Journalists' investigations of political issues, corruption, and organized crime in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Honduras accounted for 139 murders of media professionals during 2011-2020. Half of these journalists had received threats related to their work.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 13 May 2021.

Journalists’ investigations of political issues, corruption, and organized crime in small and medium-sized cities in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Honduras account for 139 murders of media professionals during 2011-2020, a study by Reporters Without Borders shows. Half of these journalists had received threats related to their work.

In the framework of “In Danger: Analysis of Journalist Protection Programs in Latin America,” a UNESCO-supported project, RSF analysed the major methods by which journalists were murdered in order to better understand the challenges that media protection programs must take into account. RSF based the study on information from its Barometer, which reports major attacks on journalists worldwide (see note on methodology below).

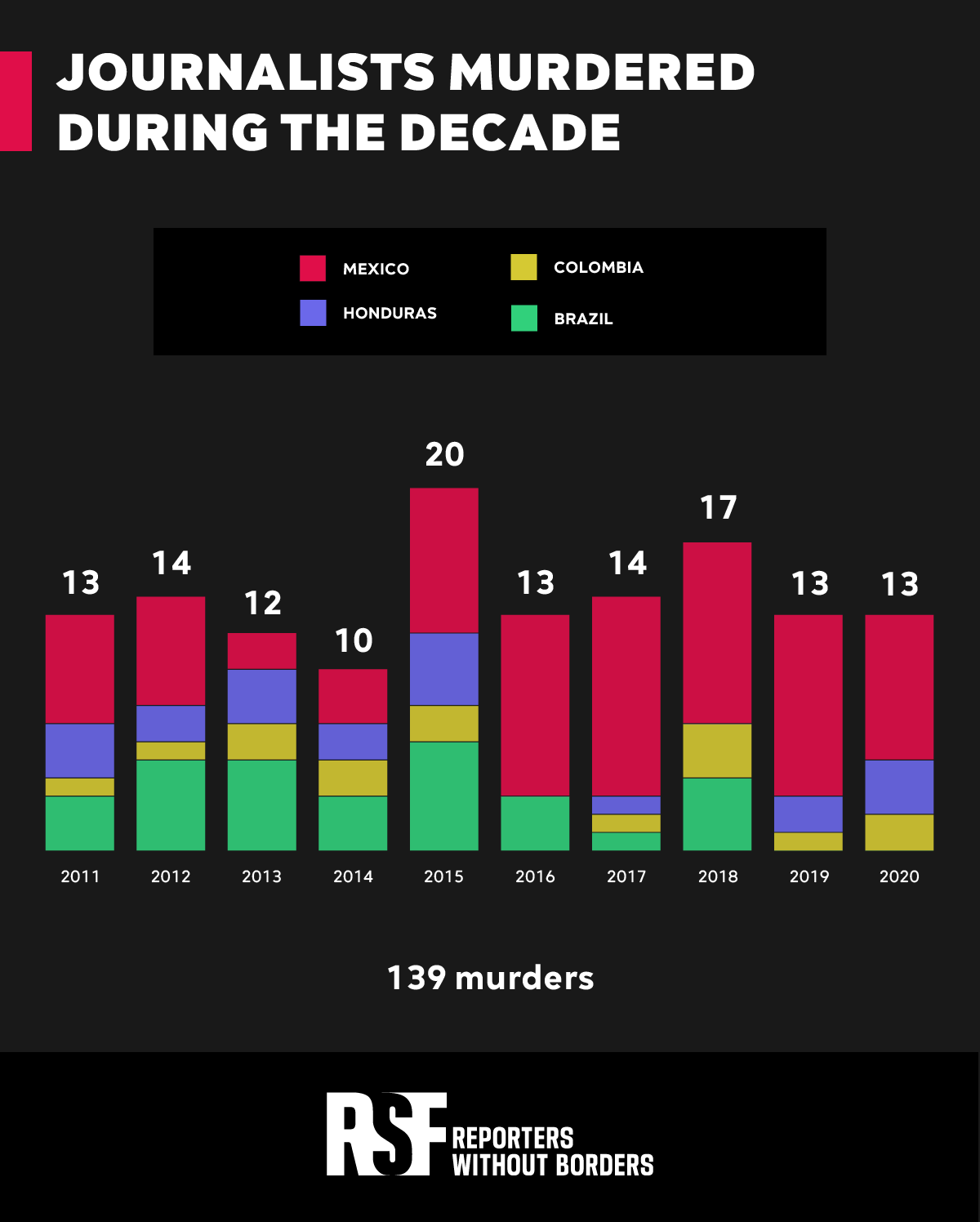

In 2020, Latin America was the region with the greatest number of journalists killed for practising their profession. Taken together, four countries account for 80 per cent of journalists’ murders committed in this part of the world during the 10-year period. In that timeframe, 139 journalists and media workers were killed in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Honduras, according to data collected by RSF.

