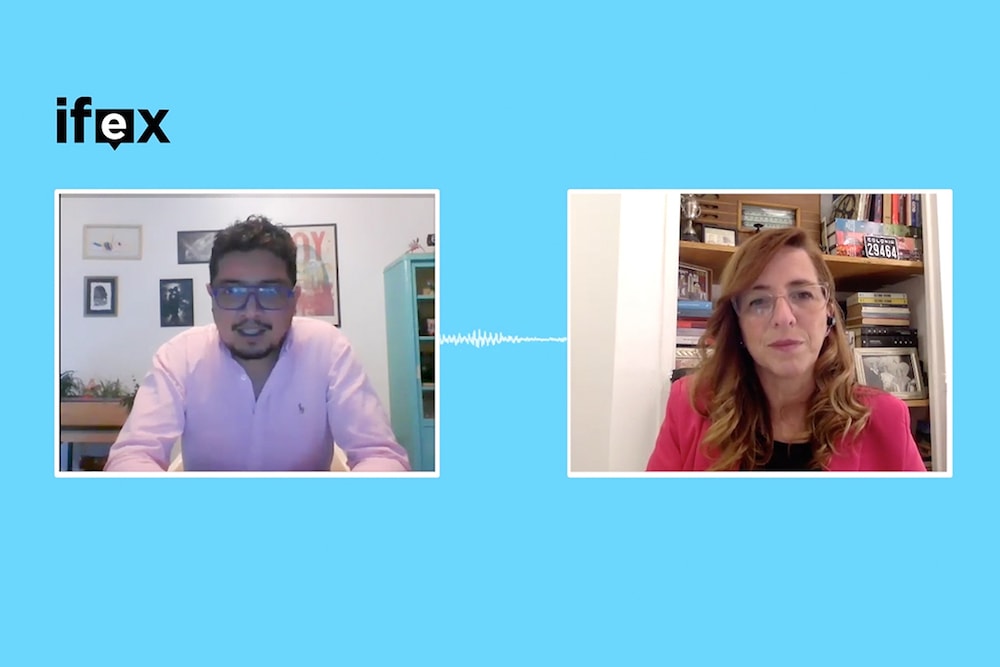

Part two of our interview with Special Rapporteur Pedro Vaca Villarreal, recorded shortly after he assumed this new role in October 2020.

IFEX asked journalist Vanina Berghella to speak with IACHR Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression Pedro Vaca Villarreal, to delve into the important challenges he faces in his newly-appointed position, review his background in the defense of freedom of expression, and discuss the priority issues on the Rapporteur Office’s agenda.

Pedro Vaca Villarreal, the new Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), has an extensive résumé and vast expertise. Vaca is renowned in Colombia for his work as a lawyer in the defense of freedom of expression, and he holds a Specialization Degree in Constitutional Law and a Master’s Degree in Law from the National University of Colombia. He was a trial attorney in lawsuits against freedom of the press violations and has provided training for judges in the fight against impunity.

During the last decade, Vaca also headed Colombia’s Foundation for Freedom of the Press (FLIP). From there he worked with other global organisations, including the International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX), as a member of its Global Council, and the NGO Freedom House, as a consultant for the freedom of the press chapter.

In the 45-minute video interview, recorded just a few weeks after Vaca was named to the role, journalist Vanina Berghella asks him about a wide range of issues and priorities for the Americas region – everything from the impact of COVID-19 on the media and the digital divide to gendered attacks on freedom of expression, journalist safety, and the responsibilities of digital platforms at a time when hate speech and misinformation are on the rise.

Watch the full interview here:

Transcription: Part Two

In Part Two of the interview (click here to see Part One), we talk with Vaca about the role of professional journalism in the face of growing disinformation and the most effective protection mechanisms available against physical threats and digital harassment.

“The protection standard we have drafted does not save lives; what can save lives is the implementation of that standard.”

Vanina Berghella: You mentioned the work of journalists with respect to access of information. I would like to focus on some aspects of the professional practice of journalism. In the context of this pandemic, we talked about the vast amount of information that is spread outside of the quality work done by journalists. What do you think the role of journalism needs to be at this moment to address the circulation of “fake news” or misinformation?

Pedro José Vaca Villarreal: After working for ten years with journalists, to me the most important thing is that journalism can survive. When I talk about journalism, I am referring to journalism large and small, and I think it faces two risks. Journalism risks becoming extinct, and this is a real risk that is not always considered in its true dimensions by everyone in society. But it also faces the risk of being seized. It is at risk of being seized by public actors, by private actors, by different sectors, even by actors from other latitudes, and that is a very sensitive matter.

