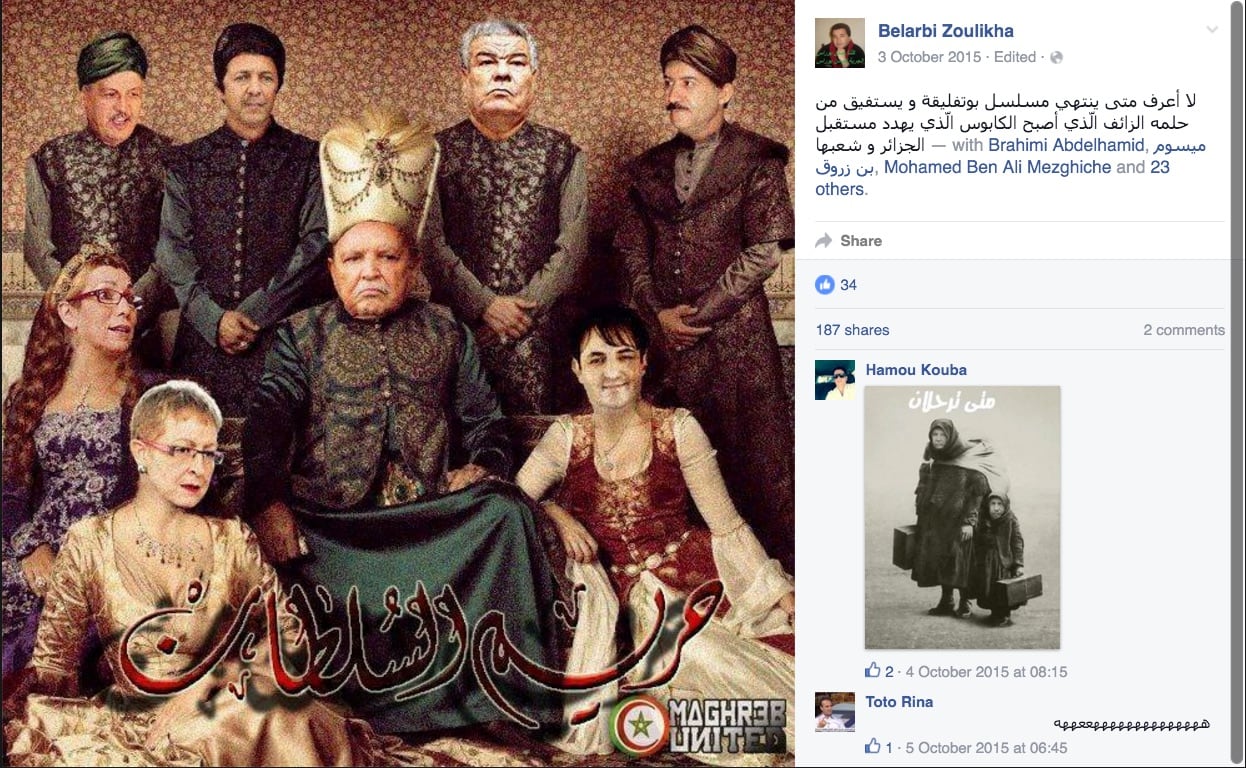

The police arrested Zouleikha Belarbi and questioned her about a Facebook post showing the faces of Algerian political figures, including President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, photoshopped as the Sultan and his entourage in a well-known Turkish television series called “Sultan’s Harem.”

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 12 April 2016.

An Algerian court has fined a human rights activist for a photo and comment she posted on her Facebook page.