Data analysis was carried out in partnership with Volt Data Lab, which produced the graphics that illustrate this publication.

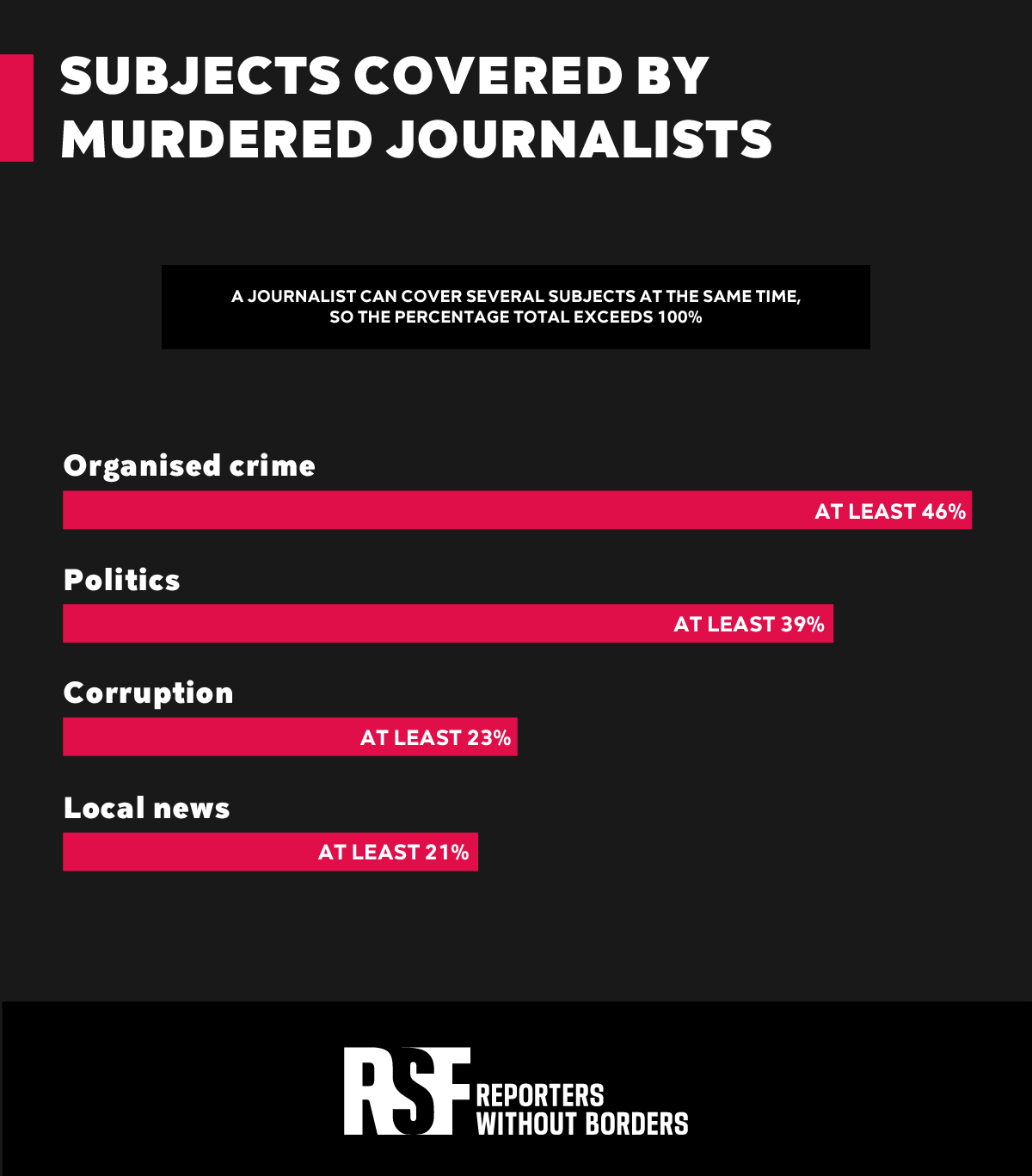

Fifty per cent of the murdered journalists were working as reporters, photojournalists or cameramen, contributing to at least one news organization. An analysis of the RSF data also shows that 39 per cent of the victims covered topics with a political connection. Other issues most frequently covered by the murdered journalists were crime and corruption. Journalists most often targeted were those working in the field, reporting on and criticising illegal schemes in their regions.

