Despite ongoing death threats, a journalist continues her taboo-breaking campaign on behalf of DRC's hundreds of thousands of female rape victims.

Fifteen years ago some female victims of sexual violence said that they were going to die, but today, they are the leaders of their communities...they have been reborn.

The conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one that the international media largely ignores. Since 1997, when rebels ousted President Mobutu, the DRC has been a battlefield. Although the civil war that followed Mobutu’s ouster officially lasted until 2003, fighting still persists among several armed groups in the east of the country.

This apparent lack of international interest angers the Congolese journalist and women’s rights advocate, Caddy Adzuba. “Every day they talk about Iraq,” she said to El Pais in 2010, “but in the Democratic Republic of Congo 3 million people have been killed during 14 years of war…..And who knows about this? No-one!” Today, the death toll is an estimated 6 million.

Adzuba, 35, has been fighting for the war’s female victims – particularly those who have suffered sexual violence – for over fifteen years. In recognition of her work, she has received the Julio Anguita Parrado International Journalism Award and the Prince of Asturias Award of Concord. She dedicated the honorary doctorate she received from the Universitat Autõnoma de Barcelona in 2019 to women victims of sexual violence.

Adzuba’s entry into the human rights world was inspired by personal experience. When war broke out, the sixteen year old Adzuba lost contact with her family and witnessed every kind of human suffering. She was eventually reunited with her family, but what she had seen – “people killing each other for no reason” – made her realise that she, despite her young age, had a vocation: “I decided to do something for human rights.” That “something” was working for the DRC’s female rape victims.

In the year 2000, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1325, which calls on “all parties to armed conflict to take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence, particularly rape and other forms of sexual abuse, and all other forms of violence in situations of armed conflict.” The conflict in the DRC has given scant regard to Resolution 1325. In fact, as Adzuba says, it has actually “turned women into a battleground.” In the DRC, while women often have strong leadership roles within the family, victims of rape are shunned. So, sexual violence is used as a psychological weapon to first break the woman, then the family, and then the society around her. A staggering 500,000 women have been subjected to some form of sexual violence during the fighting.

In 2000, when Adzuba was just nineteen years old, she started to collect statements from women who had been raped during the conflict. She openly admits that her first attempt ended in failure because she was overwhelmed by what she had been listening to: “I couldn’t finish the interview … she talked to me for two minutes and I got up and left. I didn’t say goodbye, I didn’t say thank you to this woman. I fled.”

But Adzuba quickly adapted to her difficult work, and, as a young radio journalist, she sought out Congolese radio stations that might broadcast the first-hand testimony to sexual violence that she had recorded. However, radio bosses were unwilling to give such a taboo subject air time.

Fortunately, in 2002, the UN helped set up Radio Okapi, an independent, national radio network serving the DRC. Radio Okapi provided Adzuba with an opportunity to broadcast the statements that she had collected, and it has become the most popular station in the country. Adzuba quickly become a well-known voice on the station, and she, along with members of an organization she co-founded – the East Congo Women’s Media Association – used the airwaves to denounce sexual violence. (Adzuba has also used the radio to organise dialogue between the protagonists still fighting in the east of the country.)

Adzuba is also involved in the practical side of caring for the victims of sexual violence. She is one of the founders of the Women’s Alliance for the Promotion of Human Rights, which focuses on healing, both physical and psychological. An essential – and challenging – part of this is the use of group therapy, where the whole community is brought together and female victims talk openly about what they have suffered. The aim is to build a support network in these communities, to banish the stigma associated with being the victim of sexual violence and, thereafter, achieve social reintegration.

Speaking openly about rape in the DRC and calling for an end to impunity for the perpetrators is a risky endeavour, and Adzuba and her colleagues have received numerous death threats.

Yet, despite threats, Adzuba is an “optimist” and continues to live in the DRC. “Fifteen years ago,” she said in a 2016 interview, “some female victims of sexual violence said that they were going to die, but today, they are the leaders of their communities…(they’ve) been reborn… that makes us see that the future will be better.”

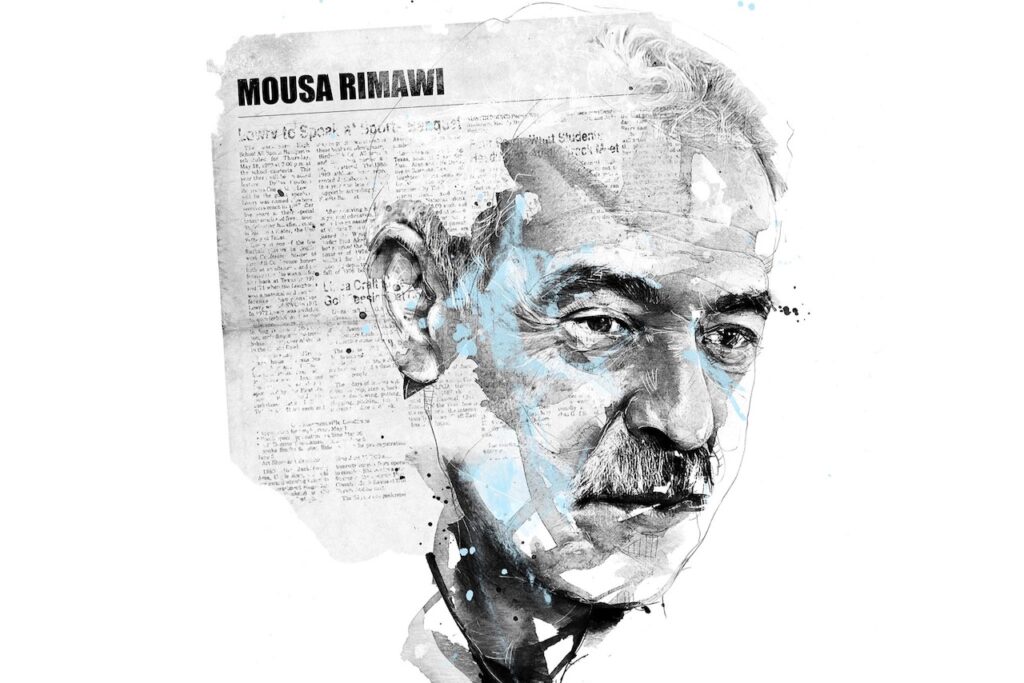

Illustration by Florian Nicolle