One year ago when the communications law was passed, IFEX members warned it could significantly restrict free expression in Ecuador. Now they are checking in on their predictions.

Today, 25 June 2014, marks one year since Ecuador’s Communications Law came into force. At the time of its passage, supporters welcomed provisions that would equally redistribute broadcast frequencies, prohibit deliberate calls for violence and restrict the hours during which adult content could be broadcast. But IFEX members said it would significantly restrict free expression in Ecuador, by imposing a regulatory framework and new obligations on all media and journalists and by giving administrative bodies control over media content.

Ecuadorian free expression organisation FUNDAMEDIOS called it a return to “the old press laws of the late 19th and early 20th century, when attempts were made to stifle and limit the work of the printed press”.

One year on, what has changed in the country’s media landscape? IFEX members have documented four reasons why there is little to celebrate on the law’s one-year anniversary:

Private media continue to monopolise airwaves

The law promised to equally redistribute broadcasting frequencies among public, private and community media – in an effort to limit media concentration and give more opportunities to community outlets. However, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) notes the inequality in broadcast frequences has remained, with approximately 78 percent going to private media, 20 percent to the public sector, and only 1 percent to community media.

New media regulatory body creates chill

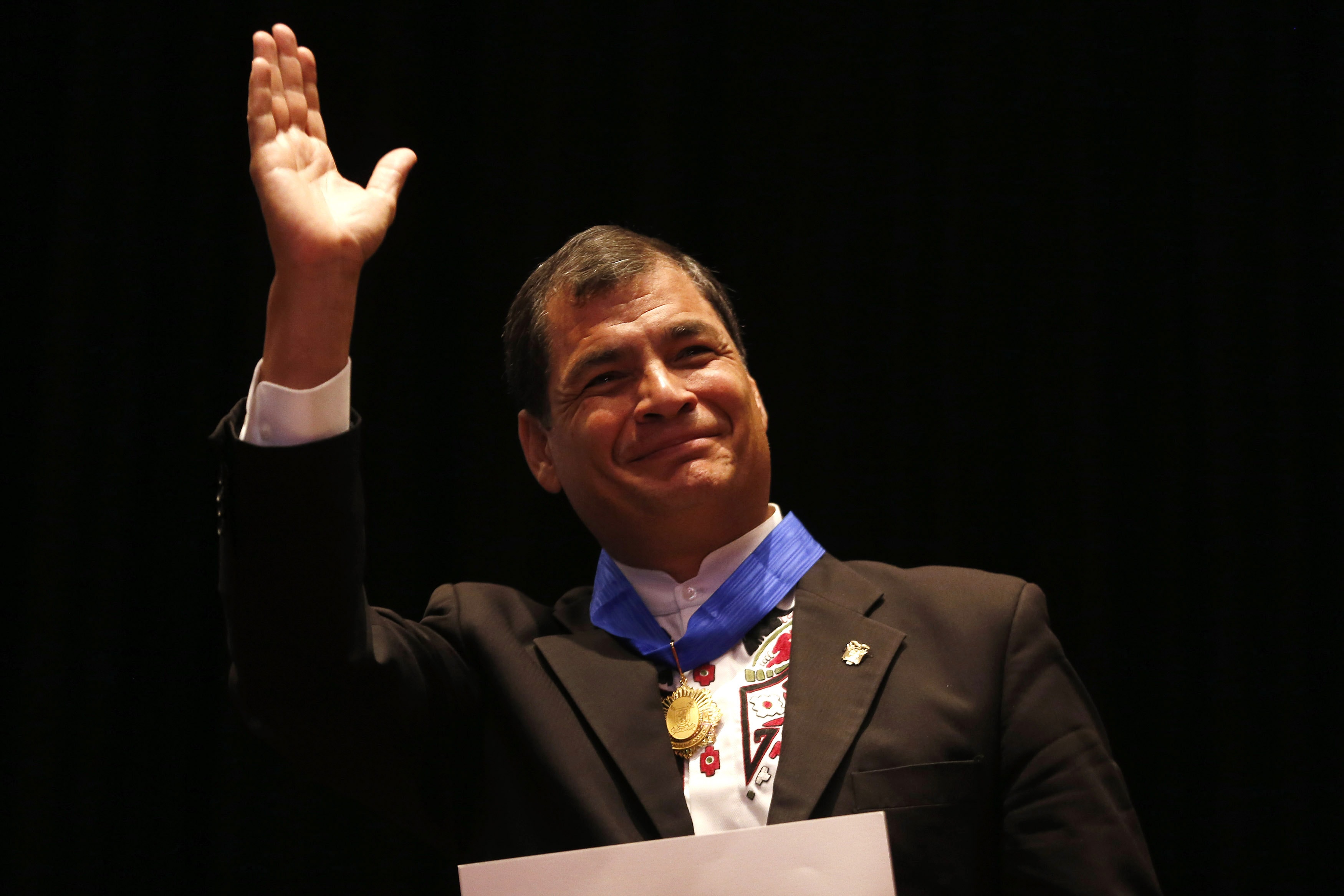

The law provided for the creation of a new regulatory body, the Superintendence of Information and Communications (Supercom), made up of three people selected from a shortlist submitted by the president, Rafael Correa. This body monitors and sanctions the media and journalists, but has no representatives from the public or the media. The International Press Institute (IPI) reported that Supercom had received 93 complaints against journalists and publications as of March 2014 and that 14 of those had resulted in fines, retractions and apologies from the press.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Supercom has been producing three media monitoring reports every day. For some outlets, this close monitoring has lead to self-censorship of contentious issues. One journalist, who declined to be named in the CPJ report, said his paper has cut back on coverage of government officials to avoid getting into trouble.

Forced media corrections, even for opinion pieces

In the past year, Supercom has forced corrections from the media 18 times. The most notable occasion was in February 2014 when Xavier Bonilla, a cartoonist for El Universo newspaper, was ordered to “correct” a political cartoon he had drawn of the violent police search and seizure of computers from a journalist’s home. Though Bonilla was forced to make a correction downplaying the violent aspects of the raid, it reads almost as a parody of the original, removing any hint of violence and replacing it with exaggerated politeness on the part of the police.

Fines for lack of public interest stories

The law also stipulates that the media must cover events that are in the public interest, saying “a deliberate and recurrent failure to report issues in the public interest constitutes an act of prior censorship”. The wording of this article is open to interpretation and misuse, as in the case of four newspapers – La Hora, El Universo, El Comercio and Hoy – which are all now facing thousands of dollars in fines for not sufficiently covering President Correa’s recent visit to Chile.

In early June Supercom received two complaints about a perceived lack of coverage of the visit, even though, according to CPJ, the trip generated very little news. According to FUNDAMEDIOS, both claims were made after the president used his 17 May public broadcast to complain about the lack of media coverage of his trip and called on his supporters to take action.

A suit, filed by 60 groups in September 2013, claiming that the law is unconstitutional was admitted to Ecuador’s Constitutional Court in January 2014. The court declined to suspend the law while the suit is being heard.

To document all free expression violations that have resulted from the Communications Law, FUNDAMEDIOS has created a blog bringing together reports from their own correspondents and international organisations. It is available here in Spanish. They call it “a space to debate the censorship effects of Ecuador’s Communications Law”.

César Ricaurte Perez, Executive Director of Fundamedios, was interviewed about the Communications Law on “On The Panamerican Highway” a radio show broadcast from Cyprus. Listen below (Show is in Spanish).

The following timeline covering the lead-up to the passing of the Communications Law and the year it has been in force is shared courtesy of RSF.

If you are having trouble viewing this timeline, click here for the http version.