Programmed executions

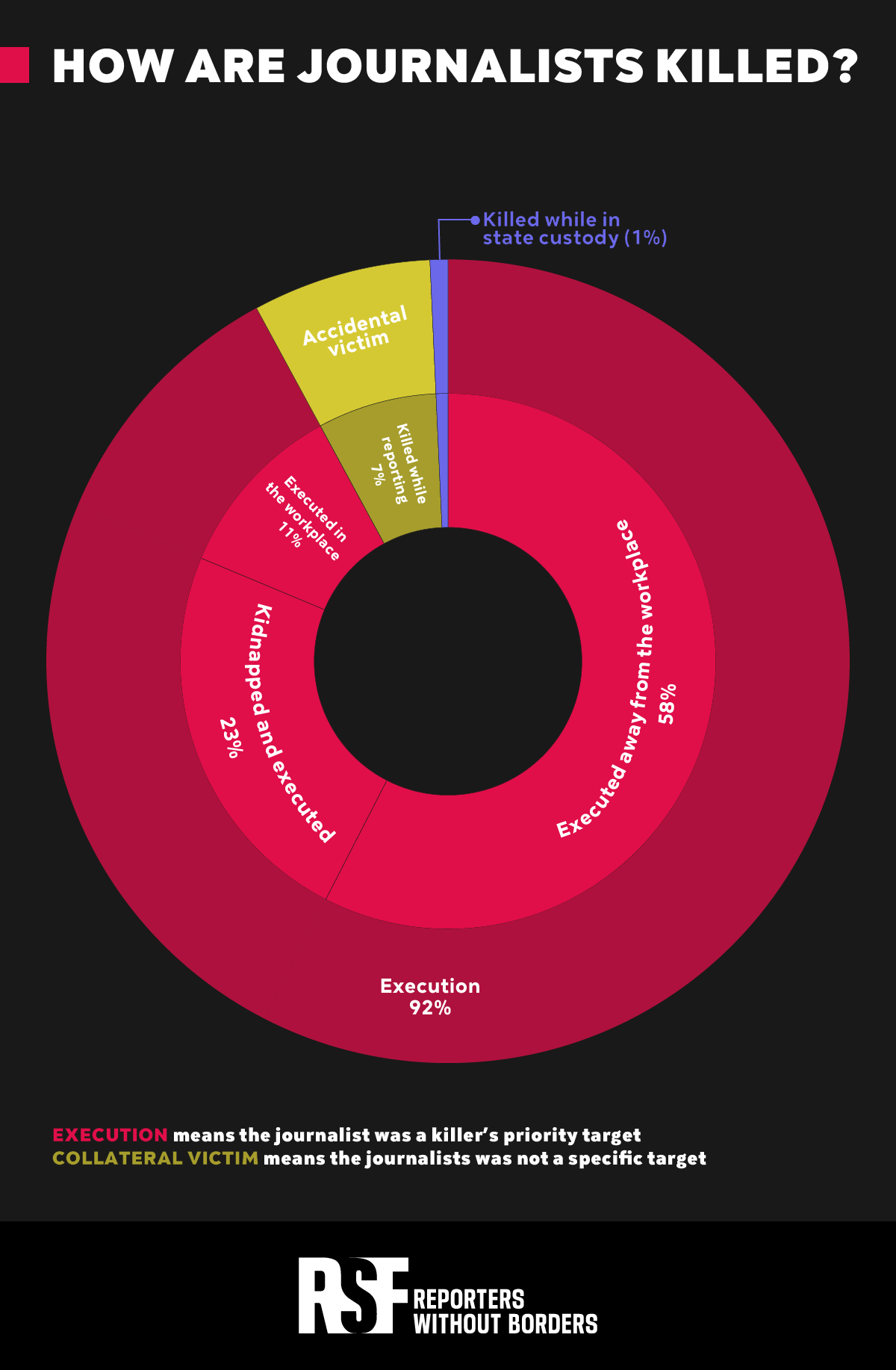

The study deliberately uses the term “target” because, in 92 per cent of cases, evidence showed that the attackers deliberately focused on a specific journalist. Of all deaths recorded in 2011-2020, only 7.2 per cent (10 of 139 cases) occurred in the course of dangerous assignments, when a journalist may not have been killed intentionally.

Some of the journalists were killed in their workplaces, while in newsrooms, or studios. But most (58 per cent) were attacked near their homes, or while traveling between home and work. The details of the great number of these crimes were also often identical: The journalists were tracked by their attackers, and the killings were clearly mapped out by professional hitmen.

Most of the victims were men, living in small cities

The majority (93 per cent) of the victims were men. This should not lead to the conclusion that women journalists in the region are better protected. In the region as a while, where 41 percent of reporters are women, these journalists are also reduced to silence by violent threat campaigns and harassment, generally online, directed at them and their families. At times these campaigns are run by local political bosses.

