In an interview with IFEX, cartoonist Khalid Gueddar, who recently launched the first-ever satirical weekly newspaper in Morocco, discussed his new venture, the challenges that stand in his way, and his aspirations for the future of satire in Morocco.

Contrary to common Western misperceptions, satire has long existed in the Arab world as a way to make sense of and challenge unjust situations, despotic regimes, and societal intolerance.

As the region hurtles towards Islamic conservatism and further descends into turmoil, satire has remained resilient in the face of repression. In fact, it has even thrived.

In Morocco, a country that has avoided much of the strife and bloodshed that surrounds it, there has been a rapidly declining tolerance for dissent. The right to freedom of expression – a right that has only been guaranteed in the Moroccan constitution as recently as 2011 – is being surrendered in exchange for promises of security and stability.

For decades, Moroccan journalists, cartoonists, and analysts have had to navigate a field of journalism that one reporter has likened to a minefield. “You never know when something is going to blow up,” said investigative reporter Ali Anouzla, who risks up to five years in prison under Article 41 of the current press code, which makes it a crime to publish anything that “harms the Islamic religion, the monarchic regime, or territorial integrity.”

But how is ‘harm’ determined? Is a mere mention of the monarchy grounds for persecution? What about a drawing criticizing an Islamic imam for misconduct? Or, as Anouzla did, posting an article to his news site about a jihadist video?

The language in Morocco’s press code and its constitution regarding the right to freedom of expression is extremely vague. As a result, Moroccans continuously fine-tune their sense of where the editorial ‘red lines’ lie, i.e. what, if reported on, will absolutely get them in trouble – and avoid crossing those lines.

It is in this environment that the renowned Moroccan cartoonist Khalid Gueddar – a man who has himself been hounded by the authorities, religious figures, and influential politicians – decided to launch the first-ever weekly satirical newspaper in Morocco. He called it Baboubi, and declared that it would not respect ‘red lines’ or societal taboos.

To reach as wide an audience as possible, Gueddar chose to publish the newspaper in Darija, or Moroccan Arabic – a language unfamiliar to most other native Arabic speakers, but one with which Baboubi would be accessible even to the least educated in Moroccan society.

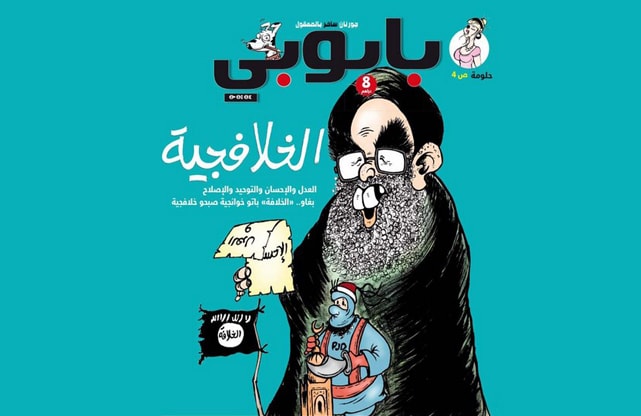

Baboubi‘s first issue, published on 12 May 2016, did not pull any punches. It mocked Islamic movements working to establish a caliphate, critiqued parliament over a decision made by one of its committees to legalize the employment of minors, and ridiculed TV programming set for the month of Ramadan. Since then, the newspaper has tackled issues of corruption in relation to the Panama Papers, the country’s convoluted relations with the United States, and extremism and radicalisation in Morocco and the West alike.

IFEX spoke with Gueddar to discuss his new venture, the challenges that stand in his way, and his aspirations for the future of satire in Morocco.

You launched Baboubi originally in 2011. What happened?

Our first attempt at launching Baboubi on the Internet was an endeavor to find out how interested Moroccans are in satire as a genre. Our experiment proved to be successful — Moroccans were indeed interested, and were keen on engaging with us and debating amongst themselves the issues we presented in satirical form. The website became one of the three most-read websites in the country. Unfortunately, it had to be halted because of financial difficulties.