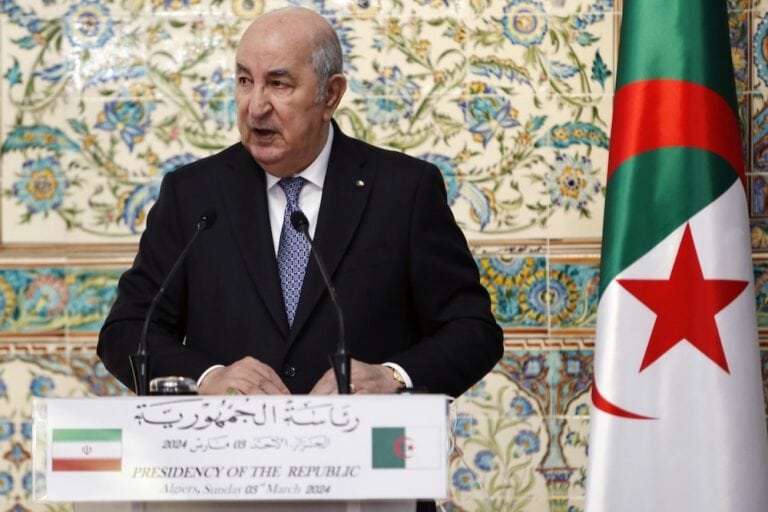

On March 20, 2016, the First Instance Court of Tlemcen convicted Zouleikha Belarbi, a member of Tlemcen’s section of the Algerian Human Rights League, of defaming the Algerian president under article 144bis of the penal code. The court imposed a 100,000-dinar (US$924) fine. Imposing sanctions for peacefully criticizing or “insulting” state officials violates international standards on freedom of expression.

“If the right to freedom of expression in the newly revised constitution has any meaning, Algeria should abolish laws that penalize peaceful criticism and satire of state officials,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch.

The police in Tlemcen, 500 kilometers west of Algiers, arrested Belarbi on October 20, 2015 and held her overnight. They questioned her about a Facebook post showing the faces of Algerian political figures, including President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, photoshopped as the Sultan and his entourage in a well-known Turkish television series called “Sultan’s Harem.” Next to the photo, Belarbi commented: “I don’t know when this series of Bouteflika’s will come to an end and when he will awake from his dream that has turned into a nightmare, which threatens the future of Algeria and its people.”

Belarbi admitted to posting the photo-montage and comment, but said that she had found the image elsewhere and had not created it.

Algeria’s constitution, as revised on March 7, 2016, guarantees the right to freedom of expression in article 48. It states that media freedom is not subject to prior censorship and that offenses cannot be punished by prison. However, it says that the right to freedom of expression may not be used “to harm the dignity, freedom, or rights of others. The dissemination of information, ideas, images, and opinions in complete freedom is guaranteed within the framework of the law and of respect for the religious, moral, and cultural values and permanent attributes of the nation” (articles 50-51).

These broadly worded provisions are incompatible with Algeria’s obligations to guarantee freedom of expression as guaranteed by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Algeria ratified in 1989.

Belarbi’s lawyer, Salah Dabbouz, told Human Rights Watch that the court convicted Belarbi of “defaming the president of the Republic,” but acquitted her on charges of defamation and “harming a state institution.”

Numerous provisions of the penal code provide prison terms for peaceful expression. For example, the punishment for distributing, selling, exposing to the public, or possessing to sell, distribute, or exhibit for propaganda purposes tracts, bulletins, or flyers that “may harm the national interest” is up to three years in prison, and for defaming or insulting the president of the republic, the parliament, the army, or state institutions is up to one year in prison.

The police confiscated Belarbi’s phone and laptop when arresting her and have not returned the laptop, Dabbouz said. Belarbi has filed an appeal, but the date has not been set.

Article 19 of the ICCPR protects the right to freedom of expression, including “freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”

In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Committee, which interprets the covenant, issued guidance to state parties on their free speech obligations under article 19 that emphasized the high value the treaty places upon uninhibited expression “in circumstances of public debate concerning public figures in the political domain and public institutions.” It said that “state parties should not prohibit criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration.” Defamation should in principle be treated as a civil, not a criminal, issue and never punished with a prison term, the Human Rights Committee has said.