If there is anything that stands out from Fundamedios' research on how the media and journalists were impacted in the earthquake, it is the unbeatable will to get back to the task of communicating as soon as possible.

The following is a translation of a statement that was originally published on fundamedios.org on 27 April 2016.

What were you doing at 18:58 on Saturday 16 April? The answers to this question will be quite diverse. But how would you answer ‘what were you doing when the earth stopped shaking’? Certainly, we all reacted in the same way: ensuring that everyone was alright, checking in on our loved ones who were likely doing the same and trying to reach us to let us know what happened.

In Ecuador, more than two hours passed before the national media circulated the news that there had been an earthquake. This information had already been distributed by most of the international news agencies. What was going on during those two hours?

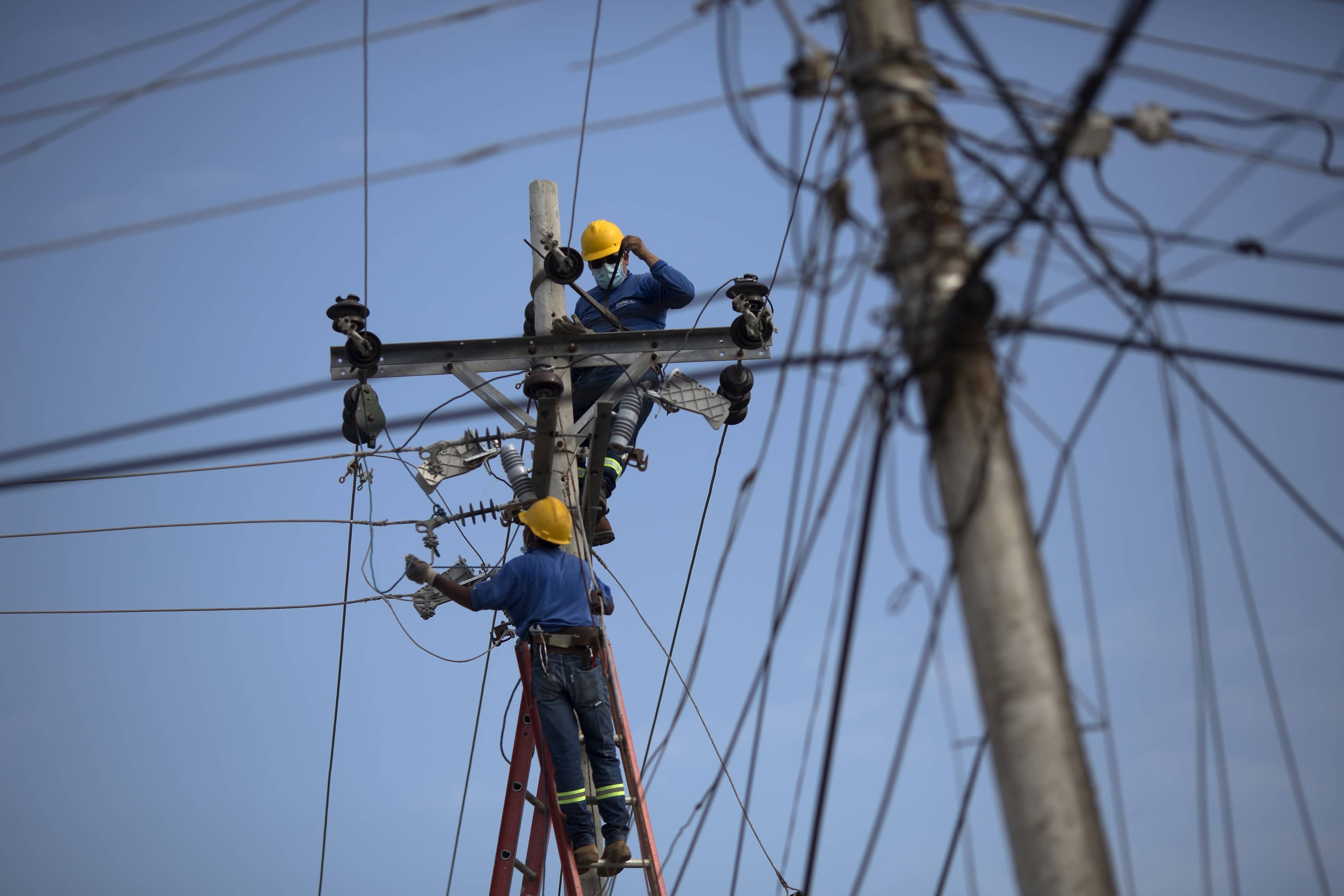

Those minutes, those hours of misinformation, felt like an eternity in the areas where the 7.8 earthquake struck with the most intensity: Muisne, Pedernales, Canoa, Bahía, San Vicente, Chone, Manta and Portoviejo. There was no electricity and therefore no access to the Internet. Mobile phone communication could continue until the phones’ batteries ran out. On the radio there was silence. The local TV channels also stopped broadcasting. There was a quiet, reminiscent of a 1950s style disaster movie.

