The internet regulation introduced in November 2020 by the Indonesian Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Kominfo) seeks to tighten the government’s grip over digital content and users’ data.

This statement was originally published on eff.org on 16 February 2021.

Indonesia is the latest government to propose a legal framework to coerce social media platforms, apps, and other online service providers to accept local jurisdiction over their content and users’ data policies and practices. And in many ways, its proposal is the most invasive of human rights.

This rush of national regulations started with Germany’s 2017 “NetzDG” law, which compels internet platforms to remove or block content without a court order and imposes draconian fines on companies that don’t proactively submit to the country’s own content-removal rules. Since NetzDG entered into force, Venezuela, Australia, Russia, India, Kenya, the Philippines, and Malaysia have followed with their own laws or been discussing laws similar to the German example.

NetzDG, and several of its copycats, require social media platforms with more than two million users to appoint a local representative to receive content takedown requests from public authorities and government access to data requests. NetzDG also requires platforms to remove or disable content that appears to be “manifestly illegal” within 24 hours of notice that the content exists on their platform. Failure to comply with these demands subjects companies to draconian fines (and even raises the specter of blocking of their services). This creates a chilling effect on free expression: platforms will naturally choose to err on the side of removing gray area content rather than risk the punishment.

Indonesia’s NetzDG variant – dubbed MR5 – is the latest example. It entered into force in November 2020, and, like some others, goes significantly further than its German inspiration. In fact, the Indonesian government is exploring new lows in harsh, intrusive, and non-transparent Internet regulation. The MR5 regulation, issued by the Indonesian Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Kominfo), seeks to tighten the government’s grip over digital content and users’ data.

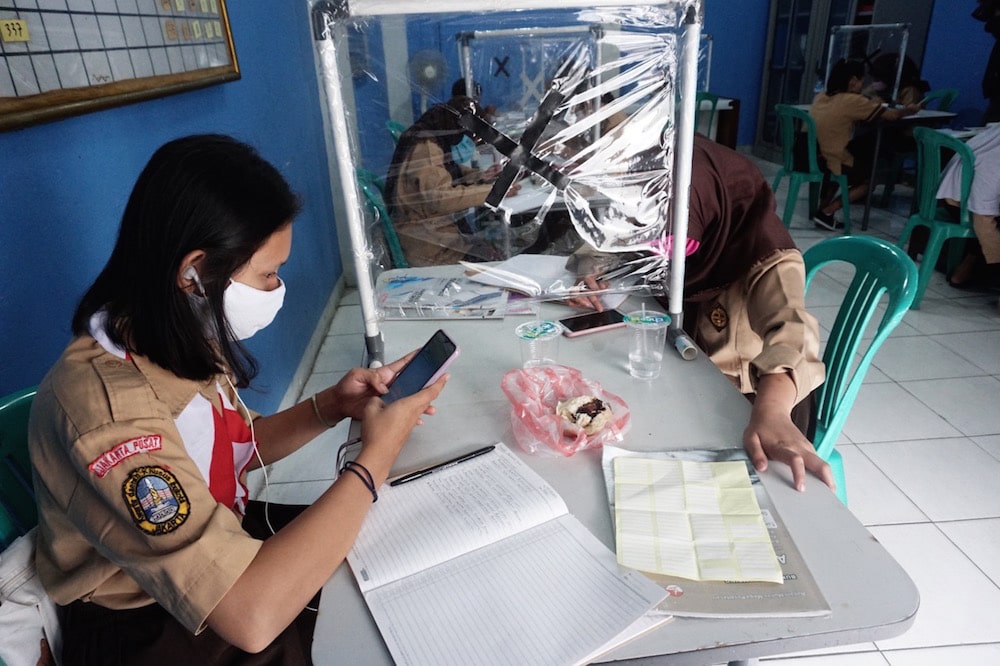

MR5 comes amid difficult times In Indonesia

The MR5 regulation also comes at a time of increased conflict, violence, and human rights abuses in Indonesia: at the end of 2020, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights raised concern about the escalating violence in Papua and West Papua and shed light on reports about “intimidation, harassment, surveillance, and criminalization of human rights defenders for the exercise of their fundamental freedoms.” According to APC, the Indonesian government has used hate speech laws, envisioned to protect minority and vulnerable groups, to silence dissent and people critical of the government.

These provisions are not only a serious threat to Indonesians’ free expression rights, they are also a major compliance challenge for Private ESOs.

