The percentage of the world's population living in societies with a fully free press has fallen to its lowest level in over a decade, according to a Freedom House report.

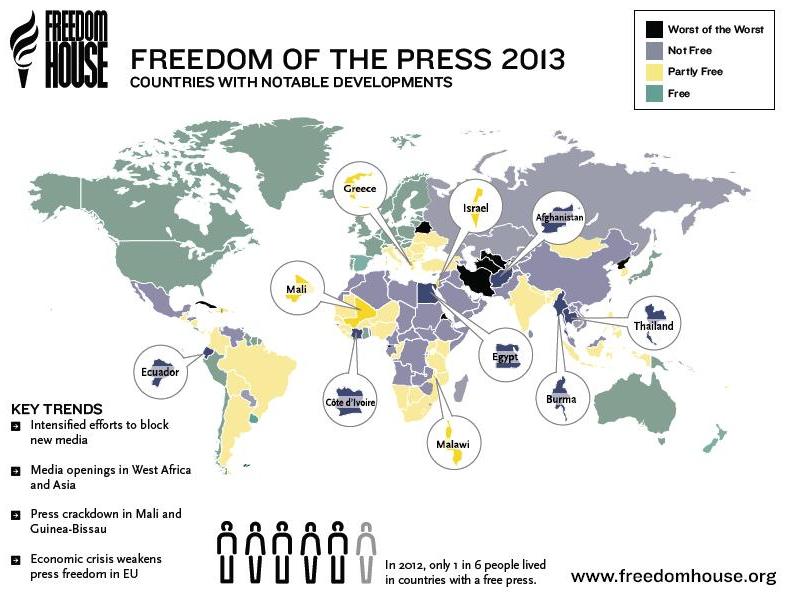

The percentage of the world’s population living in societies with a fully free press has fallen to its lowest level in over a decade, according to a Freedom House report released on 1 May 2013. An overall downturn in global media freedom in 2012 was punctuated by dramatic decline in Mali, deterioration in Greece, and a further tightening of controls in Latin America. Moreover, conditions remained uneven in the Middle East and North Africa, with Tunisia and Libya largely retaining gains from 2011 even as Egypt experienced significant backsliding.

The report, Freedom of the Press 2013, found that despite positive developments in Burma, the Caucasus, parts of West Africa, and elsewhere, the dominant trend was one of setbacks in a range of political settings. Reasons for decline included the increasingly sophisticated repression of independent journalism and new media by authoritarian regimes; the ripple effects of the European economic crisis and longer-term challenges to the financial sustainability of print media; and ongoing threats from nonstate actors such as radical Islamists and organized crime groups.

“Two years after the uprisings in the Middle East, we continue to see heightened efforts by authoritarian governments around the world to put a stranglehold on open political dialogue, both online and offline,” said David J. Kramer, president of Freedom House. “The overall decline is also a disturbing indicator of the state of democracy globally and underlines the critical need for vigilance in promoting and protecting independent journalism.”

Worrying deterioration was noted in Ecuador, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Paraguay, and Thailand – which were all downgraded to the Not Free category – as well as in Cambodia, Kazakhstan, and the Maldives. Meanwhile, Mali suffered the index’s largest single-year decline in a decade due to a coup and the takeover of the northern half of the country by Islamist militants, and media in Greece came under a range of pressures as a result of the European economic crisis. The score declines in those two countries triggered a status change to Partly Free, as did a smaller negative shift in Israel.

Independent media continued to face severe challenges in a number of environments that were already rated Not Free. Influential authoritarian states such as China and Russia used a variety of techniques to maintain a tight grip on traditional media – including detaining, jailing, or bringing legal charges against critics, and closing down or otherwise censoring outlets – even as they expanded their attempts to control content online.

Of the 197 countries and territories assessed during 2012, a total of 63 (32 percent) were rated Free, 70 (36 percent) were rated Partly Free, and 64 (32 percent) were rated Not Free. The analysis found that less than 14 percent of the world’s inhabitants lived in countries with a Free press, while 43 percent had a Partly Free press and 43 percent lived in Not Free environments.

The world’s eight worst-rated countries are Belarus, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. In these states, independent media are either nonexistent or barely able to operate, the press acts as a mouthpiece for the regime, citizens’ access to unbiased information is severely limited, and dissent is crushed through imprisonment, torture, and other forms of repression.

“Government attacks on journalists, both legal and physical, are often what make the headlines. However, there are a number of less prominent but equally sinister factors behind the erosion of press freedom worldwide. These include the devastating impact of shrinking national economies on struggling independent media outlets, and the activities of nonstate actors with a strong interest in muzzling the press, such as drug traffickers and terrorist groups,” said Karin Karlekar, project director of Freedom of the Press.