Except this wasn’t a film and behind the silence tragedy was unfolding. Almost all of the 86 local media outlets in Manabí and Esmeraldas stopped broadcasting. But 14 of those suffered severe damage: their facilities were demolished, some of their employees or their relatives were killed, they suffered irreparable structural damage, or their transmission equipment broke down.

Another 18 media outlets were affected and forced off the air for up to 48 hours from the moment disaster struck.

The initial scenes were marked by darkness, shouts from the victims, the world around them collapsing, desolation and despair. Once this paralysing fear passed one had to face the reality of the situation whose full impact was unknown at that moment. Soon after the earthquake struck, three radio stations and one TV channel began to work together to bring to Manabí residents the little official information that was available at that moment. Depending on a diesel electric generator, one of the stations served as the headquarters; another station could only emit the broadcasting signal, as their studios had been destroyed. The stations did this in coordination with each other, even though they risked a penalty for their actions under the schizophrenic legislation that governs media in Ecuador. On the one hand the Communication Law allows connections between media outlets – however, the Telecommunications Law stipulates that such links can only be established after prior notification to the Agency of Regulation and Control of Telecommunications (Agencia de Regulación y Control de las Telecomunicaciones, Arcotel). “Someone needed to say something, we informed everyone that there was no tsunami warning. We were doing our job, trying to inform people,” explained one of the media outlets.

If there was anything that stands out from Fundamedios’ research on how the media and journalists were impacted in the earthquake, it is the unbeatable will of the media outlets to get back to the task of communicating as soon as possible, undaunted by the challenges that were facing them. These challenges stemmed from the damage incurred by their offices and equipment, but also from the fact that some of their staff lost family members or their property. Fundamedios found that more than 80 members of the media, among them journalists, radio station operators, technicians and others, were directly impacted by the earthquake, either by losing a loved one or having their home destroyed.

The most serious case was in Pedernales, the epicentre of the earthquake. The only two radio stations based in this city, Altamar and Tropical FM, were reduced to rubble. Some of their workers lost everything and now live in shelters.

“Radio Tropical disappeared. I watched the station’s building collapse,” said Jorge Sárchez who worked at the station. The station’s owner, Marcelo Cepeda, lost his wife, daughter and three grandchildren, all of whom were inside the building.

Jorge is now staying in a shelter in El Carmen and is getting by with help from family and friends. He said that of the six employees at the station, he has been impacted the most as his home was completely destroyed when his neighbour’s house collapsed on top of his. He is also a correspondent for El Diario newspaper, but he doesn’t have a computer that he can do his work on.

Altamar, in contrast, is already back on air operating from a makeshift studio set up next to the remains of the station’s former studios. They are using borrowed equipment that was brought from Portoviejo. “We are under the rubble but we are using this slogan: ‘We are not going anywhere, we are staying in Pedernales.’ It really struck a chord because as soon as the radio station was back on the air people were inspired,“ said journalist Aquiles Zambrano.

Other media outlets that suffered serious damage are located in Portoviejo, Manta, Bahía de Caráquez and Chone. Of the 14 that were identified by Fundamedios, six are still off the air due to serious damage to their equipment and infrastructure. Among these is, for example, Bahía Stereo FM that used to operate in a commercial centre that collapsed. Station owner Trajano Velasteguí estimates the losses at around US$10,000, due to the damage to the control panels and the antennas. “We are trying to find some equipment to use temporarily, I am in contact with friends outside the city to ask for their help,” he explained.

Radio Farra, Sono Onda, La Voz del Espíritu Santo de Dios and FB Radio are still off the air but are also looking for equipment they could borrow and new locations from where they can relaunch their transmissions.

At the same time, there were some positive stories coming out of this disaster. Some of the media outlets were able to set up impromptu studios so they could operate or had to rent space. TV Manabita, for example, is broadcasting from the University San Gregorio as their studios were seriously affected. The El Mercurio newspaper remains in circulation with an edition of eight pages (normally it has 32) and is continuing to print even though its printing press was damaged.

In an era of mass global media, social networks that seem to unify people from all over and a massive flow of information that travels the world, the importance of small local media is still immense. It is impossible to imagine how a community can develop without access to local news sources so that people can be informed about their own communities, and a forum where they can share their opinion, oversee and debate the actions of government officials and demand accountability.

In the regions that were impacted by the earthquake, a large number of media outlets have suffered damage and dozens of press workers have lost their jobs, their loved ones or their belongings. On 3 May, World Press Freedom Day, Fundamedios, together with other press and media organisations, will launch a campaign to help these small and medium sized media outlets and their staff. And we also add our voice to the call for assistance for the 27 Ediasa workers who were impacted. El Diario newspaper is published by Ediasa.

The impact on these media outlets and journalists must be taken into consideration, as the State announces its plans for the reconstruction of the decimated zones. For example, will it be possible to continue the conversation about the allocation of 120 broadcasting frequencies in the region when so many media are in this state of disrepair? Could the communications and telecommunications authorities be that indifferent to what is happening?