As Algeria prepares for presidential elections this year, the amendments to the Penal Code are set to deepen repression.

This statement was originally published on cihrs.org on 8 April 2024.

New amendments to the Penal Code, adopted on 2 April 2024, add a litany of harsh and overbroad articles to the repressive legal arsenal in Algeria that could further criminalize peaceful speech and would give an already authoritarian government even more power to arbitrarily prosecute critics and political opponents, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) said today.

On 5 February, the National People’s Assembly (APN), Algeria’s lower chamber of parliament, adopted the proposed legislation aimed at amending the Penal Code. These amendments proposed to change or modify a broad range of criminal offenses, covering financial investments, fraud, increased protections for victims of sexual crimes, alternative penalties, and notably the ‘protection of security bodies.’ On 2 April, the members of the Council of the Nation, the upper chamber of parliament, confirmed these revisions to the Penal Code. The President of the Republic has yet to promulgate it into law.

These amendments strengthen the government’s leverage to stifle dissent by introducing new articles criminalizing legitimate speech and increasing penalties for several already existing offenses related to the defamation of state institutions, the disclosure of information that ‘threatens security’ or ‘harms the image’ of the security services or the army, which are all incompatible with human rights standards.

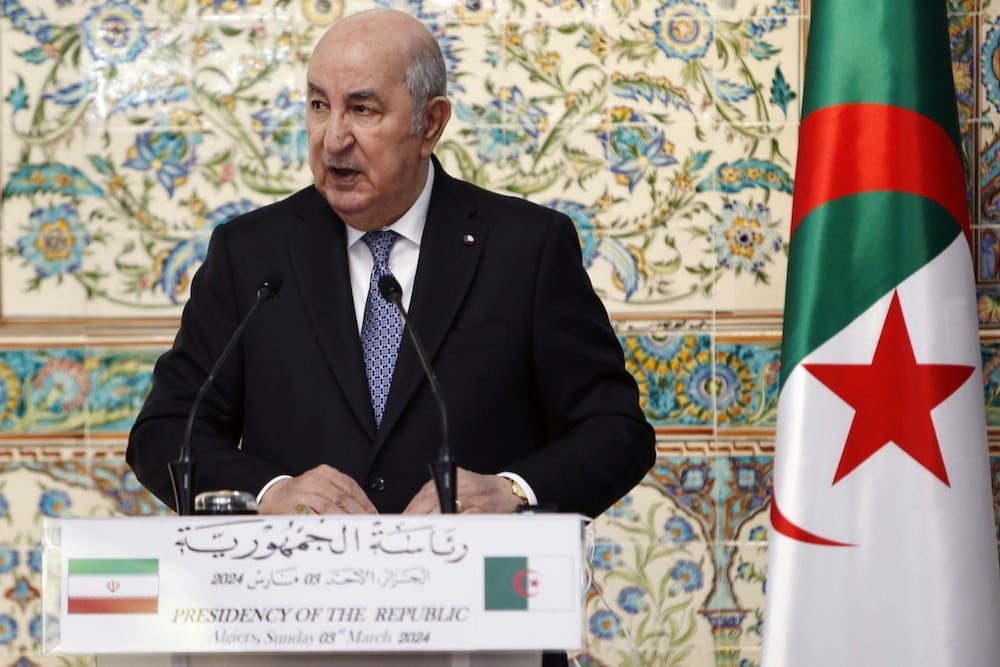

The introduction of these changes to the Penal Code come as Algeria is preparing for the 2024 presidential elections. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune’s tenure since December 2019 has been marred by a dramatic increase in the deployment of repressive laws, particularly against the Hirak. As President Tebboune seeks reelection in 2024, broadening the application of the law through these amendments could have a severe impact.

“As Algeria prepares for the presidential elections scheduled for 7 September 2024, this legislation will provide yet another weapon for the government against dissenting voices,” warned Amna Guellali, research director at CIHRS. “The authorities have a long record of punishing political dissent under the rationale of protecting national security, national interest and state institutions and symbols. These changes to the law will empower them to further erase political and social dissidence in Algeria.”

