Jail sentences, torture and disappearances make the headlines. But, as rights defenders in Bahrain, Egypt and Turkey have found out, other forms of harassment can leave deep scars too.

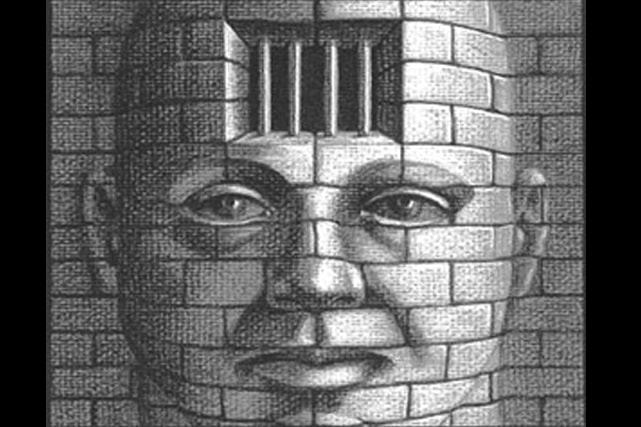

Torture. Enforced disappearances. Imprisonment. When learning about the attacks on human rights defenders around the world, these are the types of incidents that make the news. What we rarely hear about is the steady drip of government harassment many activists are subjected to on a long-term, low-level basis that affects them both psychologically and professionally but isn’t captivating enough to make headlines.

Governments around the world use various forms of repression to silence human rights defenders, and they justify their actions in myriad ways. Travel bans, judicial harassment, questioning, smear campaigns, surveillance, and intimidation are just a few of the tactics that happen to fly under the international community’s radar.

According to research carried out by Frontline Defenders, judicial harassment remains one of the most commonly used strategies around the world, the use of travel bans is on the rise, and summonses to appear for questioning before police are used to create a climate of fear within the human rights community.

In cases of judicial harassment, rights advocates are subjected to lengthy proceedings drawn out over several months and sometimes years. Even when eventually acquitted of the oftentimes-fabricated charges against them, judicial harassment diverts time, energy, and resources away from their human rights work. Every unduly postponed hearing takes the wind out of international solidarity campaigns meant to keep the individuals’ plight in the public eye.

Travel bans, often imposed without prior legal procedures, are used to stop advocates from delivering their messages to the international bodies that matter. By taking away their freedom of movement, they effectively render individuals prisoners – just of a larger prison in this case.

Questioning and interrogations, often tactics that precede judicial targeting, are used to keep human rights defenders consistently on high alert, make them aware they are being watched, and pressure them to self-censor.

All of these tactics have been used against human rights workers in the IFEX network: a global network dedicated to defending and promoting the right to freedom of expression.

As we write, at least three members of the network are being subjected to restrictions that put enormous stress on their personal and professional lives; Gamal Eid, Executive Director of the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI) in Egypt, Erol Önderoglu, journalist and free speech activist at the IPS Communication Foundation – Bianet in Turkey, and Nabeel Rajab, imprisoned head of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

All three have been targeted using the judicial system – a system meant to protect every person’s rights, yet one which has been accused of bias, partiality, and lack of independence in each of their respective countries; Egypt, Turkey and Bahrain. They are our colleagues. Their stories can be read as examples of the kind of ‘legal’ harassment that thousands of other human rights defenders are subjected to around the world.

Egypt: Frozen assets… and lives

In addition to heading ANHRI, Gamal Eid is a prominent human rights lawyer in Egypt. He has been consistently hounded by a regime determined to muzzle the last remaining independent voices in the country.

As part of a sweeping crackdown on civil society that has been taking place since 2014, Eid, alongside several other prominent human rights defenders, has been accused of illegally accepting foreign funding – a charge that, following an amendment to Egypt’s penal code in 2014, can carry a penalty of life in prison.

Eid and the other defendants are awaiting a verdict on whether their assets – and in Eid’s case, his wife’s and daughter’s bank accounts as well – will be frozen.

“The absence of the rule of law in Egypt makes me both anxious and worried at every ensuing court hearing,” said Gamal Eid. “The government and the regime are now taking revenge on us using tactics so depraved we have no experience dealing with them whatsoever.”

Since 20 April, their court hearing has been postponed three times, forcing the defendants to dwell on their looming financial woes, a punishment crippling in its own effect.

“Every time I expect the worst,” said Eid, “but I don’t really know what I should be doing, what arrangements I should make.”

The foreign funding case dates back to 2011, when 43 workers for foreign NGOs were charged with operating an organisation and receiving funds from a foreign government without a license. In June 2013, they were all sentenced from one to five years in prison, many of them in absentia.

While employees at local civil society groups implicated in the investigations were not sentenced in the 2013 case, it was not clear if they might be brought to trial at a later date. Mohamed Zaree, head of the Egypt program at the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, an IFEX member and one of the organisations implicated in the case, described to Mada Masr the looming threat posed by the proceedings as a “sword over our necks” since 2011.

In a joint statement signed by international organisations calling on Egyptian authorities to halt the crackdown, Zaree was quoted saying, “The aim of the government with the foreign funding case is not only to eliminate civil society today but to make sure that we will not be able to build up even ten years from now.”