I think this calls for a deep reflection. I think that a media outlet going out of business will always be bad news. Regardless of the media outlet. And I think we need to move forward, and hopefully the rapporteurship can add to that conversation, that it can contribute in such a way that every kind of media outlet is able to find a way to be stronger. Not just for the sake of that particular media outlet, but especially because of the democratic role that the media in general plays in society. A dispersed society, a society that is encapsulated in filter bubbles, a society that is dizzy from being bombarded with so much noise, such a society needs journalism. And it needs it either to identify with something or to distance itself from something. But what we cannot allow to happen is for journalism to disappear; that is what we have to work against, or prevent it from getting to a point in which it turns into something that no longer resembles itself or in which it does not fulfil the function of journalism.

VB: Speaking specifically of the work of journalists, there is an aspect that is unavoidable and that is that in some countries they are the target of extreme violence. What are in your opinion the best protection measures that can be implemented to support them in this?

PJVV: I think we have been talking about protection for years and that the protection standards exist. So, when protection is not provided, it is not because we do not know what to do; it is because there is no will to do it, because it is not done in a timely manner or because there are many obstacles that prevent that which needs to be done – protecting journalists – from materialising.

I think that what the rapporteurship needs to do now is stop reciting and start helping with implementation. And I say this emphatically because I believe that the standard alone does not save lives. The protection standard that we have drafted in the office does not save lives. What can save lives is the implementation of that standard.

I think that we are at an ideal moment, because globally there is a discussion, at the level of the United Nations safety plan for the protection of journalists against impunity, there are heightened obligations, there are commitments made by several countries to further these agendas, and what we have to do is implement existing standards.

But there is, indeed, violence, which I think is growing and is intolerable in any democratic society. And I am not talking here about the violence of organised armed groups or gangs or mafias, which is a violence that needs to be confronted by state security forces to protect journalists. There is a violence that is a bit more symbolic, which is the stigmatising discourse of public leaders. There are political leaders, public leaders, in every country in the region who are not at all ashamed to make disparaging speeches against the press. In many cases, they do not go as far as threatening journalists, but they are inviting all their followers….

VB: … to discredit them, that leads their whole community to do the same.

PJVV: It is almost like creating an atmosphere that is hostile to the freedom of expression of journalists, from a public position…

VB: It leads to self-censorship.

PJVV: … from a position of responsibility.

VB: And it generates a great deal of self-censorship by journalists, too.

PJVV: And the consequences are tremendous. The first consequence is that the followers of that political leader will be encouraged, they will feel almost like they have permission to attack journalists. But journalists will also be prompted to think that “if that is the consequence of criticising this political leader, then maybe I won’t talk about this person again.” And this is when what you were saying comes in: self-censorship.

Self-censoring is the ultimate defeat for freedom of speech, and the greatest victory for those looking to censor. Because they do not even have to do anything. They generated the conditions for the decision to be made by those who wish to express themselves freely but are not confident enough to do it.

And that is exacerbated by social media. Social media has some metrics that are to a certain extent unexplained, but which are important to people. When a journalist writes a piece and it is very well received, it makes their day, and they go to sleep feeling good about their work. But when those same metrics work against them or are used to exercise violence against women journalists; when they are used to attack, threaten, intimidate, well, that day the journalist may not sleep well, and perhaps the next day they start to think whether they really want to go on being a journalist, or if they want to go on reporting on certain issues. It is a very sensitive matter.

Safety and justice in digital spaces

VB: We were talking a little about this today with regard to the measures that could be taken, because what usually happens is that traditional legislation cannot accompany these processes. If someone wants to file a complaint because they feel completely harassed, intimidated, sometimes even threatened through social media, the legislation in force, the traditional legislation, in the various countries fails to accompany that process in a quick way or through a rapid search. There is a kind of void there, which means that in the case not only of journalists, but also of freedom of expression activists, they do not find support there.

PJVV: I am not sure there is a void. It is an issue that has to do more with timing. In my experience, in the vast majority of cases, when presented with such complaints, the institutional architecture – for example, the judicial system – will most likely fail to understand all the factors involved. The issue or challenge is not posed so much by the mechanism here, but by how prepared the judicial mechanism is to analyse a situation that is much more complex than analysing a law.

And on a second level, there is the fact that any judicial system needs due process rules that are almost unnatural if you compare them to digital dynamics. And there is also an element of anxiousness. Anxiousness to participate and anxiousness to be relevant in the public space; but also anxiousness because if something adverse happens, then we need to have something happen soon, straight away, to solve it… We need to talk about the emotional stability of social media users when the impact of any positive or negative event is exaggerated.

And this brings us back to the issue of digital literacy. It is not only about being connected, but about having the skills, or working to develop those skills, so that these things can be dealt with without resorting so easily to anxiousness, frustration, outrage, which is like a keyword in social media; it is like a match that is struck.

