After decades of internal armed conflict during which millions were forced from their homes, and over 220,000 killed, the implementation of peace talks between the government and rebel fighters should be cause for hope. Yet the culture of violence and impunity is deeply ingrained, with the numbers of killings and disappearances remaining horrendously high and justice for past abuses elusive.

What victims demand most – even more than reparation or justice – is the truth. The victims want to know what happened, how it happened, when it happened, where it happened and why it happened.

A supporter of the peace deal signed between the Colombian government and rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC, wave a flag during a rally in front of Congress, in Bogota, Colombia, Monday, Oct. 3, 2016. (AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

GOVERNMENT:

Republic of Colombia. President: Iván Duque, elected in June 2018 with 54% of the vote.

CAPITAL: Bogotá

POPULATION: 48.65mi

GDP: 282.5 bni

MEMBER OF:

Organisation of American States (OAS), United Nations, Unión de Naciones Suramericanas (UNASUR)

IFEX MEMBERS WORKING IN THE COUNTRY:

Foundation for Press Freedom | flip.org.co

Fundación Karisma | karisma.org.co

PRESS FREEDOM RANKING:

Reporters Sans Frontières World Press Freedom Index 2018 130 out of 180 countries

Decades of terror and hopes for peace

For more than five decades, Colombians have lived under a reign of terror as Marxist rebel groups fought against government forces, right wing paramilitaries overran large areas of the country often collaborating with the army, abuses by government forces were rampant and more recently, as narco-criminality has gripped the country. The fear of these forces left 6.8 million people internally displaced, figures second only to present day Syria. Recorded murders have topped 220,000, many of them of civilians. Thousands more have been disappeared. The killers, government forces, paramilitaries and guerrillas alike, enjoy almost total impunity, earning Colombia the reputation of being among the most dangerous places in the world.

However, from 2004 on, the numbers of killings began to decline as the political conflict waned, the demobilisation of paramilitary groups began, and later, in 2012, peace talks between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) commenced. By 2014 the numbers of deaths had levelled to around 3,000 per year, along with a steep reduction in disappearances.

Intermittent peace talks with FARC culminated in the signing of a peace agreement on 26 September 2016, a move that would lead to FARC handing over weapons to UN monitors and reintegrating into civilian life under the supervision of a tripartite monitoring group made up of the government, FARC and the UN. The peace deal was widely welcomed internationally as well as at home, with comparisons being made to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended the forty years of ‘troubles’ in Northern Ireland. The agreement was put to public vote by referendum on 3 October 2016 amidst high expectations that it would be approved. But this was not to be, and in an outcome that took its supporters by surprise, the vote to accept the treaty was lost with a majority of just 50.02%.

At the root of opposition to the peace deal is anxiety around whether former rebels could integrate into civilian life after decades of rule by violence and about the continued role of criminal networks. There was also disquiet that under the agreement, guerrilla fighters and members of the armed forces that have committed war crimes may avoid prison time and that perpetrators could be allowed to run for office. There are also other fears that new groups and criminal networks would fill the vacuum left by FARC. President Juan Manuel Santos immediately set about establishing renewed dialogue between FARC, the ‘no’ lobby and the government to “guide this peace process to a happy ending”.

On 30 November 2016, Colombia’s Congress approved a revised peace agreement that addressed several grievances from the original accord. Under the new agreement, FARC rebels would lay down their arms and, on 27 June 2017, the disarmament was complete.

Human rights defenders still in the firing line

Despite the peace deal, human rights defenders, trade unionists, indigenous and community rights activists, and journalists all remain at risk of attack. At the start of negotiations, as reported by Front Line Defenders, there was already an ‘alarming deterioration’ of safety for human rights defenders, with 69 reported killings in the first eight months of 2015 compared with 35 for the same period in 2014. By April 2017, the number of social leaders and human rights defenders reported killed in the preceding 14 months had reached an alarming 156. The continuing and escalating death toll appears to confirm fears that new right wing and criminal groups are attempting to move into areas previously controlled by FARC.

Hopes that the peace deal would bring to an end the mass displacement of large swathes of the population that in 2015 had been recorded at around 200,000 annually, although much reduced, have yet to be met. In March 2017, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees stated that 11,363 people had been displaced as irregular armed groups battled for control of areas along the Colombian Pacific coast. In the first three months of 2017 alone, 3,549 more had been forced from their homes. The majority of those affected are from the Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities, already severely affected by poverty and discrimination.

Among the courageous rights activists murdered in 2017 was Emilsen Manyoma, beaten then killed alongside her husband in January. An Afro-Colombian community leader active since 2006, she had been documenting murders and disappearances for the Truth Commission that started work in April 2017 to bring justice to the victims of the 52-year conflict. Also in January, Yoryanis Isabel Bernal Varela, an indigenous and women’s rights activist, and leader of the Wiwa tribe living on the Sierra Nevada, was shot dead. In March, Ruth Alicia Lopez Guisao, was killed in Medellin by unknown gunmen. She had been working with indigenous communities on social welfare projects in an area where paramilitaries are battling for control. The list goes on.

