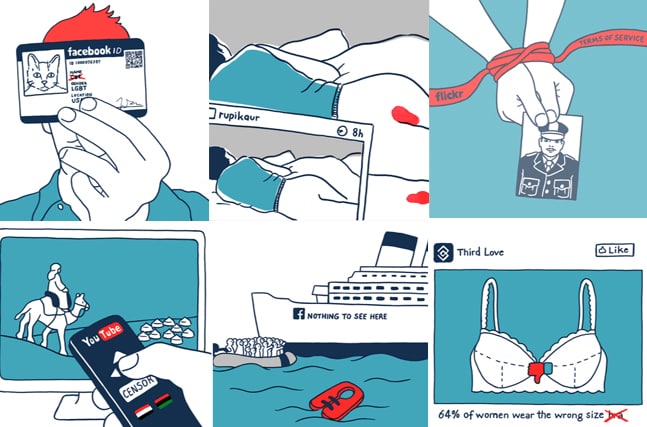

From banning female nipples to removing "shocking" violent content, social media companies have unique approaches to censorship. But which ones censor what? And what can you do about it?

The following statement was originally published on globalvoices.org on 4 November 2016.

By Afef Abrougui

From Facebook banning photos of female breasts (if they include the nipple) to YouTube’s prohibition on “shocking” violent content, social media companies play a powerful role in deciding what types of speech are most commonly seen and heard on the Internet.

These and other leading platforms have terms of use that restrict several types of content including nudity, hate speech, and violence. But these difficult-to-define rules are always subject to interpretation.

There have been numerous free-speech violations due to the overzealous implementation of these terms from the part of social media platforms. Last year, Twitter mistakenly suspended the account of activist and user Iyad el-Baghdadi, after the site’s moderators suspected that his account belonged to ISIS leader Abubaker el-Baghdadi. In another of example from the Arab region, earlier this year, Facebook removed a photo by Tunisian photographer Karim Kammoun. The photo displays bruises on the naked body of a woman victim of domestic violence.

Social media sites also remove user posts in response to government requests. Governments sometimes ask platforms to remove content with a clear and legitimate aim of protecting children from sexual exploitation, or countering violent extremist propaganda. But they also have been known exploit these policies to pressure social networking sites to remove content that would otherwise be protected by human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

The Turkish government remains by far the most exploitative of these policies, as it tops the list of governments that made content removal requests to Twitter over the first six months of 2016 with 2493 requests. In addition, during the second half of 2015, Facebook restricted access to 2078 pieces of content in response to requests made by Turkish authorities under internet law number 5651 which bans personal rights violations and the defamation of the Turkish republic’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

According to Turkish activists, their government also exploits these policies to prevent its citizens from criticizing the authorities, disseminating content related to the Kurdish cause, and even to ban coverage of political events that are of interest to the public. For instance, in March 2014, Twitter restricted access to the user account @oyyokhirsiza inside Turkey, for publishing tweets accusing a former government official of corruption, under its country-withheld content policy.

Just last month, Facebook disabled multiple accounts and pages belonging to Palestinian journalists and news sites. This came just a few weeks after the Israeli government announced an agreement with the company to remove what its describes as “inciting” content. Although Facebook later apologized for these actions, activists in Palestine and the region remain skeptical about the site’s commitment to transparency and impartiality when it comes to implementing its content-removal policies.

This assemblage of public and private interests and policies is difficult to understand from the vantage point of social media users — companies release some information about what they do and do not censor, but plenty of it never reaches the public eye.

Onlinecensorship.org, a project the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Visualizing Impact (and friend of Global Voices) is working to change this by crowd-sourcing reports submitted by users who have had their content removed or accounts suspended on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, Google+ and Instagram.

Users can submit a report if a social media platform removes their posts or suspends their accounts through the onlinecensorship.org reporting tool. The site also explains how users can appeal to Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, Instagram, Flickr, and Google+ the removal of their posts or the suspension of their accounts.

Just last month, the group launched an Arabic version of their website onlinecenorship.org. EFF’s Jillian York who is one of the site’s co-founders (and a Global Voices board member), explained that the recent series of bans on content from Palestine made them expedite the rollout of the website’s Arabic version.

For Onlinecensorship.org, Facebook is the most frequently reported platform. While most reports came from the United States, followed by Canada, York says that by making the website available in other languages they hope to “increase diversity in the data,” and “compare between countries or regions of the world what social media censorship looks like.”

Screenshot of onlinecensorship.org About page.