The arrests of two well-known political opponents, together with the government's intention of regulating the Internet, raise serious concerns about the future of free speech in the country.

(RSF/IFEX) – Given the government’s tendency to treat any criticism or verbal attack as an act of “conspiracy against the state,” one wonders whether Venezuelans are still allowed to say anything at all about their country and their president.

The first to be arrested was former Zulia state governor Oswaldo Álvarez Paz, who said during an 8 March 2010 interview on Globovisión, a privately-owned TV station critical of the authorities, that “Venezuela has become a drug-trafficking hub.” He has been held since 22 March and is facing two to 16 years in prison on charges of inciting crime, conspiracy and spreading false information.

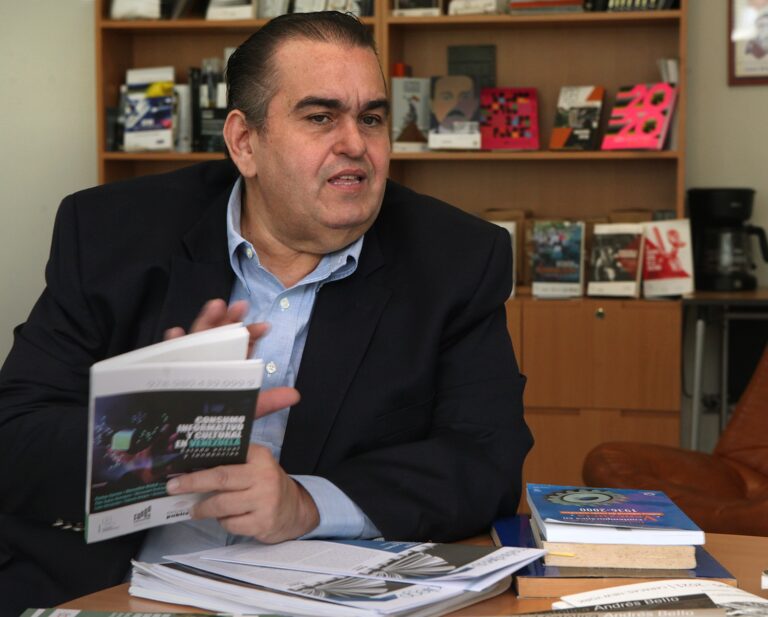

The second was Globovisión owner Guillermo Zuloaga, who criticised the government at the Inter-American Press Association’s annual meeting on the nearby island of Aruba on 21 March, condemning “the lack of free expression when a government uses its force to repress and close media, when there are more than 2,000 ‘cadenas’ and when the president uses his authority to manipulate public opinion”.

Arrested on 25 March and granted a provisional release the same day, subject to his not leaving the country, Zuloaga is facing six to 30 months in prison on a charge of insulting the president (the penalty being increased by a third when the insult is voiced in public) and another two to five years in prison for “inciting collective panic by means of false information through the press.”

The charges brought against Álvarez are doubly unfounded. How on earth could his comment be regarded as “inciting crime” or “conspiracy”? There are also absolutely no grounds for accusing Zuloaga of “inciting collective panic.” The charge of insulting the president – a monarchic heritage that has been abandoned or repealed in most democratic countries – results in an almost automatic conviction. It is also questionable whether Venezuela’s courts have jurisdiction over Zuloaga’s case as his comments were made in Aruba, a separate country. The prosecution should have been brought before an Aruban court.

Zuloaga, who has other prosecutions pending, has a fraught past. Along with other media owners, he supported an attempted coup d’état against Chávez in April 2002 but was never tried in connection with his actions at the time although arguably they could have constituted grounds for a conspiracy charge.

The government is meanwhile again using political score-settling as grounds for tightening its grip on the media at time when it is in difficulty and facing discontent. President Chávez now wants government controls to be extended to the Internet and is about to launch his own blog.

A president has a right to start a blog but does he have to justify his initiative by vowing to “bombard the network”? A president is supposed to guarantee civil peace, but Chávez’s bellicose vocabulary sounds like the “incitement” that he has accused his foes of practising.

The pledge of an Internet offensive was made in response to the posting of false information on the Noticiero Digital website’s forum section. The information, which was quickly withdrawn, was posted by visitors to the site, not by the site’s staff, whose good faith has never been in question.

There are no grounds for the heralded controls over the Internet, which reflect the government’s pointless and dangerous desire to establish its complete ascendency over the media. It is impossible to completely prevent false news and information from being disseminated. And what are the definitive criteria of truth anyway?