(IPYS/IFEX) – The following is an excerpt from a 5 May 2006 IPYS press release: The State of Freedom of Expression and Information: 2005 Report In 2005, IPYS documented 121 freedom of expression violations, affecting 164 victims. Although the number of incidents diminished by 14.18% compared to 2004, the number of individuals effected increased by […]

(IPYS/IFEX) – The following is an excerpt from a 5 May 2006 IPYS press release:

The State of Freedom of Expression and Information: 2005 Report

In 2005, IPYS documented 121 freedom of expression violations, affecting 164 victims. Although the number of incidents diminished by 14.18% compared to 2004, the number of individuals effected increased by 7.93%. This demonstrates that the repressive actions against the press in 2005 had a greater impact and reach.

These facts are all detailed in the book “Venezuela: Freedom of Expression and of Information Situation: 2005 Report”, by IPYS and the organization Espacio Público (Public Space), released 3 May 2006 as part of World Press Freedom Day.

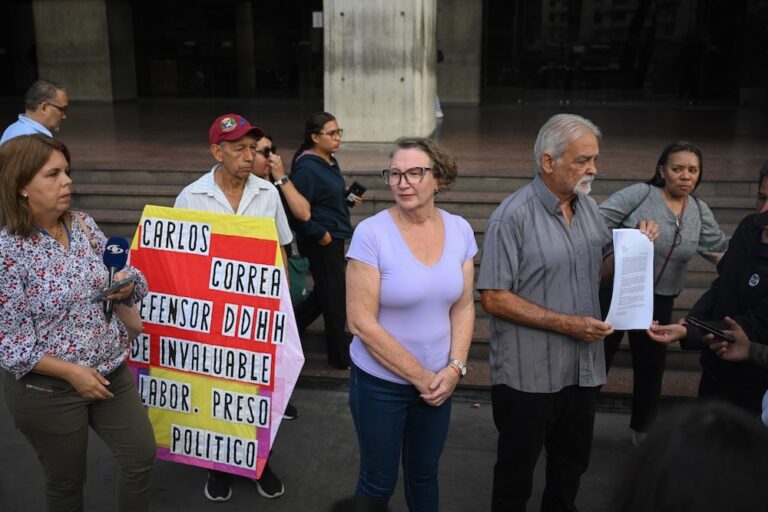

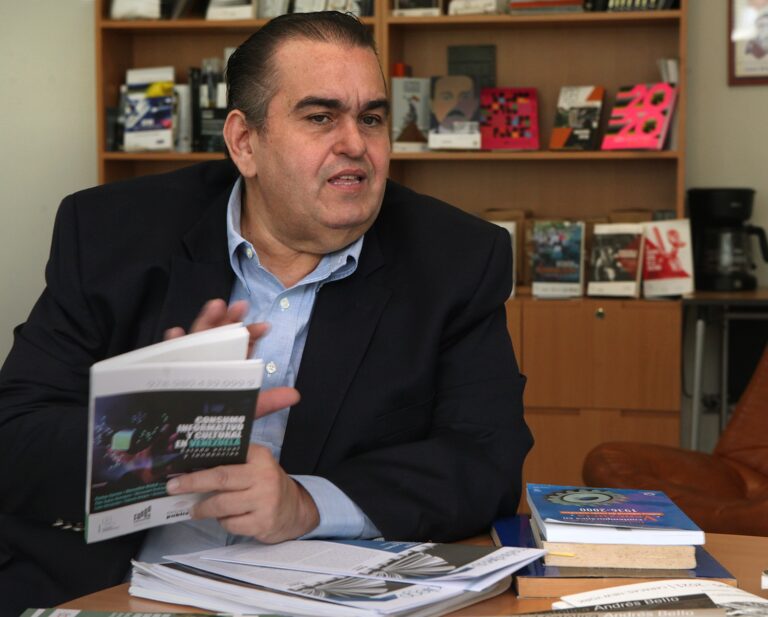

The report, coordinated by Carlos Correa, Public Space member, and Andrés Cánsales, president of IPYS Venezuela, contains five chapters that provide an exhaustive analysis of the situation of freedom of expression and information in Venezuela in 2005.

The first section of the report contains a statistical summary of violations of these freedoms.

Of the 121 incidents documented in 2005, a total of 144 violations took place, signifying a significant reduction (of 52.79%) compared to the 305 violations documented in 2004.

The most common violations were: intimidation (21.53%), legal harassment (19.44%), verbal harassment (11.11%), aggression (10.42%), threats (11.11%), censorship (9.03%), administrative restrictions (9.03%), assault (6.94%), and legal restrictions (1.39%). There were no work-related deaths documented among media workers.

With regard to the violators, in 2005 the main perpetrator was the state (69.92%) rather than individuals (30.08%), which is a change from 2004, when the distribution of responsibility was far more even: the state was then responsible for 61.78% of incidences, individuals for 38.22%.

Among individual perpetrators of violations, most fell into the category of “Other” (51.35%), which includes people that initiated legal action against journalists and demonstrators (especially student demonstrators), or who assaulted journalists and destroyed their equipment during protests related to the situation of political polarization in the country. Other significant categories are Assumed Government Supporters (24.32%), Unidentified (13.51%) and Media (10.81).

In 2005, the category Media was included because cases of self-censorship by media were documented. As well, on one occasion media outlets called for government surveillance of the electoral coverage provided by their peers.

Compared with past years, more violations took place in the interior of the country. In 2004, over half the documented cases of violations took place in the capital (67.38%). In 2005, the rate of incidence increased by 46.15% in the state of Bolivar, remained the same in Carabobo, and increased by 77.77% in the state of Aragua.

The second chapter of the book deals with the theme of censorship and self-censorship in the Venezuelan media. The text explores, using data collected by IPYS, how journalism is practiced in the country and how self-censorship is applied in the editorial rooms of the national print media.