Recent attempts to suppress discussion on the 1965 atrocities show that the topic is still a sensitive one in Indonesia; at the same time, the voices clamouring for a renewed understanding of the country's national history are growing stronger.

An anniversary marked by censorship

Each October, foreigners and Indonesians alike gather in Bali, Indonesia for the Ubud Readers and Writers Festival (UWRF). It is an opportunity to be immersed in discussions about literature, art and ideas, all set against the backdrop of Ubud’s picturesque, terraced rice fields. Indonesia’s largest writers’ festival was created 12 years ago, in the aftermath of a terrorist attack in Bali. As festival founder and director Janet DeNeefe explains, “Led by the mantra that the pen is mightier than the sword, we created an international event that would bring issues to the table in a neutral space, where open discussion about big ideas and important stories could take place.”

This year’s festival included discussions with 165 authors from over 25 countries, readings, art exhibits, film screenings and more. What it did not include, however, was a series of planned events that were intended to shed light and foster dialogue on a dark period in Indonesian history in 1965 and 1966, when at least 500,000 people were killed. Facing pressure from the local authorities, the festival was forced to cancel panel discussions on the 50th anniversary of the atrocities, book launches, the screening of the documentary “The Look of Silence” by American director Joshua Oppenheimer, and a photography exhibit of women survivors of the killings.

The reaction to this development, without precedent in the festival’s 12-year history, was forceful – particularly among PEN Centres, whose mandates are to promote literature and defend freedom of expression around the world. “Pressure from the Indonesian government to silence discussion of the 1965 massacre signals a worrying deterioration of the right to free expression as well as a misguided effort to erase a horrific moment in Indonesia’s history,” said Karin Deutsch Karlekar, director of Free Expression Programs at PEN American. A PEN International statement noted that “Festivals are forums where difficult conversations are meant to take place, and by preventing these conversations, local authorities have undermined freedom of expression and kept old wounds buried.” “The Indonesian massacres of 1965 were exceptional in their scale and have had a lasting impact on ethnic relations within Indonesia,” said Salil Tripathi, chair of PEN International’s Writers-in-Prison Committee.

Within days more than 290 writers around the world, including several guests at the Ubud festival, joined PEN International by signing a statement condemning the interference and urging the authorities to rescind their decision.

However, the Ubud festival interference was not the only attempt in recent weeks to stymie discussion about the events of 1965-66. Events were either cancelled or attacked by civilians or law enforcers in various parts of Indonesia; a Swedish national was deported for visiting a mass grave in Sumatra; and “Lentera”, a university student magazine in Salatiga, Central Java was prevented from being sold outside the campus after reporting on the 1965 murders in the town.

“Fifty years of denials, evasions, and silences”

