indirect, but no less sinister for being so. In March 2008, during the so-called Spartacus Trial, defence lawyers for two Camorra bosses read out in court a letter (signed by the bosses) which claimed that their clients had been arrested solely because of the work of Saviano and another journalist. It was a barely veiled act of intimidation, and was recognised as such by the authorities. As a result, the bosses and their lawyers were charged with making “mafia-style” threats. Security around Saviano was strengthened. And it was needed: later that year, a former member of the Camorra revealed that there was a plan in the works to kill the journalist and his bodyguards “by Christmas.”

International concern for Saviano’s safety grew every time a new assassination plot was reported. In late 2008, six international Nobel Prize winners (including Mikhail Gorbachev, Günter Grass and Bishop Desmond Tutu) petitioned the Italian government to provide the journalist with better protection and (perhaps optimistically) defeat the Camorra once and for all; the Italian daily, La Repubblica, posted their petition online, allowing members of the public to add their names to it (which more than 150,000 did). Various Italian cities showed their support for Saviano by offering him honorary citizenship. None of this, however, made his life any easier or secure.

Ironically, one of the most recent threats to Saviano’s safety came from those responsible for protecting him. In 2018, reacting to the Italian government’s anti-immigrant, anti-Roma positions, Saviano wrote an article in which he described his fears for his country: “Italians are going backwards, socially, amid an upsurge of nationalism that displays racist animus against anything perceived to be an alien body”. In response to this and other criticisms by Saviano, the far-right, then Interior Minister, Matteo Salvini, threatened to remove the journalist’s police security.

In May 2021, the trial of Camorra member Francesco Bidognetti and his lawyer Michele Santonastaso – both on charges of threatening the lives of Saviano and another journalist – came to an end. These were the men who, during the aforementioned “Spartacus” trial, had filed a document explicitly pointing the finger at the two journalists, blaming them for the trial of the Camorra bosses. Both men were found guilty. Their trial had lasted 13 years.

Saviano went on trial for criminal defamation in November 2022, after he called Italy’s far-right prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, a “bastard”. Saviano’s comment was a response to Meloni’s call for migrants to be repatriated, and for the boats used to rescue refugees from the sea to be sunk. Saviano faces up to three years in prison if convicted.

At the first trial hearing on 15 November 2022, far-right Lega Nord leader Matteo Salvini (whom Saviano also called a “bastard”) asked to be admitted as a plaintiff in the trial. He has a separate, pending defamation suit against Saviano, initiated in 2018.

IFEX joined European and Italian press freedom groups in calling on Meloni to immediately withdraw her lawsuit against Saviano, and on Italy to bring forward anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) legislation to tackle the use of these vexatious lawsuits.

In July 2023, Saviano’s new anti-mafia TV show, Insider – faccia a faccia con il crimine (Insider – Face to face with crime), was cancelled by the state broadcaster RAI after four episodes had been recorded (the series was due to air the following November). The writer suggested that Italy’s government had pressured RAI to drop his series due to his public criticisms of government ministers. The cancellation came days after members of the ruling coalition called on RAI to cancel Saviano’s show.

In October 2023, almost one year after his trial began, Saviano was found guilty of criminally defaming Prime Minister Meloni: he was fined €1,000. PEN International attended the final hearing in solidarity with Saviano. In a joint statement, several free expression organisations (including many IFEX members) condemned the verdict:

“We believe that Roberto Saviano’s criminal conviction sets a dangerous example, which may further facilitate attempts to muzzle critical commentary on public officials and political leaders, bearing grave consequences not only for Roberto Saviano, but also for Italy’s wider press freedom.”

Roberto Saviano has received numerous prizes for his work, including, in 2011, the PEN/Pinter Prize and the Olof Palme Prize and, in 2019, the Oxfam Novib/PEN International Award for Freedom of Expression. He continues to work out of hotel rooms and secure locations, maintaining his journalistic focus on organised crime.

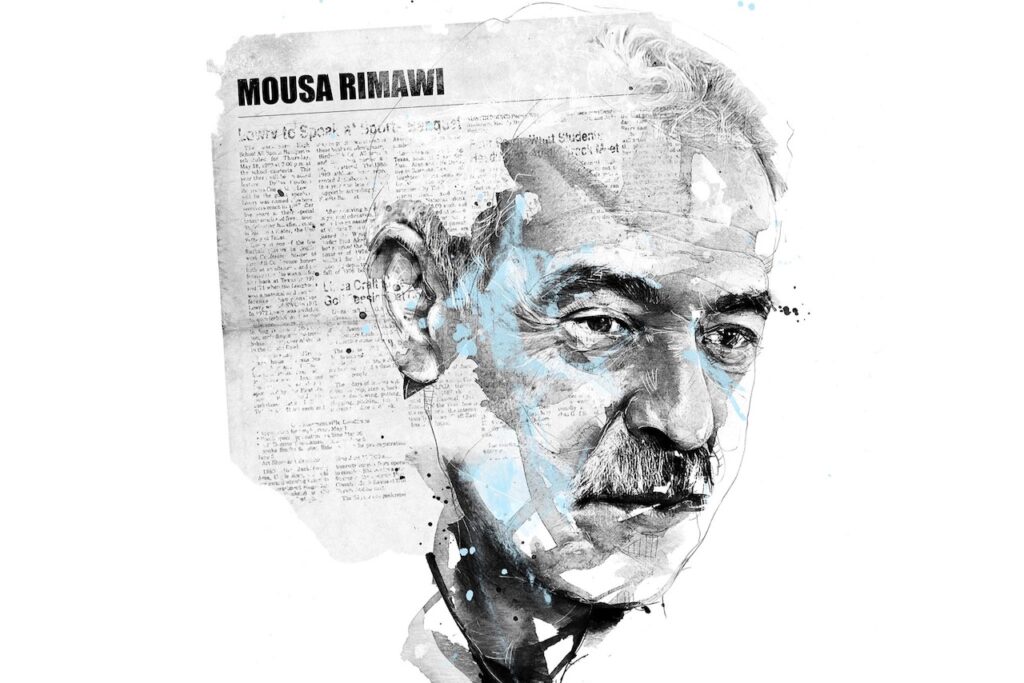

Illustration by Florian Nicolle