In recent years, free expression groups in the Caribbean have been urging individual nations to repeal criminal defamation laws. What hold do these laws have over the media and others?

Criminal defamation. The term gets thrown around a lot in legal and free expression circles, but what does it really mean? For some, it is a necessary tool for maintaining public order and protecting individuals from smear campaigns or baseless accusations, but for many others it is an instrument that powerful individuals use to silence their critics. Wesley Gibbings, journalist and General Secretary of the Association of Caribbean MediaWorkers (ACM), has pointed out that with the increase of online activity, “the threat of criminal defamation should not only be the concern of journalists, but of all citizens who have a point of view – whether they publish it on their Facebook page or Twitter or any other social media platform”. On the subject of criminal defamation in the Caribbean, Scott Griffen, International Press Institute (IPI) Director of Press Freedom Programmes, told IFEX that “Much of the law on the subject dates back to colonial times, and does not properly serve the needs of democratic society; in parts of the English-speaking Caribbean, versions of mid-nineteenth century English libel law remain in force.” In more recent years, free expression groups in the region have been urging individual nations to repeal criminal defamation laws. How do these laws affect the media and others in the Caribbean?

Keep reading below to find out what criminal defamation is and how it is used in the region, where laws on criminal defamation are being debated and reformed.

What is criminal defamation?

According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, defamation is defined as: “The act of saying false things in order to make people have a bad opinion of someone or something: the act of defaming someone or something”.

In countries that have criminal defamation laws on the books, as opposed to those with only civil defamation laws, people can bring criminal charges against those who they believe have made false statements about them. Whereas civil defamation suits usually result in monetary fines, but not jail times, criminal suits can result in prison sentences and criminal records for those convicted, and often, those people are journalists and others who dare to criticize people in powerful positions. In some countries, criminal defamation is also referred to as criminal libel or slander, depending on whether the language appears in print or is spoken.

In the free expression community, the punishment for criminal defamation is generally considered to be disproportionate. IFEX member ARTICLE 19 campaigns against criminal defamation because they believe it has a “harsh effect on freedom of expression” and the threat of being criminally prosecuted can discourage journalists from publishing information in the public interest. In addition to the threat of imprisonment, individuals and media outlets that are convicted of criminal defamation have also faced hefty fines, and reporters have had their right to practice journalism suspended.

In 2002 a joint declaration by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media and the OAS Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression stated that: “Criminal defamation is not a justifiable restriction on freedom of expression; all criminal defamation laws should be abolished and replaced, where necessary, with appropriate civil defamation laws.”

Why is it such an issue in the Caribbean?

Criminal defamation laws in the Caribbean have been described as holdovers from colonial times. Criminal libel originated in Elizabethan England as a means to silence criticism of the privileged classes.

The IPI and the ACM launched a campaign in 2012 to get the governments of Caribbean nations to decriminalize defamation. At the time, all the independent states in the region had criminal defamation laws on the books. According to Griffen, in addition to repealing these laws, IPI’s campaign is also aimed “at the modernisation of defamation law in general in the region, to meet international standards on freedom of expression.” When they first launched the campaign, IPI felt that repealing the legislation could “happen in short order”. The move was well underway in the region and they felt that they could add their voice to the existing calls for change.

What is the impact of criminal defamation laws in the region?

Criminal defamation laws in the Caribbean have allowed for the prosecution of journalists in many countries, including recent cases in Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Cuba.

In Haiti in 2008 journalist Joseph Guyler C. Delva was sentenced to a month in jail for allegedly defaming a senator. In the same country in 2011, three journalists were charged with defamation by their former employer, who claimed they were waging a smear campaign against him. They faced fines and a three-year jail sentence.

In 2012 in the Dominican Republic, radio journalist Johnny Alberto Salazar was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and fined 1 million pesos (approx. US$22,000) for libeling a lawyer. At the time, Reporters Without Borders said that whether or not Salazar had actually committed libel or not, the punishment under the criminal code was disproportionate. His conviction was later nullified.

Cuban journalist Calixto Ramón Martínez Arias spent seven months in jail after being convicted on criminal defamation charges in late 2012. He was arrested and charged for writing about cholera and dengue outbreaks in the country, even though the government confirmed the epidemics just days after his story was published.

A 2013 report by IPI found that the Surinamese Criminal Code recognised not only libel and slander under the umbrella of defamation, but also insult, which the report’s author Dr. Anthony L. Fargo described as “so vague and vulnerable to abuse that it should be eliminated”. Under the code, individuals in Suriname convicted of contempt toward the government faced up to seven years in prison.

The more subtle effects of these laws, such as the forced silence of those who are afraid to speak out lest they be charged, are harder to calculate. It is impossible to know how many stories have not been reported on out of fear.

What does a future without criminal defamation look like?

The Dominican Republic approved a new penal code in late 2014 that removed prison sentences for defamation; if journalist Johnny Alberto Salazar were convicted of defamation in the Dominican Republic today, he would not spend any time in jail. However, defamation is still considered a crime and is punished with significant fines.

Griffen noted that in terms of awarding damages for having been defamed, IPI is pushing for states to “cap the amount of damages that may be awarded, or at least specify that damages must be proportionate to the harm done and to the financial means of the defendant”.