You have said that Baboubi is a newspaper that does not respect taboos. Does Moroccan society today accept and respect freedom of expression without “red lines”?

The Moroccan reader cares about quality. Moroccans have been waiting for journalism that can break stereotypes and transcend the red lines that restrict freedom of expression. However, the current state of Moroccan journalism has created a disdain in the Moroccan reader for print journalism. The media lack professionalism. They skirt away from the tough subjects, avoid criticising the government, the king, or powerful individuals. There has been a major decline in the real role of Moroccan journalism, which should be to expose corruption and inform the public of news that affects them. Baboubi, on the other hand, does not believe in red lines. We respect the law, but we do not recognize these red lines as law.

What are some of the biggest red lines in Morocco today?

The biggest issues considered red lines in Morocco today – where a mere conversation on the topic can instigate strong feelings and reactions – are sex, religion, and the king. The issue of the Western Sahara was a red line in the past but it is not so taboo anymore.

Insulting religion is a very serious one. I have, in the past, been summoned to the judiciary for investigations because of cartoons deemed offensive to religion. One cartoon in particular – critiquing an imam who is alleged to have solicited a prostitute in a mosque in Fez – led to my detention in 2012.

I was interrogated for six hours under accusations that I offended Islam.

You said in a previous interview that Moroccan law is starting to protect taboos more than it protects freedoms. Can you expand on this?

The press law being enforced in Morocco today protects the state and societal taboos. Most clauses within the law are dotted with vague and broad terms that can easily be misused. At its core, this is a law that protects and panders to the perceived sanctity of certain concepts.

If we truly want freedom of expression in this country, it has to be complete freedom. Without red lines. Without taboos. But of course, we are required to work within the framework of the current law, despite it being a defective one. So we do not encroach on the law, but we do criticize it in order to reform it.

At the end of the day, if we are targeted judicially, we will be sentenced – not based on taboos or red lines – but according to legal provisions. These legal provisions are what we aim to change. These provisions are what we want Moroccans to learn about and pressure their government on, as they are ultimately what restrict our right to freely express ourselves in this country.

Do you worry about a potential backlash in response to some of your more controversial cartoons?

Certain negative reactions to our cartoons are of course possible, but I don’t think they will be in any way similar to the attacks on Charlie Hebdo. We are here to rattle some of the regressive concepts and ideas that have been entrenched in the Moroccan reader’s psyche. Such thoughts, at the end of the day, are what lead to radicalisation and eventually, violence.

Baboubi has been likened to Charlie Hebdo many times in the media. How do you feel about that comparison?

The one thing in common is that they are both satirical newspapers. Charlie Hebdo draws for the French, and Baboubi draws for Moroccans. In its design it is similar to Charlie Hebdo, but when it comes to how it tackles subjects, it does so differently. We want to show people that not all satirical journalism is Charlie Hebdo. Every magazine deals with and breaks taboos according to its own methods. Baboubi depends on professionalism. We do not comment on a serious issue in a clownish way. The point is not just to make people laugh. No. We apply our role as journalists to deliver the news or the truth, but we do it satirically.

What effect do you hope Baboubi will have on Moroccan society?

We are here to show Moroccans that it is possible to mock anything at all without harming anyone. We will not only draw what we think will please the reader, we will draw what we must draw to be able to change certain damaging concepts ingrained in our culture. We want to help enlighten Moroccan society. We are not here to offend Moroccans but to help them, in as tactful a way as possible, to accept and embrace criticism, and to encourage them to speak about and discuss issues previously considered forbidden.

What’s next for you and for Baboubi?

Baboubi, the newspaper, is just the beginning of a huge project. This project will include two electronic websites, one satirical news website and one satirical television program. The newspaper is here to cement this concept of satirical journalism in the Moroccan psyche and to promote the culture of satire in Moroccan society.

The cartoon in questionKhalid Gueddar