The report noted several key trends in 2012, including the following:

* New media were subject to heightened contestation, as citizen journalists’ use of unorthodox tools – including microblogs, online social networks, mobile telephones, and other information and communication technologies (ICTs) – to expand the flow of news and information has been met with equally determined efforts by a range of governments to restrict such activity. Repressive measures included the passage or intensified use of new cybercrime laws; jailing of bloggers; and blocks on web-based content and text-messaging services during periods of political upheaval.

* The crucial role played by media in ensuring free and fair elections was apparent in a number of settings. Political contests in countries including Russia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Ukraine demonstrated that a level electoral playing field is impossible when the government is able to use its control over broadcast media to skew coverage, and ultimately votes, in its favor. By contrast, more balanced and open media coverage prior to electoral contests in Armenia and Georgia helped lead to gains for opposition parties and, in Georgia, a peaceful transfer of power.

* West Africa as a whole continued to produce improved environments for media, despite the notable declines in Mali and Guinea-Bissau. A number of the gains took place in countries – such as Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal – where new governments demonstrated greater respect for press freedom and engaged in less legal and physical harassment of journalists than their predecessors. Increased media diversity, including an array of private broadcasters that are able to express critical opinions, was apparent in Liberia and Mauritania. These changes made the subregion a relative bright spot during the year.

* Economic factors are negatively affecting media freedom in a number of democracies. Staff cutbacks and the closure of press outlets have reduced the diversity of content and damaged the media’s ability to perform their watchdog role and keep citizens adequately informed. The problems that emerged in Southern Europe in 2012, particularly in Greece and Spain, come on top of financial pressures that were already plaguing press outlets in the Baltic states and elsewhere in Europe.

Key Regional Findings:

The Americas: The region experienced a decline in press freedom in 2012, with Ecuador and Paraguay falling into the Not Free category and erosion also noted in Argentina and Brazil. The media environment remained extremely restrictive in Cuba and Venezuela, and Mexico continued to be one of world’s most dangerous places for journalists, with high levels of violence and impunity for crimes against media workers, though positive legislation to address this issue was passed in 2012. The United States is still among the stronger performers in the region, but the limited willingness of high-level government officials to provide access and information to members of the press was noted as a concern.

Asia-Pacific: This region is home to one of the world’s worst-rated countries, North Korea, and the world’s largest Not Free setting, China. However, the regional average score improved in 2012. Burma earned the year’s largest numerical improvement worldwide due to broad openings in the media environment, and Afghanistan also registered gains. Less positively, Thailand moved back into the Not Free category, and deterioration was noted in Cambodia, Hong Kong, the Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

Central and Eastern Europe/Eurasia: A modest overall reduction in press freedom occurred in this region during 2012, with deterioration in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan offset by improvements in Armenia and Georgia. Restrictive conditions persist in Russia, where the relatively unfettered new media, which have somewhat mitigated the government’s near-complete control over major broadcast outlets, faced the threat of further curbs during the year. Hungary’s score remained steady amid ongoing concerns regarding extensive legislative and regulatory changes that have tightened government control of the media.

Middle East and North Africa: This region’s level of media freedom remained the worst in the world in 2012, and stasis or backsliding was noted in the vast majority of countries, with the exception of Yemen. While two of the Arab Spring countries, Libya and Tunisia, largely retained their significant gains from the previous year, Egypt moved back into the Not Free category. On the Arabian Peninsula, deterioration was noted in Bahrain, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates. Israel, an outlier in the region due to its traditionally free and diverse press, nevertheless experienced several challenges during 2012, resulting in a status downgrade to Partly Free.

Sub-Saharan Africa: The region suffered a modest decline in press freedom in 2012, largely as a result of the losses in Mali, now rated Partly Free, and Guinea-Bissau, which slid into the Not Free category. However, trends elsewhere on the continent were positive, with significant improvements for Côte d’Ivoire and Malawi and smaller positive moves for Liberia, Mauritania, Senegal, and Zimbabwe. South Africa’s score deteriorated slightly due to de facto restrictions on media coverage of wildcat mining strikes in August and September, and the advancement of the controversial Protection of State Information Bill remained an issue of concern.

The region has consistently boasted the highest level of press freedom worldwide, but its average score underwent an unprecedented decline in 2012. Conditions for the press in Greece deteriorated significantly, moving the country into the Partly Free category, while lesser slippage was noted in Spain, also as a result of the European economic crisis. Turkey, a regional outlier, continued to elicit concern due to its high number of imprisoned journalists.