Rights groups say sale of surveillance technology to oppressive MENA governments has put activists, journalists, and human rights defenders at risk of harassment, imprisonment, or killing.

This statement was originally published on gc4hr.org on 18 December 2020.

During an event held online on 16 December 2020, a group of NGOs said the sale of surveillance technology to oppressive governments in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region should be halted, because it puts activists at risk of imprisonment and harassment. The event was organised by Access Now, ALQST for Human Rights, Amnesty International, Citizen Lab, the Global Forum for Media Development (GFMD), the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR).

You can watch the video online at the YouTube channels of GFMD or GCHR at youtu.be/IwMbyFI4U2A.

Opening the event, co-moderators Marwa Fatafta of Access Now and Khalid Ibrahim of GCHR discussed the risks to human rights defenders and activists, and the need for a coalition of NGOs to help protect activists. “Surveillance tools put activists at risk of imprisonment, torture and killing,” said Ibrahim, noting the cases of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, whose close contacts were surveilled by the Saudi government before he was murdered in Turkey, and GCHR’s Board member Ahmed Mansoor, who was the target of a notorious hacking attempt using the NSO’s spyware.

Fatafta noted, “Following the Arab Spring, many MENA activists went into exile looking to escape oppressive regimes. However, Governments with deep pockets were still able to use surveillance tech to monitor and target them.”

Abdulaziz Almoayyad of ALQST for Human Rights said spyware has become more complicated and is being used not only against well-known individuals like Jamal Khashoggi but also ordinary citizens commenting on social issues on Twitter. These people, whose names we don’t know, “just disappear.” There have been several cases in the news of hacking of phones of Saudi dissidents abroad.

Almoayyad also mentioned the surveillance of Saudi woman human rights defender Loujain Al-Hathloul, who is being tried in court this week for communicating with people on WhatsApp. He welcomed the idea of a coalition to help combat surveillance and said Saudi activists need this coalition to support them.

Scott Campbell of the UNHRC said the UN has condemned surveillance of human rights defenders through resolutions, and notes that a number of factors such as “a lack of national legislation… contributes to lack of accountability to private sector companies profiting from the sale of technologies.”

Mass interception tools were used during the Arab Spring against activists to scoop up communications, said Bill Marczak of Citizen Lab, but as people started to use encryption, this was followed by spyware like FinFisher and Hacking Team used against Bahraini civil society, including journalists and those involved in an inquiry about human rights violations during the February 2011 popular movement. He also mentioned the well-known case of Ahmed Mansoor, who was targeted by NSO group [an Israeli technology firm] – but fortunately Mansoor was sophisticated enough to recognise the hacking attempt and reported it to colleagues, who were able to help him.

Adam Coogle from Human Rights Watch said “the UAE is really invested in creating infrastructure for the homegrown surveillance industry” (i.e. through Project Raven) that is being used in abusive ways to target US citizens as well as Emiratis, such as Mansoor, as documented by Citizen Lab and Amnesty. It’s really important to document these cases so we can do something about it. Human Rights Watch is also working on pushing for export controls of technology in Europe, because every country in the MENA region is using these tools perniciously. He said lawsuits are also really important by activists, such as Saudis, who are in court.

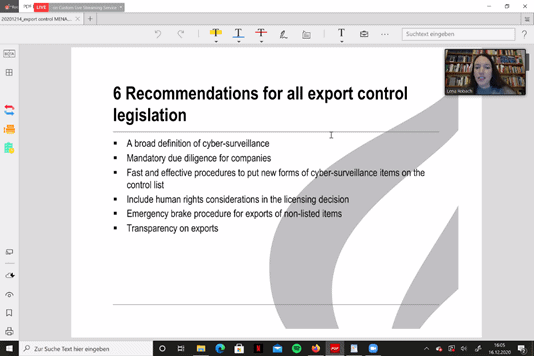

European Union export controls on surveillance tech are needed said Lena Rohrbach of Amnesty Germany, outlining six recommendations for export control legislation, such as mandatory due diligence for companies, including human rights concerns, quickly being able to place new cyber-surveillance tools on export controls lists, and transparency on exports.

In conclusion, GCHR’s Khalid Ibrahim said, “The impact of Covid-19 really is huge on civil society and in communities in the Middle East, such as the Gulf countries,” noting for example that migrant workers are at risk. Location tracking applications are being used for surveillance, in Bahrain for example.

It is a concern in the whole region now with the excuse of Covid-19 to monitor people, including during protests. “That’s why we need a coalition of groups to share resources and look at how we can work together through joint activities, advocacy and research to put an end to the use of surveillance against civil society, which puts our work at risk,” said Ibrahim.

NGOs need to work together to come up with some common goals. Please get in touch with Khalid Ibrahim at GCHR (khalid@gc4hr.org) and Marwa Fatafta at Access Now (marwa@accessnow.org) if you want to join this coalition, which will meet in 2021 to study the issue, set objectives, and organize some activities.