Representatives from the Media Institute of Southern Africa-Swaziland, Reporters Without Borders and Freedom House speak to IFEX about press freedom in Swaziland, in light of the recent elections.

Swaziland is a country that many people know little about.

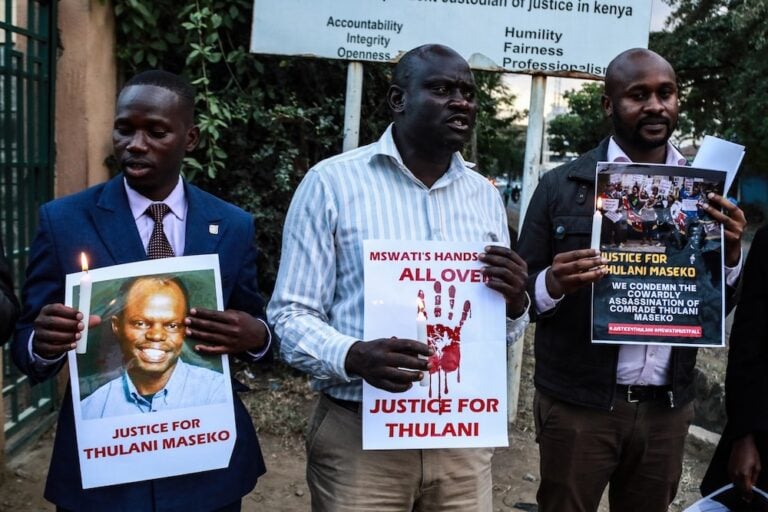

The small, landlocked nation is too-often reduced by international media to being home to the young, flamboyant King Mswati III – Africa’s last absolute monarch – and his fourteen wives.

Occasionally, too, foreign press will write about the country’s astoundingly high incidence rate of HIV, with approximately one quarter of the adult population currently infected with the virus.

But stories about the King’s lavish lifestyle and the population’s dire health situation often lack local context and critical analysis.

Perhaps, because, as Vuyisile Hlatshwayo – director of the Media Institute of Southern Africa-Swaziland notes – media in Swaziland are highly controlled by the government. The sole independent newspaper “is censored so as to ensure its own survival,” while the editor of the only independent magazine, The Nation “is on trial for offending the chief justice.”

Any form of political dissent is also repressed. Political parties have been banned since the 1970s, and peaceful protests are often dispersed by police.

So when King Mswati III changed the name of Swaziland’s political system to a “monarchical democracy” shortly before the parliamentary elections on 20 September 2013, the international community began to wonder what kind of change – if any – this would signify for Swaziland.

IFEX too, wondered if this new “marriage between the traditional monarchy and the ballot box” – as King Mswati III described it – would really effect any change on Swazi’s rights, particularly media freedom.

IFEX conducted virtual interviews with representatives from MISA-Swaziland, Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders on the subject. Here are some notable excerpts from the conversations.

The Interviewees:

Jennifer Dunham is a Senior Research Analyst for Freedom House’s annual Freedom of the Press report. Along with writing analytical reports on press freedom in several southern African countries, she has engaged with representatives of various governments on potential media reforms, spoken at conferences and to the media about the state of press freedom in Africa and around the world, and briefed U.S. government officials about trends in the global media environment.

Vuyisile Hlatshwayo has been the director of the Swazi chapter of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA) since August 2012. He co-founded The Nation and still sits as a director at the magazine. He’s also a freelance journalist and lectures part-time at the University of Swaziland (Uniswa).

Cléa Kahn-Sriber is the Head of the Africa Desk at Reporters Without Borders. She has worked on human rights and rule of law issues in Africa and the Caribbean.

On whether the name change signals real change

CKS:

According to information related by the Prime Minister of Swaziland, the king’s decision to change his country’s regime to a “monarchical democracy” came from a vision from God he had during a thunderstorm. Clearly this mystical revelation does not constitute a sound basis for an efficient regime change. There is no clear definition of any Constitutional changes and one can estimate that this is a change only in name.