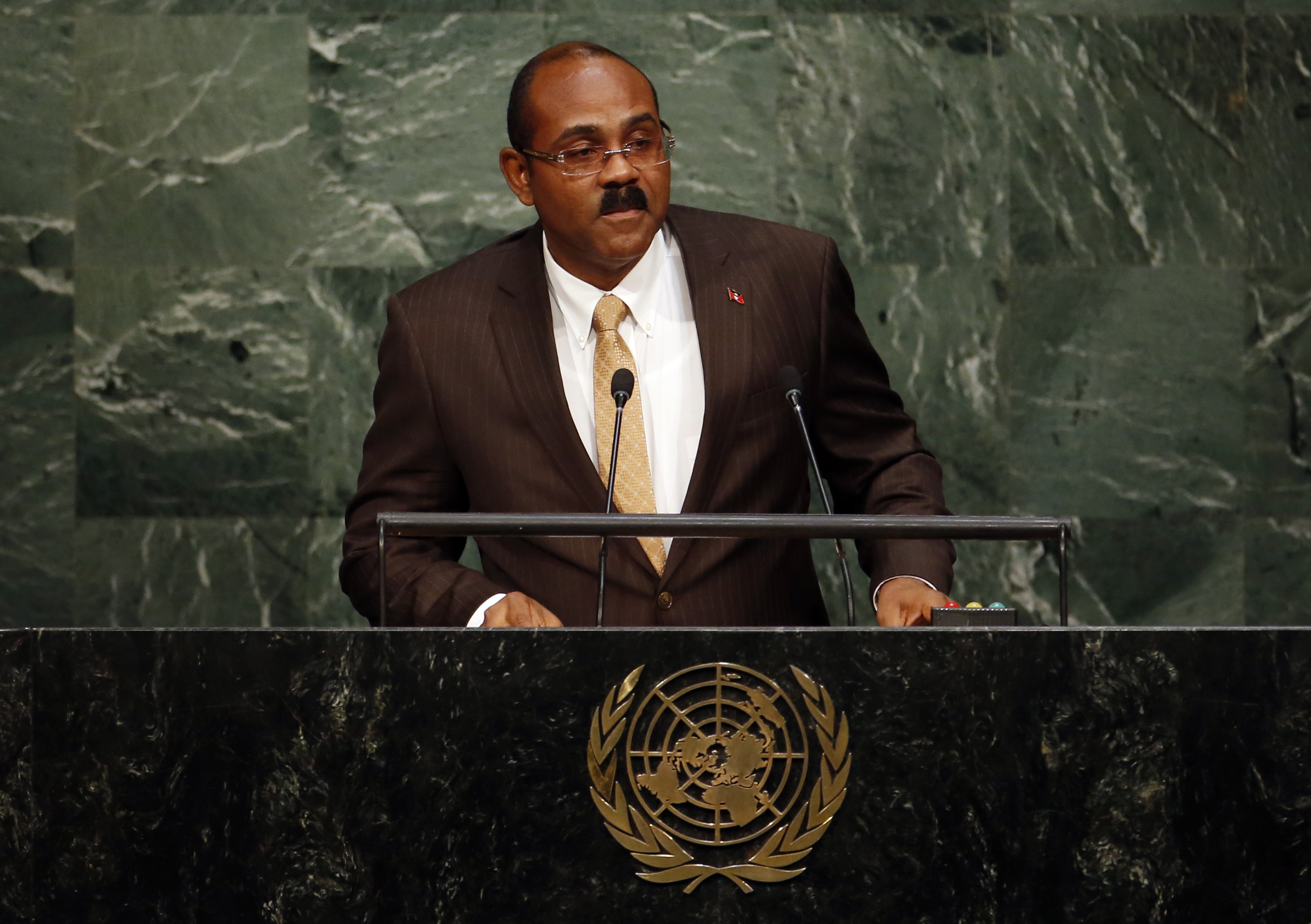

Martina Johnson, a media worker in Antigua and Barbuda, told IFEX in July 2015 that she welcomed her country’s recent move to decriminalise defamation. “Now that the law has been repealed and replaced with the Defamation Act, a person who is sued for defamation would only have to pay damages if the judge finds he or she in fact offended the claimant.”

She went on to say that even though she expects fewer chilling effects on free expression, the new law still carries serious repercussions for those found guilty. She noted that journalists need to continue to do due-diligence when it comes to fact checking and research, because getting rid of criminal defamation laws does not mean that they have carte blanche to write whatever they like.

What still needs to be done?

According to an IPI legal overview of Criminal Defamation laws in the Caribbean, as of February 2015, 14 out of the 16 nations reviewed still had some form of criminal defamation on the books. That number dropped to 13 after Antigua and Barbuda repealed criminal defamation in April 2015, joining Grenada and Jamaica as the third country to have completely decriminalized defamation. Trinidad and Tobago did so partially in early 2014.

But changing these laws can be a slow and challenging process— the government of Antigua and Barbuda being one such example. In April 2013 that country’s government committed to repealing criminal defamation when they met with IPI during a mission to the region. The current Prime Minister promised, and failed, to repeal them within the first 90 days of his administration. Though it took more than two years to make good on the promise, the country now has completely rid itself of criminal defamation.

At a meeting in Port of Spain in 2012, organisations from 10 countries endorsed a declaration calling on governments throughout the Caribbean to repeal criminal defamation and insult laws. However, three years later, it still remains for certain governments of the Caribbean to work with the press and civil society to change their laws. Following the examples of those nations who have paved the way, they must reform their laws so that the threat of criminal charges will no longer be hanging over the heads of journalists and media outlets.

Wikipedia/Kmusser

Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda Gaston Browne, whose government recently repealed criminal defamationREUTERS/Andrew Kelly