November 2021 in Europe and Central Asia: A free expression round up produced by IFEX's Regional Editor Cathal Sheerin, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

November saw the EU Parliament formally back a report on measures to tackle SLAPPs. It saw new legislation in Poland restricting journalists’ and rights defenders’ access to the border with Belarus. It also saw women attacked by Turkish police on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and rights defenders express solidarity with Belarus’s political prisoners.

Belarus: “We’ll massacre all the scum”

November saw Belarus’s government continue its crackdown on the independent press and civil society.

Early in the month, the authorities blocked access to the websites of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) and PEN Belarus; they also declared the Belsat TV channel and the BelaPAN news agency ‘extremist formations’.

Around the same time, 35 OSCE states invoked the Vienna Mechanism to demand answers from the Belarusian government on the “serious human rights violations and abuses” that followed the disputed 2020 presidential election. Unsurprisingly, Belarus’s response did “not indicate a material change in the approach of the Belarusian authorities”.

The government’s absolute refusal to change course was further underlined in November during an interview that President Lukashenka gave to the BBC. When questioned about the 270 Belarusian civil society groups that had been forced to close since July 2021, he replied: “We’ll massacre all the scum that you [the West] have been financing”.

So far, Lukashenka’s repression of independent voices has resulted in over 880 political prisoners. Those prisoners were remembered in acts of solidarity around the world on the Day of Solidarity with Belarus’s Political Prisoners (27 November).

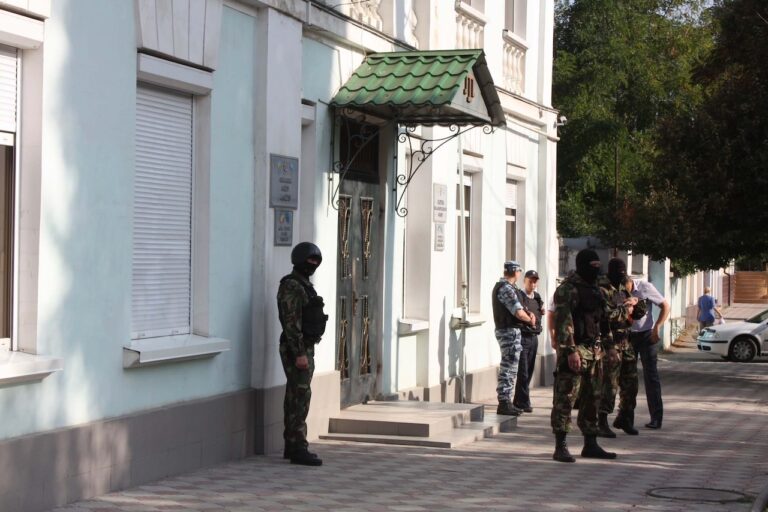

Among these prisoners, according to BAJ’s records, are 30 journalists. Since January 2020, BAJ has documented the detentions of over 580 members of the press. Its latest report (covering January to September 2021), also records more than 140 raids on journalists’ offices and homes, as well as access blocks on over 100 political and media websites.

For more on the persecution of Belarus’s journalists, you can watch a panel discussion organised this month by ARTICLE 19 and the International Press Institute, entitled ‘Reporting against all odds: Journalism in Belarus today [VIDEO]’. Speakers include Teresa Ribeiro, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, and Miklos Haraszti, former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus.

Turkey: “Unprecedented” rise in police brutality

On 26 November, a court in Turkey decided again to continue the unjust detention of civil society leader Osman Kavala. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled in 2019 that Kavala should be released and that all charges against him should be dropped. Rights groups, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have called on the Council of Europe to launch infringement proceedings against Turkey over its continued refusal to abide by the ECtHR decision. The Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers was expected to vote on this at the end of the month.

A report published in November by Expression Interrupted showed an “unprecedented” rise in police brutality towards journalists in Turkey. The period covered by the report (July to September 2021) saw at least 51 journalists attacked or impeded in their work by police officers or members of the public. It’s unlikely to be a coincidence that this increase in police violence occurred during a ban on recording police activities at demonstrations or other events. However, this month saw the welcome suspension of that ban by a Turkish court.

Women’s rights activists are also regularly subjected to police violence in Turkey. Activists who marched in Istanbul to mark the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women were themselves attacked by police using rubber bullets and tear gas.

Rights groups have been raising their concerns about the rise in violence directed at women activists and media workers: earlier this year, a report by the Coalition for Women In Journalism found that Turkey was “the leading country for attacks and threats against women journalists”. Last month, the European Commission’s 2021 Report on Turkey highlighted serious concerns over Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention on violence against women, its undermining of women’s rights generally, and the increase in discriminatory discourse directed at LGBTQI+ people.

