July 2024 in Europe and Central Asia: A free expression round-up produced by IFEX's Regional Editor Cathal Sheerin, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

Russia continues to convict journalists who refuse to toe the Kremlin’s line on the Ukraine war; four years of repression in Belarus; access to information under threat in Slovakia; the EU’s own ‘foreign agent’ law; and the right to peaceful assembly under pressure across Europe.

The state of the right to protest in Europe

In July, a UK judge handed draconian prison sentences to five Just Stop Oil climate change activists after they were convicted of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance. The five had been planning a peaceful act of protest.

In June, police in Germany arrested a seven-year-old boy on suspicion of assaulting an officer at a pro-Palestinian demonstration after the boy allegedly hit the officer’s helmet with a flag. The child was one of six children detained at the event.

In April, police in France arrested 17 environmental defenders on “anti-terrorism” grounds after they carried out an act of protest at the site of a concrete manufacturer in Rouen.

If you’re not yet worried about the state of the right to protest in Europe, you should be.

Exercising our right to freedom of assembly, so closely related to the right to freedom of expression, is an essential way for us to be heard, to advance human rights, and push for political change.

Yet a new report by Amnesty International shows how European countries are increasingly stigmatising and criminalising peaceful protesters, deploying “ever more repressive means to stifle dissent”.

The report, Under-protected and over-restricted: The state of the right to protest in 21 countries in Europe, examines “the current state of the right of peaceful assembly” in Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK.

Based on research conducted between December 2022 and September 2023, the report provides a snapshot of how specific laws and practices were used to restrict the right to freedom of assembly during that period. Most of the examples provided by Amnesty occurred within these dates. However, some examples – where they are “illustrative of ongoing concerns” – come from outside the period in question: included among these are attempts by authorities in Europe to suppress pro-Palestinian voices since October 2023.

Some of the report’s key findings:

- Police frequently used excessive force against peaceful protesters (sometimes including children) in Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Slovenia, Serbia, Spain and Switzerland.

- There was widespread impunity for abuses by law enforcement. Countries where police frequently avoided accountability included: Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK.

- The targeted and mass use of surveillance tools against protesters is increasing. This includes the tracking and monitoring of their activities, the collection and storage of their data, and a marked increase in the use of facial recognition technology.

- The use of demonising language has been used by authorities across Europe to smear and delegitimise protests and protesters. Rhetoric referencing “terrorists”, “criminals”, “foreign agents”, “anarchists” and “extremists” is frequently used to justify introducing ever more restrictive laws.

- Environmental activists have often been described as “eco-terrorists” or “criminals” in countries such as Germany, Spain and Turkey, where the authorities have targeted them using anti-terrorism and national security laws.

- Several countries have imposed sweeping restrictions on peaceful protests (and especially on pro-Palestinian events) on spurious “national security” and “public order” grounds.

- Eight countries – Austria, Belgium, Czechia, France, Germany, Portugal, Turkey and UK – have placed a total ban on protests near government and other public buildings. In four countries – Belgium, Portugal, Serbia, Turkey – protests and assemblies are restricted to certain times.

- Racialised and marginalised groups are disproportionately impacted by anti-protest measures and policing. Restrictions imposed on protests by – or in solidarity with – “racialised groups, LGBTQI+ people, migrants, asylum seekers or refugees were justified with inferences based on racial and gender-based stereotypes, manifesting institutional racism, homophobia, transphobia and other forms of discrimination”.

Amnesty presents a long, comprehensive list of recommendations to assist states in bringing their legislation, policies and law enforcement practices into compliance with their obligations under international human rights law. Check out the report for the full details.

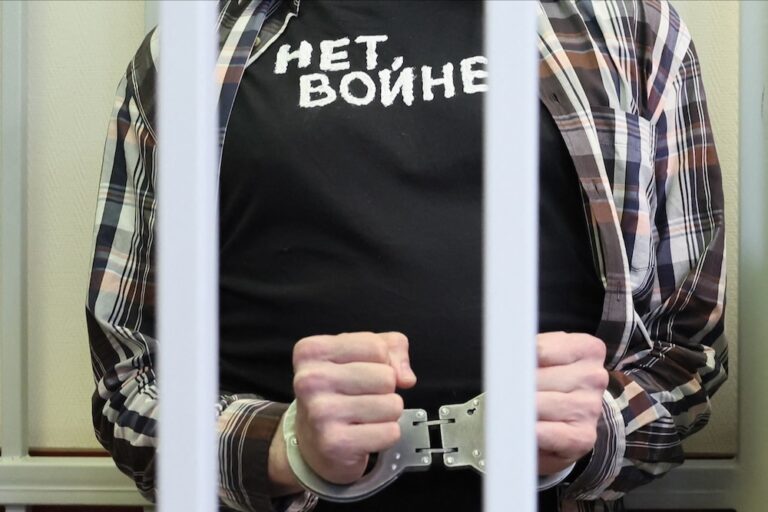

High-profile convictions in Russia

In Russia, the crackdown on independent journalism that followed Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 shows no sign of relenting. July saw The Moscow Times banned as an “undesirable organisation” and heavy sentences handed down in several high-profile cases.