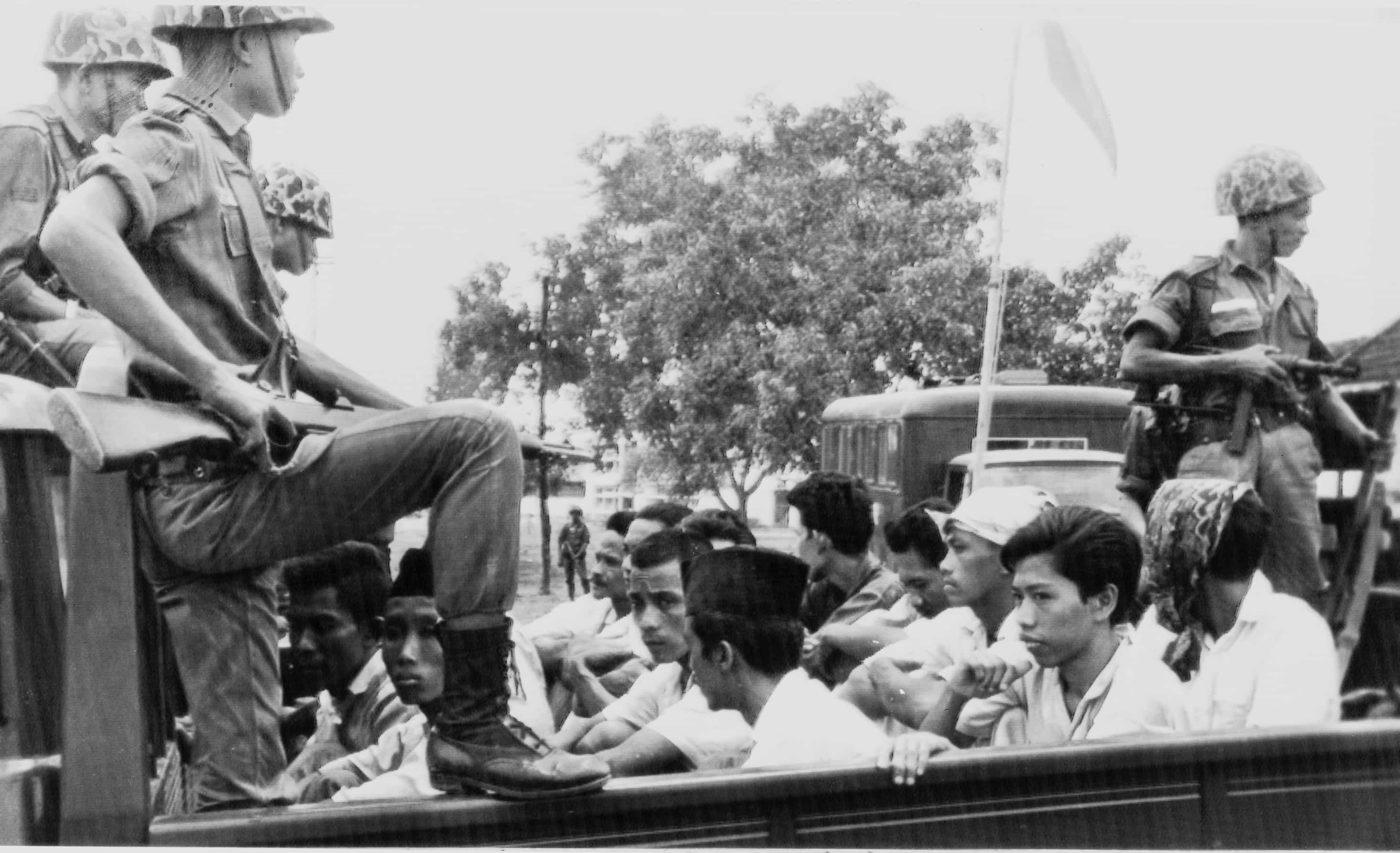

Among the genocides of the twentieth century, Indonesia’s is perhaps the least understood. On 1 October 1965, following an alleged military coup, the Indonesian government gave free rein to a mix of Indonesian soldiers and local militias to kill anyone they considered to be a “communist.” Over the next few months into 1966, at least 500,000 people were killed – the total may be as high as one million. The victims included members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), ethnic Chinese, as well as trade unionists, teachers, civil society activists, and leftist artists. They were subject to torture, rape, imprisonment, forced labour and eviction, and extrajudicial execution. The United States government provided the Indonesian Army with financial, military, and intelligence support during this period, and allegedly did so while aware that such killings were taking place.

During the 32-year rule of General Suharto, which ended in 1998, the massacre was one of many topics were off-limits. The Suharto regime either kept silent about the massacre, treating it as a non-event, or promoted the myth that the army saved the nation from communists. The six-volume “National History of Indonesia” contains one vague and factually incorrect sentence on the killings – and even that did not make it into school textbooks. Indonesian artists and novelists who addressed the issue faced repression over the years. More recently, local organisations have sought to locate the mass graves and assist the survivors, although open discussion of the events is still considered taboo.