MR5 further exacerbates the challenging situation of freedom of expression in Indonesia this year and in the future, according to Ika Ningtyas, Head of the Freedom of Expression Division at the Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFEnet). She told EFF:

The Ministry’s authority, in this case, Kominfo, is increasing capacity so it can judge and decide whether the content is appropriate or not. We’re very concerned that MR5 will be misused to silence groups criticizing the government. Independent branches of government have been excluded, making it unlikely that this regulation will include transparent and fair mechanisms. MR5 can be followed by other countries, especially in Southeast Asia. Regional and global solidarity is needed to reject it.

Business enterprises have a responsibility to respect human rights law. The UN Special Rapporteur on Free Expression has already reminded States that they “must not require or otherwise pressure the private sector to take steps that unnecessarily or disproportionately interfere with freedom of expression, whether through laws, policies, or extralegal means.” The Special Rapporteur also pointed out that any measures to remove online content must be based on validly enacted law, subject to external and independent oversight, and demonstrate a necessary and proportionate means of achieving one or more aims under Article 19 (3) of the ICCPR.

We join SAFEnet in urging the Indonesian government to bring its legislation into full compliance with international freedom of expression standards.

Below are some of MR5’s most harmful provisions.

Forced ID registration to operate in Indonesia

MR5 obliges every “Private Electronic System Operator” (or “Private ESO”) to register and obtain an ID certificate issued by the Ministry before people in Indonesia start accessing its services or content. A “Private ESO” includes any individual, business entity or the community that operates “electronic systems” for users within Indonesia, even if the operators are incorporated abroad. Private ESOs subject to this obligation are any digital marketplace, financial services, social media and content sharing platforms, cloud service providers, search engines, instant messaging, email, video, animation, music, film and games, or any application which collects, processes, or analyzes users’ data for electronic transactions within Indonesia.

Registration must take place by mid-May 2021. Under MR5, Kominfo will sanction non-registrants by blocking their services. Those Private ESOs who decide to register must provide information granting access to their “system” and data to ensure the effectiveness in the “monitoring and law enforcement process.” If a registered Private ESO disobeyed the MR5 requirements, for example, by failing to provide the “direct access” to their systems (Article 7 (c)), it can be punished in various ways, ranging from a first warning to temporary blocking to full blocking and a final revocation of its registration. Temporary or full blocking of a site is a general ban of a whole site, an inherently disproportionate measure, and therefore an impermissible limitation under Article 19 (3) of the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). When it comes to general blocking, the Council of Europe has recommended that public authorities should not, through general blocking measures, deny access by the public to information on the Internet, regardless of frontiers. The United Nations and three other special mandates on freedom of expression explain that “[m]andatory blocking of entire websites, IP addresses, ports, network protocols or types of uses (such as social networking) is an extreme measure – analogous to banning a newspaper or broadcaster – which can only be justified in accordance with international standards, for example where necessary to protect children against sexual abuse.”

A general ban of a Private ESO platform will also not be compatible with Article 15 (3) of the UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which states that individuals have a right to “take part in cultural life” and to “enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications.” The UN has identified “interrelated main components of the right to participate or take part in cultural life: (a) participation in, (b) access to, and (c) contribution to cultural life.” They explained that access to cultural life also includes a “right to learn about forms of expression and dissemination through any technical medium of information or communication.”

Moreover, while a State party can impose restrictions on freedom of expression, these may not put in jeopardy the right itself, which a general ban does. The UN Human Rights Committee has said that the “relation between right and restriction and between norm and exception must not be reversed.” And Article 5, paragraph 1 of the ICCPR, states that “nothing in the present Covenant may be interpreted as implying for any State … any right to engage in any activity or perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms recognized in the Covenant.”

Forced appointment of a local contact person

Tech companies have come under increasing criticism for decisions to flout and ignore local laws or treat non-U.S. countries with attitudes that lack understanding of the local context. In that sense, a local point of contact can be a positive step. But forcing the appointment of a local contact is a complex decision that can make companies vulnerable to domestic legal actions, including potential arrest and criminal charges of their local contact as has happened in the past. With a local representative, platforms will also find it much harder to resist arbitrary orders and can be vulnerable to domestic legal action, including potential arrest and criminal charges. MR5 compels everyone whose digital content is used or accessed within Indonesia to appoint a local point of contact based in Indonesia and who would be responsible to respond to content removal or personal data access orders.

Regulations requiring take down of content and documents deemed “prohibited by the Government”

Article 13 of the MR5 forces Private ESOs (except cloud providers) to take down prohibited information and/or documents. Article 9(3) defines prohibited information and content as anything that violates any provision of Indonesia’s laws and regulations, or creates “community anxiety” or “disturbance in public order.” Article 9 (4) grants the Ministry, a non-independent authority, unfettered discretion to define this vague notion of “community anxiety” and “public disorder.” It also forces these Private ESOs to take down anything that would “inform ways or provide access” to these prohibited documents.