US journalist Evan Gershkovich was sentenced to 16 years in prison on fabricated espionage charges. He was arrested in 2023 and accused of collecting “secret information” for the CIA on a Russian tank factory.

At a secret trial, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) reporter and US-Russian citizen Alsu Kurmasheva was sentenced to 6.5 years in prison on charges of “spreading disinformation” about the Russian army. Reporters Without Borders has launched a petition calling on the US State Department to designate Kurmasheva “wrongfully detained” and to “advocate clearly and consistently” for her.

In separate trials, journalists Masha Gessen and Mikhail Zygar were sentenced in absentia to eight and eight-and-a-half years in prison respectively. Both were convicted of “spreading disinformation” about the Russian military.

In recent weeks, Russian authorities have targeted more than a dozen exiled journalists in what the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has called an “escalating campaign of transnational repression”.

Four years of persecution in Belarus

In Belarus, August will see the fourth anniversary of the rigged presidential election that returned Lukashenka to power and launched a wave of persecution of independent media and civil society.

In those four years, independent journalism in Belarus has been decimated: most independent media outlets have now been declared “extremist” and banned. According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), there are currently 38 journalists and media workers behind bars. Another 400 have been forced into exile.

Lukashenka’s “purge” of civil society organisations (CSOs) has been equally destructive. According to Law Trend, 1,696 CSOs have been shut down since August 2020. Of these, 1, 061 were forcibly liquidated by the government; the remaining 635 opted to cease operating due to the wider repressive environment.

According to the Belarusian human rights organisation Viasna, there have been more than 5,000 politically-motivated criminal convictions since August 2020. There are nearly 1,400 political prisoners.

In July, PEN Belarus published an overview of the last four years of repression from the point of view of the cultural sector. The statistics presented are startling:

- By the end of June 2024, at least 164 workers in the culture sector were in prison or under house arrest.

- At least 1,900 members of the culture sector have been subjected to politically-motivated persecution and censorship since 2020.

- At least 960 cultural workers were arbitrarily detained.

- At least 281 culture sector workers were criminally convicted.

- At least 209 culture sector figures were listed as involved in “extremist” activities, and at least 31 were listed as “terrorists”.

In brief

Cyprus seems to be following in the footsteps of Russia and Turkey. Lawmakers are proposing changes to the law that will introduce prison sentences of up to five years for anyone caught spreading “fake” news or writing “offensive” comments. The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) has called for the amendment to be withdrawn. It is scheduled to be presented at the plenary session of the parliament in September.

The persecution of critical journalists in Turkey continues unabated, as demonstrated by the dubious sentencing in early July of eight Kurdish journalists to six years each in prison. They are charged with “membership of a terrorist organisation”. In response to this ongoing repression, IFEX joined free expression groups in calling on European governments and policy makers to do more to assist independent journalists in the country and “ensure media freedoms and fundamental rights are placed at the heart of future relations with Turkey”.

The government of Slovakia plans to restrict the right of access to information. Recent draft legislation proposes to charge fees for responding to some access to information requests and introduces the concept of “limited information”, which would allow the authorities to reject requests for information that would undermine the activity or credibility of a public authority. ARTICLE 19 called on Slovakia to withdraw the proposals.

ARTICLE 19 has also called on the EU to scrap a proposed Directive on interest representation services on behalf of third countries that “could have a serious impact on the rights to freedom of association and freedom of expression and shrink civic space”. As it stands, the current text of the Directive requires CSOs in EU countries to register if they receive funding from a foreign country and conduct “interest representation” for that country; they are also required to report on their funding and activities to the authorities, under penalty of sanctions.

In mid-July, Ursula von der Leyen was re-appointed European Commission President. IFEX members and others publicly urged her “to ensure that media freedom, the protection of journalists, and EU citizens’ access to public interest journalism remain high political priorities” during her term in office.

In Romania, Active Watch, the Center for Independent Journalism, and other media rights groups wrote an open letter to the judicial authorities, calling for the Directorate for Investigating Organised Crime and Terrorism (DIICOT) to end its ongoing harassment of journalists. The groups made their public appeal after DIICOT demanded that Rise Project journalists (who had recently published an investigation into migrant smugglers and the plight of foreign workers) share their sources with the authorities.