Both Eid and Zaree, avid travelers and frequent participants at international forums and conferences, are among nearly 500 people — mostly activists, lawyers and reporters — who have been barred from travel, temporarily detained at Egypt’s airports, or deported since Abdel Fattah El-Sisi came to power in 2013.

Adding to the stress and uncertainty activists are operating under, most individuals subjected to travel bans only find out about them as they attempt to board a flight. Eid described his shock at the discovery as he prepared to board a flight to Athens, Greece on 4 February 2016.

“I felt so much anger not just because I was banned from travel but also because the decision was made without an investigation, without my knowledge. It felt like revenge was forthcoming and in a way that lacked any respect for the rule of law.”

Turkey: Erdogan’s long shadow

Erol Önderoglu is a journalist and free speech activist born in Istanbul, Turkey. Throughout his career, Önderoglu has been committed to supporting fellow journalists and defending free speech.

In an interview with Protection International, he noted: “When journalists speak about problems – the unemployment of the Alevi minority, for example – or the discrimination this community suffers, [they] should be protected by these laws, but in fact it’s not the case. These journalists are liable to jail, while nationalist circles allow themselves to set other groups of the population against minorities, such as the Kurds, the Armenians, [and] the Greeks…”

On 20 June 2016, Turkish authorities arrested Önderoglu, along with forensic doctor and head of Human Rights Foundation of Turkey Sebnem Korur Fincani and journalist and writer Ahmet Nesin. They were charged with “terrorist propaganda” for participating in a solidarity campaign in which journalists and activists have been taking turns acting as co-editors of the Kurdish daily newspaper Özgür Gündem to protest its persistent harassment by judicial authorities. He was released, pending trial, after 10 days.

Two weeks after his release, a failed military coup allowed Turkish President Recep Erdogan and his party to plunge the country into unabashed authoritarianism and a three-month state of emergency.

Önderoglu’s fears regarding his trial – scheduled to begin on 8 November 2016 – and whether he might be afforded due process, have understandably intensified as the very principles of human rights in Turkey are now in grave peril.

According to Amnesty International, as of 28 July, more than 15,000 people were detained since the coup, more than 45,000 people suspended from their jobs, 131 media outlets and publishing houses shut down and more than 40 journalists arrested, 2745 judges have been removed from their posts, 2167 were jailed, and all academics have been banned from leaving the country.

In its statement the organisation said: “We are witnessing a crackdown of exceptional proportions in Turkey at the moment.”

This is the environment in which Önderoglu awaits trial today.

Bahrain: The fear of foreign attention

In 2000, Nabeel Rajab founded the Bahrain Human Rights Society, one of the first human rights organisations in the island nation. Since then, he has helped found and run two other well-respected and independent civil society groups; the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and the Gulf Center for Human Rights. Both groups are members of the IFEX network.

In Bahrain, as in Egypt, a systemic crackdown on independent voices and civil society organisations is escalating. Rajab, who has been subjected to almost every repressive tactic in the books, sits in prison today awaiting a verdict in a politically motivated trial that has been repeatedly postponed. He was charged with insulting a public institution and the army in a tweet he posted in September 2015.

After Rajab’s former two-year stint in jail, which ended in May 2014, the prominent rights advocate spent three months lobbying European governments to support the struggle for human rights and justice in Bahrain. A few months later, and more than a year before his most recent arrest, he was banned from travel.

“It wasn’t the tweet that upset them,” he told Al-Araby Al-Jadeed in an interview. “That was the excuse. They wanted to stop my international work. They want to silence me, stop me travelling abroad.”

Travel bans have increasingly been used as a form of reprisal against human rights defenders and opposition activists in Bahrain. Most recently, the government prevented 10 rights advocates from traveling to Geneva for the Human Rights Council, where they planned to deliver interventions before the UN regarding the current state of affairs in their home country.

Rajab is being subjected to more extreme pressures. He is in deteriorating health, in solitary confinement, awaiting news of his fate.

Scars that go unnoticed

In too many parts of the world, human rights defenders – men and women dedicated to bringing justice and respect for human rights to their communities at any cost – are being targeted with persistent, low level but ultimately demoralizing and paralyzing forms of harassment by their own governments.

When we read headlines of a final verdict, “Bahraini activist sentenced to life in prison”, “Egyptian court convicts 43 NGO employees”, or “Acquittal of human rights defender and 16 others”, we are rarely aware of the months or years of harassment these individuals often endured prior to making the news. These are men and women who have stood up to steadily increased repression, aware of the possible consequences, but unwilling to give up.

When asked whether the tactics used against him are affecting his ability to do his work, Eid responded, “As long as we remain out of jail we will keep defending what we think is right and just; freedom of expression and the rule of law.”

Gamal EidHossam el-Hamalawy/ Flickr

It felt like revenge was forthcoming and in a way that lacked any respect for the rule of law.

Erol Önderoglu RSF/Erol Önderoglu

Nabeel RajabREUTERS/Hamad Mohammed/File Photo