VB: I would also venture to add, with respect to digital literacy, that it would also be a good idea to promote it more, for example, in the judicial sphere. I think there is a gap there, too, that needs to be addressed precisely to overcome that challenge of having to work with dimensions that the law or legislation has perhaps not been prepared for until now. And in that sense, I would also like to ask you about these other methods used to target journalists, which have to do with judicial persecution or harassment of this kind. Is this element being identified as one of the methods used to silence the voices of journalists in the region?

PJVV: Yes, definitely. And it is not something new; it has been going on for quite some time. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the rapporteurship was very focused on these issues. There were cases heard by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. I think we have enough standards that can be applied in the context of this judicial persecution, which in some cases goes against freedom of expression.

But I think that part of the symptoms of a censorship disease that we need to start assessing and monitoring from the office is that there are many standards that are there, but are deliberately ignored. Or they may even be invoked under these processes, but they are disregarded without there being a better opposing argument.

I think freedom of expression and the standards themselves must also be subjected to public debate, but it seems that we are at a moment in time in which we are very disturbed by others expressing themselves. Or there are sectors that are very disturbed that someone else will dare to say something they would never say.

Perhaps what the internet is giving us, for the first time in human history, is freedom of expression as a more universal right than ever before. It seems to a certain extent paradoxical to me that international human rights treaties have been around for so long and yet when freedom of expression starts to become so universal, it feels deafening for those who could already express themselves freely. It is a right that we have to co-enjoy and it is a right we have to coexist with.

We have to coexist with the freedom of expression of others, and I think judicial harassment is a response to the inability to engage in a public debate. I think that the judicialisation of public debate – while the mechanisms are there for it – entails passing up the opportunity to engage in a public debate.

VB: You just mentioned the concept of freedom of expression, and that prompts me to ask you one of the last questions I have for you, which has to do with the fact that it is a concept that in recent years – and again with respect to the digital space – has clearly been seized by hate groups that use it to their advantage. They raise it like a banner to say whatever they want, because “there’s freedom of expression and I have a right too.”

Do you think that there are limits we need to propose when this right is exercised by a violent individual or group? In this sense, how is this contrasted with possible regulations or with the supreme right to freedom of expression?

PJVV: Saying that it is legitimate to discriminate is as absurd as saying that it is legitimate to censor. In the same way that the Office of the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression cannot accept censorship, because it would go against its mandate, it cannot accept the deliberate violation of any other right. It cannot accept that the banner of freedom of expression be used to enable or legalise a form of discrimination.

The office I now head is an integral part of a body, which is the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, that must ensure and promote a basic set of human rights where equality exists as a right. And where there is no room for discrimination. These rights need to be harmonised. We cannot put one right above another, to justify the violation of that other right. So I think there are certainly interesting debates there, very intense debates.

With this I do not mean to say that everything is crystal clear. What I mean with that is that this is a reaffirmation that this rapporteurship will not be used to justify any discriminatory actions. This rapporteurship aims to further the recovery of rights, because freedom of expression is a right that is instrumental to ensuring other rights.

Today, and you mentioned this at the beginning, we are seeing protests in several countries in the region, some of which are connected with anti-discrimination causes. Guaranteeing freedom of expression in such scenarios is also very important, and freedom of expression is in itself an engine for combating discrimination.

VB: This November 2 we celebrate the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists. What can we do to break this pattern of unresolved crimes?

PJVV: I think today there are many more tools and many more actors than there were thirty years ago. And I can say this with authority because in the foundation I worked for we monitored cases over the last three decades, and we were able to see how impunity is the rule and justice the exception. I think that is important. In these matters, the office of the rapporteur works in close association with UNESCO, which is the agency of the United Nations that heads the global agenda for November 2.

Much progress has been made in actions aimed at, for example, providing support for judicial systems in terms of training, so that they have more tools to deal with cases against impunity. Also, in conducting research, developing standards, and encouraging discussions on this subject that will make it possible to advance the goal of achieving justice. Listening very closely to what civil society is doing, and looking at the work that is being conducted by the press.

There is something very interesting in this, because despite what we talked about regarding judicial impunity, in this scenario it is also heartening to see that journalism is a sector that does not forget its own. Journalists are very aware of the right to memory. There are efforts conducted over many, many years by the Inter-American Press Association (Sociedad Interamericana de Prensa) and many other initiatives on the issue of impunity, aimed at keeping those stories alive and continuing to demand justice. And, in that sense, the office of the rapporteur is an actor that is called on to engage in that conversation, in its role of supporting states but also to raise awareness to the fact that impunity is still very much a phenomenon.

VB: Thank you very much, Pedro, for this interview, for meeting with IFEX, and for your answers to the many questions that have to do with the agenda that you are going to be pursuing from now on in your new position. So, again, many, many thanks for sharing your time with us.

PJVV: Thank you very much, Vanina. To me, it is truly like revisiting much of what I worked on in the IFEX network. And, of course, I will always be very much available from my position as rapporteur to continue advancing the freedom of expression agenda.

VB: Thank you very much.