Violence and impunity are the biggest press freedom issues in Latin America, conference participants said.

(WAN-IFRA/IFEX) – Bogotá, Colombia, 14 March 2011 – More than 180 publishers and editors from 19 different countries attended the first edition of the América Latina Conference, a two-day event organised by the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA) over 9 and 10 March in Bogotá, Colombia.

During the panel entitled “Press Freedom in Latin America – One Continent, Multiple Challenges”, participants heard how censorship, physical attacks and murders, economic pressure and other measures afflict the independent press and limit its development.

“Press freedom in Latin America suffers from repressive laws, censorship, lack of access to information and lack of diversity,” said Catalina Botero, Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression for the Organization of American States. “But the single biggest problem in the region is violence against journalists and the impunity that follows,” she continued. “The authorities don’t see what they don’t want to see.”

With independent journalists imprisoned or deported and freedom of expression non-existent, a new generation of Cubans has taken to blogging and may be “an emerging ray of hope”, claimed exiled Cuban journalist José Luis García Paneque. Despite limited access to the Internet and tight censorship, this is evidence of a generational change and “a symbol that an isolated country like Cuba is moving to a 21st century environment,” he said.

“In Mexico we’re at war,” stated Rocío Gallegos, a reporter with El Diario de Juárez, a newspaper that has laid down a challenge in the battle with drug cartels, corruption and chaos. El Diario has had two reporters killed by drug cartels, while a total of 64 journalists have been killed in Mexico since 2000. Over 90 percent of these cases have not been solved and the attackers are still at large.

“Those who attack, kidnap and murder journalists act with total impunity. The problem is so big it is having an impact on both the business and editorial strategies of Mexican newspapers,” said Ms Gallegos. The newspaper drew worldwide attention to the issue with a 2010 editorial that directly addressed the traffickers, asking them “What do you want from us?”

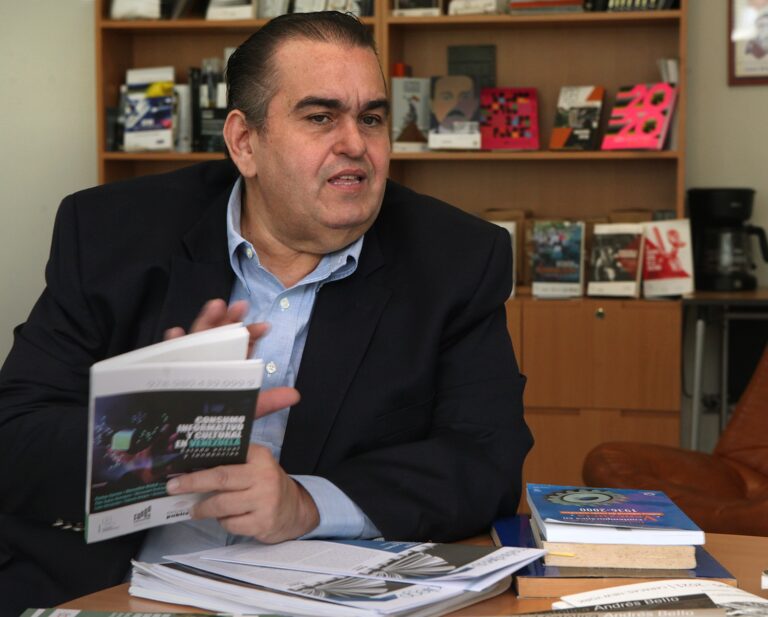

Governments may say they don’t practice censorship, but not all follow exacting standards. “Censorship is expressed as the influence of the state in the content of the media,” said Carlos Cortés Castillo, former Executive Director of the Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP) in Colombia. “I believe we can see elements in certain countries that make us think it is a strategy that some governments follow,” he continued. Mr Cortés Castillo cited examples of vague legislation in Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela and Argentina, that can potentially be used to censor the press. “Such laws have a chilling effect for press freedom,” said Mr Cortés Castillo.

“Governments everywhere spend billions of dollars on advertising, but a lack of oversight can lead to abuses,” said Eleonora Rabinovich, Director of the Freedom of Expression Programme at the Association for Civil Rights in Argentina. “Governments can reward media that support their policies by showering them with advertising, and punish others by withdrawing it.”

“It’s a very complex issue and tough to detect,” continued Ms Rabinovich, whose research shows that government advertising is a growth business. “In Mexico alone, it increased 500 percent between 2006 and 2009, while in Argentina it increased 1300 percent between 2003 and 2009.”