Without transparency, there can be little hope for truth, justice, reconciliation, or redress for the families of the victims. The United States and Indonesian governments have been urged to declassify and make public all documents related to the mass killings as a key step toward obtaining justice for those crimes. In December 2014, Senator Tom Udall introduced a “Sense of the Senate Resolution” urging U.S. authorities to release the related documents from their files. Human Rights Watch supports an ongoing campaign encouraging the public to sign a petition in support of the Resolution.

While Suharto and his military officials are dead, many individuals who led the death squads or committed the crimes remain in positions of power in Indonesia. Communities still live with a silence enforced by terror.

In this 30 September 2013 photo, people watch the documentary film “The Act of Killing” in Jakarta, IndonesiaAP Photo/Tatan Syuflana

Documentary as catalyst for change

The director of the documentary whose screening was cancelled at the Ubud Festival, Joshua Oppenheimer, began investigating the killings in 2003. In the process, he learned about Ramli, a victim of the massacre whose death was not part of the official history record. After his attempts to film Ramli’s family and other survivors were met with threats, he began to film the perpetrators of the killing, who were still very much in power. They appear in his 2014 Oscar-nominated documentary “The Act of Killing”, eager to brag about the atrocities and surreally staging cinematic recreations of their crimes and fantasies.

Before “The Act of Killing” was released, Oppenheimer and his team again began working with Ramli’s family, particularly his younger brother, optometrist Adi Rukun. Adi’s brave attempts to piece together Ramli’s story and confront his brother’s killers is captured in the second documentary “The Look of Silence”.

The documentaries do not make for easy viewing – the killers’ audacity is shocking, and perfectly illustrate a climate where impunity reigns. One can only imagine the emotional toll involved in the filming process, which went on for years, and the risks taken on by those who confronted the death squad leaders and members of a right-wing paramilitary group. It isn’t surprising that the film credits include a long list of local contributors idenitifed only as “anonymous”, to protect their identities.

Oppenheimer and his crew were constantly taking stock of the danger as the situation evolved. “How do we anticipate an escape route, both literal and metaphorical, if things go badly?” he said in a July 2015 interview with the Committee to Protect Journalists. Precautions were taken during filming, including encrypting certain emails, making copies of all footage and storing it in three locations, and monitoring whether word was spreading between some of the killers and members of a right-wing paramilitary group who were interviewed in the film as to the critical angle of the films. Adi Rukun risked his life to confront his brother’s killers, and was eventually moved with his family to an undisclosed location in Indonesia; and Oppenheimer was counseled by human rights organisations that it was not safe for him to return to Indonesia.

The team was also careful about how the film was distributed inside Indonesia, to prevent it from being banned. Their distribution strategy began with invitation-only screenings, DVDs, free downloads, and uploading a version to YouTube; and because the film’s website was regularly hacked, marketing was done mostly through social media.

Despite the fears of reprisal, Oppenheimer’s films have been seen, and have sparked a discussion among the Indonesian public, the media and even the authorities, some lauding the films’ success exposing this dark reality, others raising concerns that the films give a bigger voice to the killers. In a special October 2012 edition, the Jakarta-based Tempo magazine did what it had never done since it started in 1971: interviewed civilian perpetrators from around the country, men like those featured in “The Act of Killing”. The interviews were subsequently published as a book, which the magazine decided to publish on its own as no publisher would agree to handle the sensitive material.

Ultimately, “The Act of Killing” has helped catalyse a transformation in how Indonesians look at their past, and the “Look of Silence” hints at the healing power of uncovering the truth and the possibility of reconciliation. Oppenheimer referred to the latter film as “my love letter to Indonesia”. The third chapter, as he adds, belongs to the people of Indonesia.

Marking the 50th anniversary of the genocide, an international people’s tribunal on crimes against humanity will be held in the Hague, Netherlands from 9-13 November 2015. The hope is that the tribunal’s decision will open a window of opportunity for the victims to be heard. The voices clamouring for a renewed understanding of national history are growing stronger. In the words of historian John Roosa, “Every mass grave should be marked. Stories about the massacres from the perpetrators, bystanders, and families of the victims should be recorded. More archives should be searched for documents.”