Reporters without Borders thinks this declaration might be a way for the king to save face in regards to some international criticism of his authoritarian regime, especially with elections coming up and the undemocratic electoral system of the country under scrutiny.

VH:

The name change signals no change. It is window-dressing – an attempt to please locals and appease foreigners. Political parties remain banned. Many people are still fearful to speak their minds. The constitution… is still not respected, let alone enforced, by judges and parliamentarians. The king and his mother, the Queen Mother, and the government remain above the law. Citizens still have no say in who will be their head of state and prime minister. The king appoints the prime minister and cabinet members, as well as appointing ten members of the 65-seat House of Assembly and 20 of the 30-seat Senate. Citizens have no say over the Senate, as the remaining ten Senate seats are appointed by the House of Assembly. There is also a suggestion that the current king has forgotten the meaning of his role. However, to even allude to this in public inside Swaziland you could be charged under the Sedition and Subversive Activities Act 1938.

A good case to watch is that of Bheki Makhubu, editor of The Nation, a monthly magazine that arguably offers the most reliable journalism in the country. In April 2013 Makhubu was ordered by the High Court to pay a fine of E200,000 (US$ 20,000) within three days or else go to jail for two years. His crime? Writing two articles that criticised a corrupt and disrespectful judiciary. Makhubu lodged an appeal within the three days before jail-time kicked in. For the meanwhile he continues to work and publish. His appeal is expected to be heard by the Court of Appeal in November 2013, however this is yet to be confirmed.

On the state of media freedom now

VH:

Several of the election observers who recently came to Swaziland to watch the elections noted and agreed with many Swazis that Swaziland, indeed, has a “unique” system. There is no community radio here. There is one national radio station, controlled by the state. There is one TV station, controlled by the state. There is a private radio station that airs religious content. There is an on-again-off-again private TV station, Channel Swazi, that outdoes the ‘public’ broadcaster in propagating for the monarchy. There are two newspapers. One is owned by the king’s company. The other is censored so as to ensure its own survival.

JD:

The media freedom environment in Swaziland – similar to the general political climate – has been stagnant for several years, with the monarchy continuing to exert strict control over the press. This is achieved through numerous restrictive laws, such as harsh defamation laws and the Suppression of Terrorism Act, as well as a high level of official censorship, self-censorship, and state control over the media.

On what stories the media don’t cover…and why

JD:

Authorities…routinely restrict or punish coverage of government corruption, and recently attempted to restrict coverage of pro-democracy protests and public-sector strikes.

VH:

Stories that too stridently question or criticise the current political arrangement… Stories that mention how much money the monarchy is spending are particularly sensitive. Also stories that mention (not even detail) how much is being spent on cars and trips for the king’s wives and entourage. These stories, nearly always, go unreported.

In 2008 The Nation magazine did publish details of how much the king spent and how much his family takes from the country’s budget. In 2011, The Nation again published details of the king’s finances. Apart from the perception of this being un-Swazi or unpatriotic, The Nation did not face any significant backlash for publishing these stories. This has led some to question if some of the censorship and suppression comes from within. People may not say things or write things for fear of what may happen, or for the fear of losing business because they have upset the monarchy. However these thoughts can be somewhat punctured when you look at the current case involving The Nation, where the editor is on trial for criticising the judiciary and, by implication, questioning the wisdom of the king – who appoints the chief judge.

Stories that may criticise certain business interests also go unreported. In 2012 there were reports that a local construction site in Mbabane, the capital, was unsafe and workers and pedestrians were being injured unnecessarily. A local journalist told MISA that before even raising this as a story idea at the morning meeting, it was known it was a “no go area”. The reporter self-censored because they knew the owner of the construction site was friends with the owner of the newspaper.

On whether people are aware of the limitations

JD:

The fact that the government finds it necessary to employ such harsh measures – including high fines for criticizing public officials, suspending the editors of the Swazi Observer for allegedly printing negative articles about the king, and threatening to impose sanctions on those who criticize the king on Facebook or Twitter – shows that there is an active community in the country who are aware of the limits and are willing to push for change.

