The imprecise, discretionary and hastily-approved Law on Secret Information that the Honduran parliament adopted on 13 January constitutes a major new blow to freedom of information in one of the western hemisphere’s most dangerous countries for news and information providers.

The imprecise, discretionary and hastily-approved Law on Secret Information that the Honduran parliament adopted on 13 January constitutes a major new blow to freedom of information in one of the western hemisphere’s most dangerous countries for news and information providers.

Reporters Without Borders hopes that this law, which turns state-held information into a private reserve, will be overturned on the grounds of unconstitutionality.

“This law strips the Institute for Access to Public Information (IAIP) of all the powers that are the very reason for its existence, namely, determining and justifying the classification of information of public interest,” Reporters Without Borders said.

“These powers have been indiscriminately transferred to each state agency, which will be able to classify information as secret without having to account their decisions. We can only repeat IAIP president Doris Madrid’s objections. How much power will citizens now have for challenging the actions and decisions of public authorities? On the basis of what specific imperative will information be ‘restricted’ under the new law?

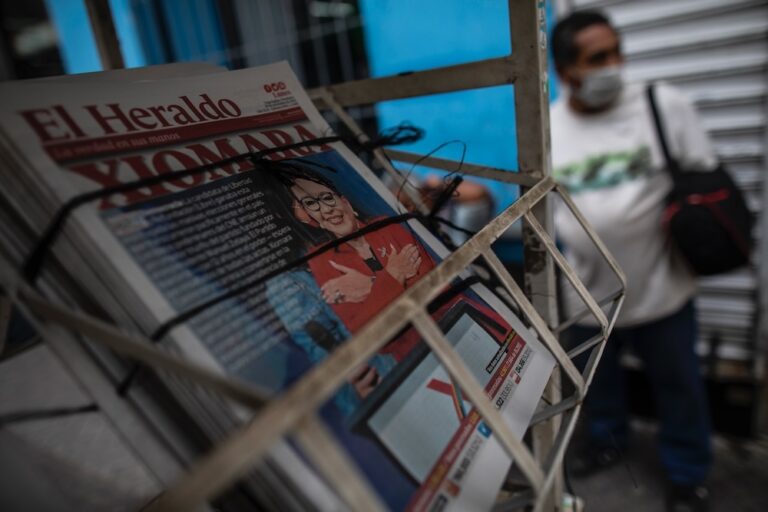

“Even the way this parliamentary initiative was adopted raises questions. Dangerous in content and contrary to international law, including the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights, it is a political disaster coming as it does less than two months after the controversial general elections.”

Submitted to the National Congress by Rodolfo Zelaya, a representative of conservative right National Party, and passed with virtually no debate, the law states:

“Any information, documentation or material relating to the internal strategic framework of state agencies and whose revelation, if made publicly available, could produce undesirable institutional effects on the effective development of state policies or the normal functioning of public sector entities, is restricted. The power to impose this classification lies with the representative of each state entity.”

Valid for five years, a “restricted” classification can be imposed unilaterally by both centralized and decentralized government entities. They also have the power to classify information as “confidential” for ten years in cases of “imminent risk or direct threat to public security and order.”

A third “secret” classification for 15 years can be imposed by the National Defence and Security Council in such cases as possible threats to “constitutional order.” The Honduran president has the power to classify information as “ultrasecret” for 25 years in cases of “direct threat to territorial integrity and sovereignty.”

Honduras is one of the hemisphere’s deadliest countries for journalists, with a total of 38 killed in the past decade, two thirds of them since the June 2009 coup d’état.