Will Colombia's journalists and public finally be able to discuss public policy without watching their backs?

This statement was originally published in Spanish on flip.org.co on 13 September 2016.

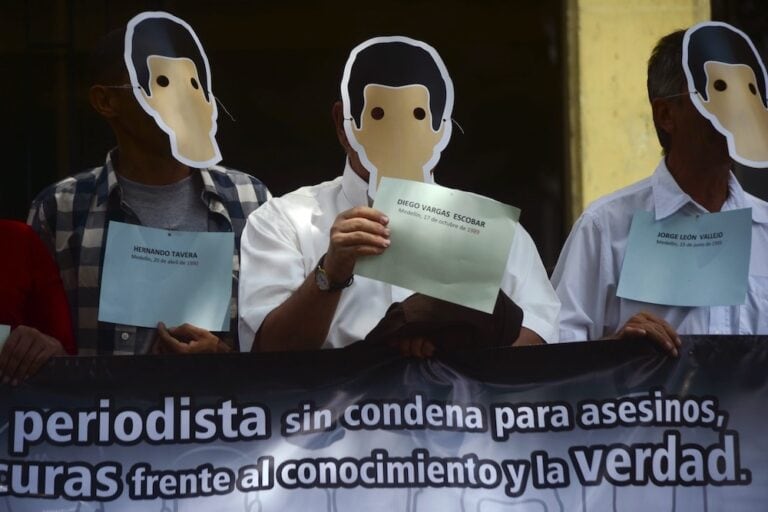

FLIP was founded 20 years ago with a mandate to protect press freedom in a country which had, for decades, maintained a shameful ranking among the most dangerous countries for practicing journalism. In the 20 years since FLIP’s inception, we have documented more than 600 aggressive actions against the press, taking into account only those incidents associated with the armed conflict. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) guerrilla group has contributed to this figure with 137 actions against the press, including 85 threats, 13 assassinations and eight kidnappings. Meanwhile, the security forces account for 230 of the actions, including 22 threats, four assassinations and 25 illegal detentions of journalists.

FLIP believes that the Accord negotiated between the government and FARC can contribute to improved press freedom conditions in Colombia. Firstly, the Accord signifies an end to the armed confrontations that have been the principal impetus for censorship, fear and informational isolation in the country.

Suffice it to note the FARC’s silencing of the “La voz de la selva” (“The voice of the jungle”) news radio station in Caquetá by assassinating its reporters one by one; or the fact that camera operator ‘Richard’ Vélez had to flee Colombia owing to the threats he received after documenting army excesses during a protest in Putumayo. We believe the Accord opens the possibility for these cycles of censorship to disappear and for there to be fewer obstacles to press freedom in Colombia.

Secondly, the Accord includes aspects that directly address freedom of expression rights. This includes very positive commitments such as the opening of trainings and discussions regarding community radio stations and access to information. In addition, the proposal for increased transparency in the allocation of government advertising could have a significant impact on media outlet autonomy and the manner in which journalistic activities are carried out in Colombia. In 2015, FLIP conducted consultancy work for the Office of the High Commissioner for Peace (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz) regarding this issue.

There are other accords to be implemented where it will be important to have frank discussions regarding what will be of best interest for public debate. This is the case with the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz), since we hope that journalists will have free access to coverage of these processes—determination of leadership roles of regional media, government funding of content to promote a culture of peace and the 31 radio frequencies that will be administered by a FARC cooperative. We understand that these points are part of global and comprehensive negotiations and we will spare no effort in leading a broad discussion with the goal of ensuring that freedom of expression standards are taken into consideration in the implementation of these accords.

Upon presenting the need for discussion regarding elements of the Accord and reaffirming our commitment to fight for open public dialogue, with no restrictions and receptive to all stances, especially as regards the views of those who may be against official positions, we believe that the violence against journalists has eclipsed open discussion on other freedom of expression and censorship issues in Colombia.

To be able to discuss public policy regarding freedom of expression is an advance in a country that for many years has only been able to talk about journalists at risk. Violence against journalists is not going to disappear entirely, but a significant source of that violence will recede.

The serious freedom of expression consequences brought about by the armed conflict have weakened democracy: censorship has negatively impacted the possibility of an informed society and the violence created an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship. Journalists in Colombia know much more than what they publish, and they do not publish what they know because they are familiar with the violent consequences that others have suffered. We trust that the peace accord will allow for improved conditions for an informed society.