VH:

This is a difficult question. The better-educated Swazis, usually in the urban areas of Mbabane and Manzini, are undoubtedly aware – even if they don’t talk about censorship all that much. And despite advocacy papers by international human rights groups, which often sensationalise the already-dire situation of many Swazis, international newspapers and magazines are readily available in Swazi shops.

Swazis who are not as well educated, usually in rural areas, who are poorer and therefore have less access to outside media, may not be too aware of the lack of media freedom. While there is likely a sense that something is amiss, that certain pieces of the jigsaw may be missing, so to speak, when the current media landscape is all one has known then it’s hard to imagine something drastically different, something markedly freer. Even university students who live in urban areas struggle to afford – or simply cannot afford – a copy of the South Africa weekly newspaper Mail & Guardian. When these students do read articles in the Mail & Guardian, they instantly are aware of the extent of the censorship that exists in their country.

On getting around government controls

JD:

As in many repressive countries, the Internet and satellite dishes are two important ways that the population can access and share information; however, given the poor state of Swaziland’s economy, these are unfortunately limited to Swazis who are more affluent.

Those with satellite dishes can receive signals from independent South African and international news media, and the 21 percent of Swazis who can afford the Internet can access a broad range of news and information. An increase in access to the Internet and mobile technology are perhaps the best chances for Swazis to get around the controls placed on traditional media.

VH:

Social media is becoming more popular, particularly in urban areas where the Internet is a bit better than in rural areas – where it is almost non-existent or very poor and slow. According to internetworldstats.com, Swaziland had 95,000 Internet users in 2011. This figure has likely risen in the last few years; however the Internet connection in most places remains often slow, expensive, and unreliable.

Facebook is very popular with younger people. It is viewed with more suspicion by older people, as it seen more as a threat than an opportunity. It is often viewed simply as a tool to disrespect and cause offence and slander, and therefore it needs to be controlled and regulated or even shut down. There is a basic misunderstanding of the benefits Facebook could bring to the country – in terms of business, connectivity, sharing knowledge, and helping with organisation and planning.

In a more traditional tactic to overcome censorship, the managing editor of the Swazi Observer – a newspaper owned by the king’s company – published a ‘blank page’ opinion piece in support of embattled Nation editor Bheki Makhubu.

It is next to impossible to get past the censorship controls at the radio and TV stations. The ministry of ICT issued Public Service Announcement Guidelines stipulating that citizens must seek approval from your chief before making an announcement on radio or TV. Members of parliament are also banned from making announcements on TV and radio.

On what increased media freedom might do

VH:

This answer depends on what is happening in the wider politics and other societal forces. For instance, if media freedom is improved but other freedoms are not respected, or other institutions are still stifled, then editors and journalists may face more challenges. If media freedom is respected and more people are allowed a voice, not just reporters but also citizens and more dissenting voices, then the country will improve. The more information the better. MISA believes that good arguments need to compete against bad arguments.

In short, with more media freedom, more respect and enforcement of the constitution, and a more reliable business climate, progress would appear. An opening up of the media would help with an opening up of the mind. It would help with critical thinking; help with education, help with business. It would actually help those in power, if they could see the long-term benefits.

A voter casts his ballot at a voting station in Nhlangano, Swaziland, on 20 September 2013.AP Photo/Mongie Zulu

“Stories that mention how much money the monarchy is spending are particularly sensitive.”

King Mswati III, front, dances during a Reed Dance in Mbabane, Swaziland, September 2012.AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File

“The Internet and satellite dishes are two important ways that the population can access and share information; however… these are unfortunately limited to Swazis who are more affluent.”

Swaziland’s official photographer Musa Ndlangamandla (R) smiles as he holds a camera during the plenary session of the Africa-South America Summit on Margarita Island, September 2009.REUTERS/Jorge Silva

“An opening up of the media would help with an opening up of the mind.”