As a second coronavirus outbreak hits the country, imprisoned women human rights defenders are facing continued ill-treatment as well as new charges designed to prolong their imprisonment.

This statement was originally published on gc4hr.org on 22 June 2020.

The world has been facing a pandemic that left prisoners including human rights defenders and prisoners of conscience very vulnerable among other populations in the Gulf region and neighbouring countries. Since the COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly in March 2020, the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) has been calling for the authorities in the region to release all prisoners who pose no risk to society. GCHR is further concerned by a new trend in Iran of adding sentences to already imprisoned women human rights defenders, leaving them ineligible for furlough during the pandemic.

In Iran, the COVID-19 crisis has quickly taken a second peak as the country’s health infrastructure has been too precarious after years of sanctions, corruption, and the state’s obstinacy towards its international commitments. The Iranian authorities have put the country under strict laws and practices that are built on discrimination, segregation and proscription of women’s rights, while committing mass human rights violations inside and outside the country.

Those who dare to speak against such human rights violations are persecuted and prosecuted with inane and lengthy sentences and become victims of a legal system that flaunts international standards of law. Freedom of expression and assembly in pursuit of gender equality are often regarded as acts against “national security,” “propaganda against the state,” “encouraging and providing for moral corruption and prostitution” and “insulting the sacred.”

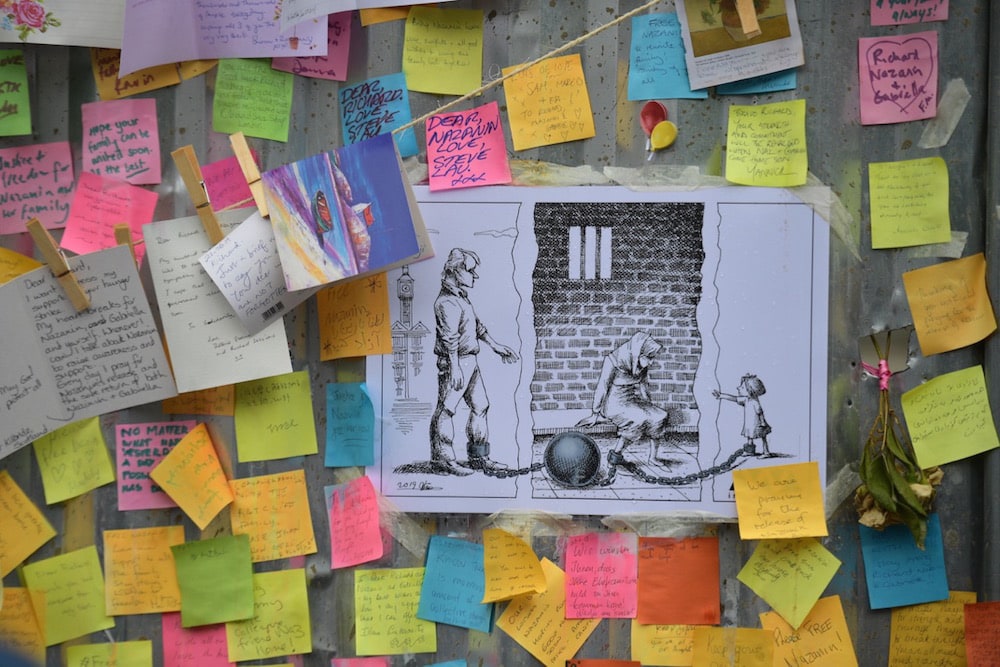

In mid-March 2020, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, a 37-year-old British-Iranian citizen, who has been in prison since 2016 when she was sentenced for five years, was released temporarily from Evin prison in Tehran. While her release has been extended, she remains required to wear an ankle bracelet and not move more than 300 metres from her parents’ home. Her release came following the serious threat of the coronavirus spreading through Iran’s prison system. Zaghari-Ratcliffe went on a water-only hunger strike to protest her continued imprisonment last year, when she was held in solitary confinement for over a month, according to her family.

In light of the COVID-19 risk, the Iranian judiciary said it had so far released 85,000 prisoners, half of whom were political prisoners. Yet, it is still unknown what proportion of women human rights defenders and activists is among those who have been released, or even those who are still in prison.

Among those who remain in prison is journalist and human rights defender Narges Mohammadi, the spokeswoman for the Centre for Human Rights Defenders in Iran, who has been imprisoned since 2015, serving a combined 16-year prison sentence. She was sentenced to 10 years in prison for establishing the Step by Step to Stop Death Penalty group (also known as LEGAM), as well as five years for “gathering and colluding with intent to harm national security,” and one year for “spreading propaganda against the system.” She was sentenced on 17 May 2016 and her sentence was upheld on 28 September 2016. According to the law, she must serve the longest sentence, namely the 10-year sentence. She has been held in Evin prison since 5 May 2015, already serving a previous six-year sentence.

In a ludicrous move that seems all the more cruel considering the COVID-19 threat, Mohammadi is facing new charges, even while in prison, which was revealed in an open letter recently sent by her bother to the Iranian authorities. Mehdi Mohammadi, exiled in Norway, explained in his letter that his sister had serious health problems but “was not allowed out of prison to see a doctor.” In May 2020, human rights groups reported that Mohammadi was facing up to five years more in prison and 74 lashes for various charges including “collusion against the regime,” “propaganda against the regime” and the crime of “insult”.

Also in June 2020, imprisoned woman human rights defender Atena Daemi, who is serving seven years in prison, was charged with “disturbing order” after being accused of chanting anti-government slogans on the anniversary of Iran’s 1979 revolution. She was sentenced to five years in prison in 2016 and in September 2019, a court added two years and one month to her sentence for “insulting” and “disseminating anti-government propaganda” after she wrote an open letter from prison criticising the execution of political prisoners. Daemi’s family says the new charges meant she would no longer be eligible for furlough on 4 July 2020 under the law, nor could she be freed under the current furloughs being offered during the pandemic.

On 1 June 2020, women’s rights activist Saba Kord Afshari was sentenced to 15 years in prison by an appeals court after having been acquitted on 17 March 2020 by the Evin Prosecutor’s Office. She was sentenced for “promoting corruption and prostitution through appearing without a headscarf in public,” for her role in the White Wednesday protest movement against mandatory veiling. Kord Afshari is already serving a nine-year sentence. She’s also ineligible for a furlough during the pandemic.

In April 2020, United Nations human rights experts called on Iran to expand its temporary release of thousands of detainees to include prisoners of conscience and dual and foreign nationals who are still behind bars despite the serious risk of being infected with COVID-19, following concerns raised from inside the country.

Iranian activists’ families have raised concerns over the ill-treatment, the lack of proper hygiene and the inadequate measures taken by the authorities to adapt and mitigate the circumstances linked to the spread of the coronavirus in the Iranian prisons.

GCHR calls on the Iranian authorities to immediately and unconditionally release all women’s rights defenders detained for peacefully practicing their rights to freedom of expression, assembly and calling for gender equality. This is all the more pressing due to the health risks related to the COVID-19 pandemic.