Women march through Bogotá, Colombia to demand an end to violence against women

Photo: UN Women

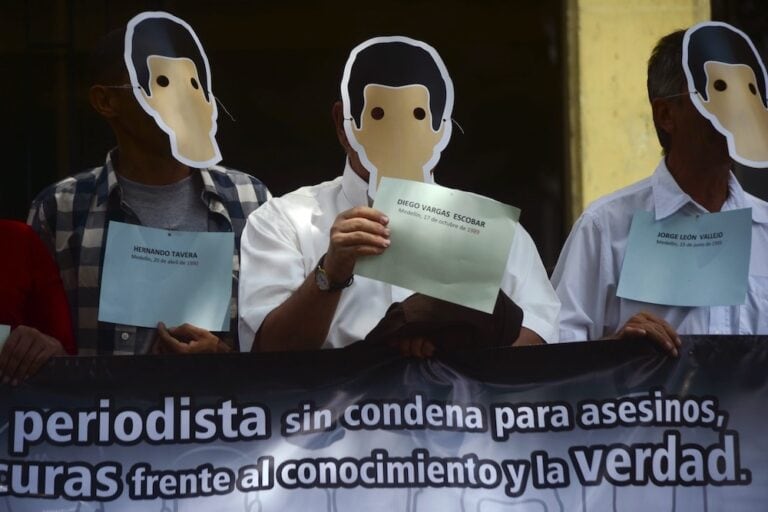

Journalists’ long wait for justice

Journalists have also been at the forefront of attacks and they, like so many other rights defenders, have found that reparation can be a long time coming.

• One example is the case of Nelson Carvajal Carvajal, a journalist murdered in 1998. After 17 years of frustration with the lack of progress of government investigations into his death, in 2015 his family welcomed the Inter-American Court on Human Rights’ (IACHR court) decision to take up the case. Carvajal’s and other journalists’ killings have been subject of an intense campaign by the Inter American Press Association (IAPA), which had sent 11 missions to Colombia over that time. In a historic verdict in June 2018, the IACHR Court found the Colombian state guilty of violating Carvajal’s right to life, guilty of failing to guarantee his right to freedom of expression, guilty of not offering judicial guarantees to investigate the murder and guilty of not protecting the journalist’s relatives.

• Reporter Jineth Bedoya, an advocate for the rights of women victims of violence, has waited many years to see justice after a process that has been described as ‘glacial’ and plagued by judicial mismanagement. In March 2016 a paramilitary fighter was convicted to 11 years in prison for her kidnap, rape and torture. Bedoya was seized outside of a Bogotá prison in May 2000 when she was reporting on alleged arms deals between paramilitary groups and state officials. She continues to press for the conviction of other perpetrators, and acknowledgement of government complicity in the attacks.

Attacks on press resume

The Colombian press monitor Fundación para libertad de prensa (FLIP) reported that in 2015 there were 147 cases of aggression against journalists, including two murders attributed to paramilitaries. These attacks continued into 2016. For example, in May that year, journalist Salud Hernández-Mora was kidnapped by ELN rebels, as were another reporter and a cameraman who set out to cover her disappearance. All were released a few days later. There was then a six-month hiatus with no attacks on the press reported between June and December 2016. Then, in January 2017, the attacks resumed, when two journalists covering an assassination were set upon and threatened against continuing their investigation. Since then organisations including the Committee to Protect Journalists have reported death threats, a knife attack, and shots fired by unknowns against journalists covering crime and human rights abuses. Two foreign journalists were also abducted by ELN rebels in June 2017 before being freed a couple of days later. The violence and threats continued throughout the second half of the year and into 2018: in August 2017, knife-wielding assailants attacked crime reporter Mauricio Cardoso in southwestern Colombia; a few months later, in November 2017, journalist Efigenia Vásquez Astudillo was fatally shot while covering riot police operations during a protest by indigenous people; in spring 2018, the famous political cartoonist, Julio César González (known as ‘Matador’) was forced off social media after being targeted with death threats and legal action by supporters of senator (and former president) Alvaro Uribe. César González had often depicted Uribe as a saboteur of Colombia’s peace process.

Another threat to journalists is surveillance and illegal spying, a situation that had become so acute that it led to the disbanding of the national intelligence agency in 2011, and the creation of a new intelligence law in 2013. The law provides harsh penalties for officers who step beyond the legal limits. However media monitors, including Fundación Karisma, point to continued spying on and wiretapping of journalists. Investigations into these breaches of privacy have been inadequate, and suffer from lack of transparency.

What hope for an end to impunity?

The decline of internal conflict in Colombia in recent years has made a significant impact on the numbers of attacks and killings. Although the peace deal is facing obstacles, the process opened debate, identified ways forward and has shown that there is a willingness to find a resolution. Yet it remains acutely dangerous to be a human rights defender, activist or investigative reporter, and new violent players are entering the game, filling a vacuum left by those who have laid down arms. This danger can only be allayed by proper investigation and prosecution of those who carry out those crimes, and by doing so, end the impunity that so many perpetrators have enjoyed in the past

MORE RESOURCES & INFORMATION

Jineth Bedoya: A Chronicle of Justice Delayed

AMERICAS 19 January 2016

Our IFEX No Impunity case profile provides a detailed history of Jineth Bedoya’s fight for justice as well as those who have assisted her along the way.