The adoption of these amendments confirms the repressive trajectory that the Algerian government has taken over the last four years. Between 2020 and 2023, several new laws were added to Algeria’s legal framework to stifle freedom of expression, association and assembly. In April 2020, Law No. 20-06 amended the Penal Code to include an article providing for up to 14 years’ imprisonment for an organization or association that receives foreign funds without authorization. The same law introduced Article 196 bis criminalizing – in vague terms – the dissemination of fake news while lacking a definition for what constitutes ‘false information.’ Presidential Ordinance No. 21-08 of 2021 changed the definition of terrorism to criminalize actions aimed at changing the system of governance by unconstitutional means. These laws have enabled the intimidation, harassment, and imprisonment of hundreds of activists, journalists, human rights defenders, and bloggers. According to activists monitoring the arrests and prosecutions of activists, there are currently 200 people languishing in Algerian prisons, detained solely for peacefully exercising their rights.

Risk of Increased Repression

Under the guise of protecting ‘national security’ and ‘national interest,’ the amendments to the Penal Code run the risk of increasing the already elevated repression of dissenting voices. The amendments introduce several broad and vaguely defined terms, particularly in articles 63 bis and 63 bis 1, which carry the penalty of life imprisonment for the act of treason through the leaking of information deemed sensitive to national security, defense, or the economy through social media platforms. While the previous version of this article established the death penalty for these crimes, it was more narrowly tied to disclosing national security information to a foreign state or its agents. The lack of a precise definition of what constitutes ‘national security secrets’ raises grave concerns about the potential for arbitrary enforcement against whistleblowers, journalists, and activists. Additionally, Article 96 escalates penalties for distributing materials deemed harmful to the ‘national interest’ and expands its scope to include audio and video materials. The lack of a clear definition of ‘national interest’ leaves this provision open to interpretations that could arbitrarily restrict legitimate political dissent and curtail the dissemination of information, further encroaching on the rights to freedom of expression and information. These articles are incompatible with the obligations to protect and respect the right to freedom of expression, which includes the public right of access to information, particularly in accordance with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to which Algeria is a party.

While governments have the right to restrict the dissemination of certain kinds of information that could seriously endanger national security, the exceptionally vague formulations in these articles and the absence of any exception or justification on the grounds of public interest could enable the authorities to prosecute those who denounce reprehensible actions by the government.

Expanded Criminalization of Free Speech

Many of the amendments increase the penalties associated with speaking out against the state, state officials, symbols, or institutions. Amendments to Article 144 increase penalties for ‘insulting’ state officials, while the Articles 148 bis 1 and 149 bis 21 introduce new crimes related to insulting symbols of ‘the national liberation movement’ and harming ‘the image of the security services and their agents.’ These changes signal an alarming trend towards penalizing criticism of the government, its officials, and abstract notions such as symbols. Such provisions are starkly at odds with international norms that uphold the right to critique public and political figures as a cornerstone of democratic engagement. Further, Article 75 broadens the scope of the criminalization of acts likely to ‘undermine the morale of the army’ by adding the security forces, which risks further stifling critical debate and scrutiny of military and security operations.

Amendment to Article 175 bis 1 extends criminalization not only to individuals who partake in illegal border crossings but also to those who might support such actions, whether directly or indirectly. This could encompass a wide range of actions, potentially involving humanitarian assistance, legal advice, or other forms of support, thereby raising concerns about the criminalization of acts of solidarity or aid to people attempting to flee Algeria, including to escape repression. As written, the amendment now specifically prescribes imprisonment of up to five years and a fine ranging from 200,000 to 500,000 Algerian dinars for anyone ‘directly or indirectly involved in facilitating or attempting to facilitate’ any acts that could be considered an illegal border crossing. The amendment appears to be a response to the Amira Bouraoui case, wherein at least four individuals were held by Algerian authorities for allegedly helping her to leave the country in February 2023.

Broadening the Definition of Terrorism

The list of terrorist acts was further expanded to include a new offense of providing ‘financial and economic resources’ to those included in the national list of ‘terrorist persons and entities.’ Given that the definition of what constitutes terrorism is very broad and was further expanded in June 2021 to include ‘attempting to gain power or change the system of governance by unconstitutional means,’ this new offense risks further criminalizing solidarity with activists unjustly included in the ‘terrorism list’ for their peaceful activism. Authorities have relentlessly resorted to these broadly worded terrorism-related charges to prosecute journalists, human rights defenders and political activists and have labeled two political organizations as ‘terrorists.’

“The new amendments add to the slew of existing laws in Algeria that need to be reformed, including on freedom of speech, assembly, association and so-called crimes against the state,” Guellali said.