Russia: “A tool of reprisals against civil society”

Recent months have seen Russia add more journalists and civil society groups to its list of ‘foreign agents’. November saw some high-profile cases where this law was used – in the words of the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights – as “a tool of reprisals against civil society and human rights defenders”.

Mid-month, journalist Dmitry Muratov and his newspaper Novaya Gazeta were fined because their coverage of two civil society organisations had allegedly failed to note the groups’ status as ‘foreign agents’. Muratov was awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize alongside Philippine journalist Maria Ressa in October.

Towards the end of the month, Memorial, one of Russia’s most prominent civil society organisations, was in court fighting for its very survival as the authorities sought to have it liquidated. The prosecutors allege that the organisation has repeatedly violated the ‘foreign agent’ law by failing to tag some published material with the ‘foreign agent’ label.

SLAPPs and libel tourism

There was welcome news this month when the European Parliament formally adopted a report on the use of SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation). These abusive lawsuits are used by the wealthy and powerful to silence journalists and critical voices by draining them financially and psychologically. The report makes several recommendations including proposals for early dismissals of SLAPPs, sanctions for claimants, the prevention of ‘libel tourism’ (suing a writer for defamation in a foreign jurisdiction where libel laws favour the plaintiff) and an EU directive establishing minimum standards to protect victims.

A popular destination for so-called libel tourists is the UK, where this month author Catherine Belton and her publisher Harper Collins were in court facing two defamation lawsuits in relation to Belton’s book, Putin’s People: How the KGB took back Russia and then took on the West. The lawsuits were brought by Russian businessman Roman Abramovich and the Russian state energy company Rosneft.

Abramovich’s complaint relates to his relationship with Russian president Vladimir Putin. Rosneft’s complaint relates to claims that it participated in the expropriation of Yukos Oil Company, which had been privately owned by businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky. IFEX members and other rights organisations issued a joint statement raising our concerns over the lawsuits, which we argue amount to SLAPPs. After a preliminary court hearing, Rosneft decided to discontinue its claim. Any trial based on Abramovich’s complaints is not expected to take place for at least a year.

In brief

Until recently Kazakhstan’s longest-serving political prisoner, the poet and activist Aron Atabek died on 24 November while being treated for COVID-19 in hospital. He had been released from prison in October on what the authorities said were compassionate grounds. Atabek had served 15 years of an 18-year prison sentence and was due to spend the remaining three under parole-like restrictions.

Atabek was convicted in 2007 on charges related to his role in organising a protest against the demolition of a shanty town, in which a police officer was killed. He always maintained his innocence and even rejected a pardon on the grounds that it would have required him to admit guilt. Atabek’s health declined rapidly in prison and the authorities denied him adequate treatment for various chronic health conditions. He frequently complained that he was tortured and ill-treated, and was sentenced to two years’ solitary confinement in 2012 for writing an article that criticised Kazakhstan’s then-president, the authoritarian Nursultan Nazarbaev. The EU Parliament described Atabek as a political prisoner and called for his release earlier this year.

Disturbingly, it is now a crime to spread ‘fake news’ in Greece. Journalists convicted of publishing or sharing what the authorities claim to be ‘fake news’ that is “capable of causing concern or fear to the public or undermining public confidence in the national economy, the country’s defence capacity or public health,” could face up to five years in prison. The amended legislation does not define ‘fake news’ or what standards will be applied in determining whether something is ‘fake news’.

The humanitarian crisis that is taking place along the border between Belarus and Poland, where thousands of migrants and asylum seekers are trapped in inhuman conditions – with Belarusian border guards violently pushing them into Poland and Polish border guards forcefully and unlawfully pushing them back – made headlines around the world this month, despite a state of emergency in Poland that restricted reporting from the area. Multiple journalists have been subjected to brief detention, judicial harassment and intimidation by Polish soldiers solely for attempting to report from the border zone, and IFEX members have called on the Polish government to lift reporting restrictions at the border. However, on 30 November, President Andrzej Duda signed into law legislation that effectively perpetuates many of the measures imposed by the state of emergency, limiting the access of aid organisations and journalists to the border zone.

The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression raised her concerns over the state-capture of the media in Hungary during her visit to the country in November. Pointing to the forthcoming 2022 parliamentary elections, she underlined the need for free and independent reporting and equitable access to the media for all candidates and parties. She also called on the government to recognise the important contributions made to society by journalists and human rights defenders working on the rights of migrants, refugees and LGBTQI+ people instead of making them the targets of campaigns of hate speech, harassment, or stigmatisation.