The weekly "Semana" has revealed the existence of a DAS instruction manual detailing how to spy on, threaten and discredit NGOs, judges and journalists.

(RSF/IFEX) – The weekly “Semana” has just revealed the existence of an instruction manual for employees of the Administrative Department of Security (DAS), Colombia’s leading intelligence agency, that explains how they should spy on, threaten, intimidate and discredit NGOs, judges and journalists who create problems for the government.

The revelation is the latest in a series of scandals implicating the DAS, coming after phone tapping revelations in February 2009, the discovery in May of a list of media outlets and journalists being kept under surveillance and the disclosure in October that bodyguards assigned to protect journalist Claudia Julieta Duque were in fact spying on her.

“Such methods of surveillance and intimidation are worthy of a police state,” Reporters Without Borders said. “The recent dismissal of senior DAS officials has not resolved the problem of abusive practices within the agency. We note that the president’s office has so far failed to dissociate itself from these latest ones. And why hasn’t the DAS handed over its files on Duque and other journalists to the Constitutional Court, as it is supposed to?”

The national daily “El Espectador” said the spying manual was among the files seized during searches of the DAS offices that were carried out on orders from the National Attorney General’s Office. The manual, which is in the form of a PowerPoint document entitled “Political War”, includes instructions on how to make anonymous telephone calls and spread false allegations.

One of the manual’s most alarming aspects is its use in the case of Duque, the Radio Nizkor reporter whose bodyguards were spying on her for the DAS. The authorities appear to have been worried about Duque’s investigative reporting of the 1999 murder of columnist and humorist Jaime Garzón, which may have been carried out by former DAS employees.

Duque’s personal details, including her telephone numbers and e-mail addresses, appear at the head of the manual, which recommends how long anonymous calls should last, the kind of place from which they should be made and how the person making the call should travel in a bus and avoid places with surveillance cameras. These recommendations appear to have been followed to the letter in Duque’s case since 2004, the year she began receiving calls threatening her and her 10-year-old daughter.

The DAS’s activities have never been properly investigated. The Constitutional Court ordered the DAS to hand over all the information it had gathered on Duque, but the agency has yet to respond.

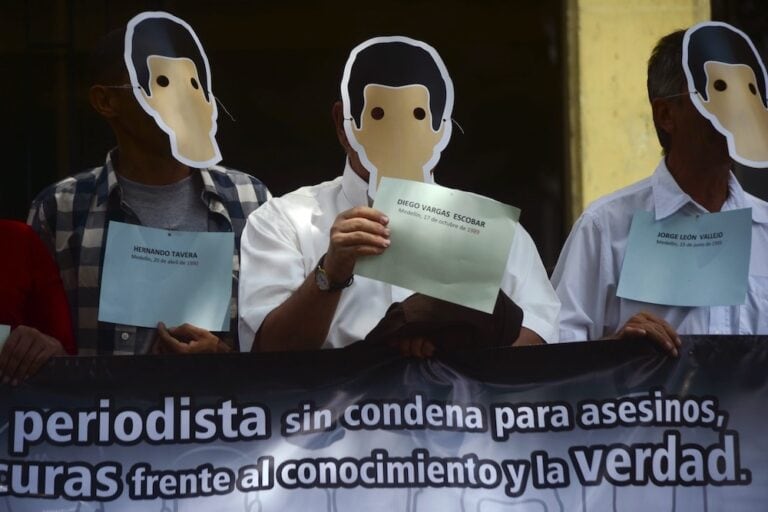

Hollman Morris, who has been covering Colombia’s civil war for more than 10 years and who, like Duque, was one of the first journalists to be targeted by the DAS, has brought a complaint against the Colombian state before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, calling for an investigation into “those responsible for the threats, harassment, tailing, defamation and political stigmatisation” of himself and his family, which forced them to flee the country.

In the 71-page complaint, prepared with the help of the José Alvear Restrepo lawyers collective, Morris said he received the first threats in 2000, when he was working for the daily “El Espectador”. Since then, he has been the target of various forms of harassment, threats and smear campaigns, including by President Alvaro Uribe himself.