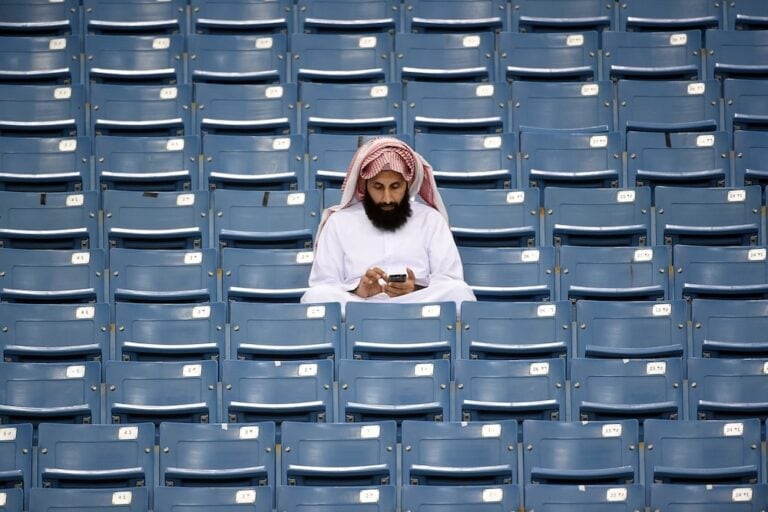

Saleh al-Mulla was charged with insulting the Emir, insulting a foreign leader, and endangering bilateral relations over critical tweets he sent before an official visit by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi of Egypt.

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 12 January 2015.

Kuwait should drop the charges against the former lawmaker, Saleh al-Mulla, over critical tweets he sent before an official visit by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi of Egypt. Kuwait authorities should also cease prosecutions against other peaceful critics.

“Saleh al-Mulla’s tweets are nothing more than political commentary,” said Nadim Houry, deputy Middle East and North Africa director. “If he is prosecuted for these tweets, it will be a textbook violation of protected free speech.”

Nawaf al-Hindal, a human rights activist, told Human Rights Watch that the authorities summoned al-Mulla for questioning on January 6, held him overnight, and then extended his detention for 10 days. On January 7, they charged him with insulting the Emir, insulting Egypt’s president, and endangering bilateral relations based on tweets that he sent during the official visit by al-Sisi that ended on January 6. He was released on bail on January 11, pending his hearing scheduled for February 15.

In one of his tweets, he criticized Kuwait’s decision to give at least US$4 billion to the al-Sisi government, writing: “Your Highness, it is unacceptable under the circumstances to give any more money to a sister nation. We have given enough, and this money belongs to the people of Kuwait.” In another tweet he wrote, “Oil is $50 a barrel … the mortification.”

Since a political crisis in June 2012, Kuwaiti authorities have ramped up efforts to curtail dissent, with courts sentencing politicians, online activists, and journalists to prison terms for exercising free speech rights. In 2014, the authorities used the constitution and a raft of restrictive laws – including the penal code; laws on printing and publishing, public gatherings, and misuse of telephone communications; and the National Unity Law of 2013 – to prosecute at least 13 people for criticizing the government or institutions in blogs or on Twitter, Facebook, or other social media.

Those accused faced charges such as harming the honor of another person; insulting the emir, other public figures, or the judiciary; insulting religion; planning or participating in illegal gatherings; and misusing telephone communications. Other charges included harming state security, inciting the government’s overthrow, and harming Kuwait’s relations with other states. At least five of those charged were convicted and sentenced to up to five years in prison and fines.

In December 2014, the parliament speaker, Marzouq al-Ghanim, announced that parliament had started legal proceedings against “those who offended the UAE leadership” in a TV show broadcast on the legislature’s official television channel. On the TV show, Mubarak al-Duwailah, a former parliament member, criticized the United Arab Emirates and its leaders over its policy, which designated the Muslim Brotherhood and its affiliate groups as terrorist organizations.

On January 5, 2015, the Supreme Court upheld a two-year sentence imposed in 2013 by a lower court on an online activist, Sagar al-Hashash, for insulting the Emir on Twitter and in a blog article addressed “To His Highness the Emir Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad.” Al-Hashash had been acquitted on September 30, 2013, but the Supreme Court reinstated the conviction and ruled that he had to complete his remaining 20 months in prison.

As a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Arab Charter on Human Rights, Kuwait is obligated to protect rights to freedom of opinion and expression, and article 36 of Kuwait’s own constitution also guarantees these rights. Yet, Kuwait maintains and enforces laws that criminalize all expression deemed “insulting to the Emir” and so fundamentally violates these rights. The ICCPR permits countries to restrict individual rights to free speech only when prescribed by law and strictly necessary to protect national security, public order, public health or morals, or the rights or reputations of others.

The UN Human Rights Committee, the body that provides the authoritative interpretation of the ICCPR, has stated categorically that “imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty” in defamation cases, because it will always be disproportionate, and has declared that defamation and insult laws should not be used to shield government leaders from criticism.

“Peaceful criticism of government policies or decisions is not only speech that should never be prosecuted, it is essential to the marketplace of ideas around politics and governance,” Houry said. “Kuwait would do well to discard its criminal defamation laws before they do even more harm to its international reputation.”