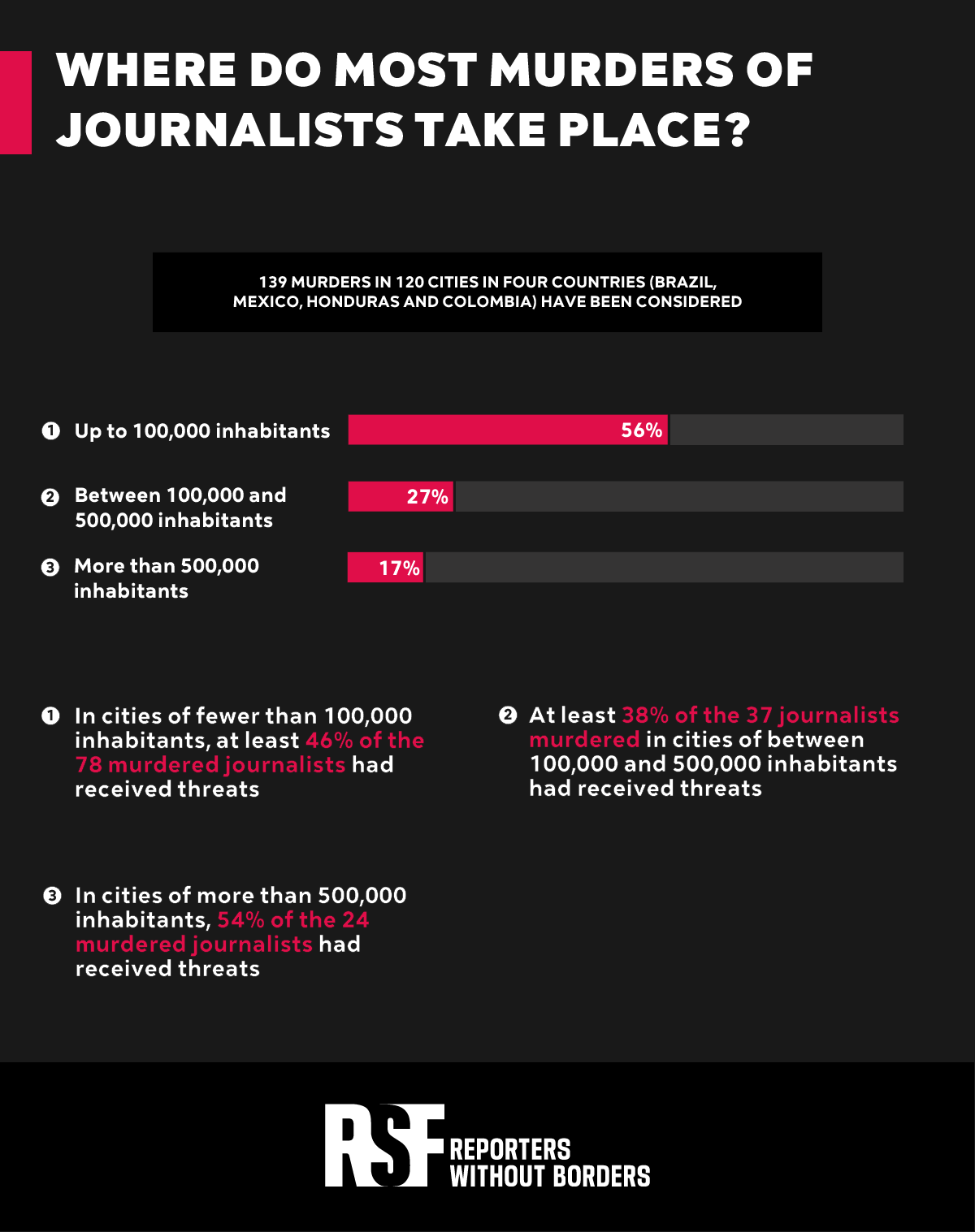

The RSF study also shows that risks are greater for journalists who work in small cities. Of those who were killed, 56 per cent lived in cities with populations of less than 100,000. And at least 54 per cent of journalists killed in cities with populations of 100,000 to 500,000 – medium-sized municipalities in Brazil, Mexico and Colombia – had already received threats before they were murdered.

The statistics do not fit the popular image of an investigative journalist who works for a major newspaper based in a capital city, who is killed for having reported information of national importance. To the contrary, most of the journalists murdered in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Honduras in 2011-2020 lived far from major urban centres, often worked in precarious economic circumstances, contributing to several media organisations, and covered issues that directly affected local officials and inhabitants.

More effective protection programmes urgently needed

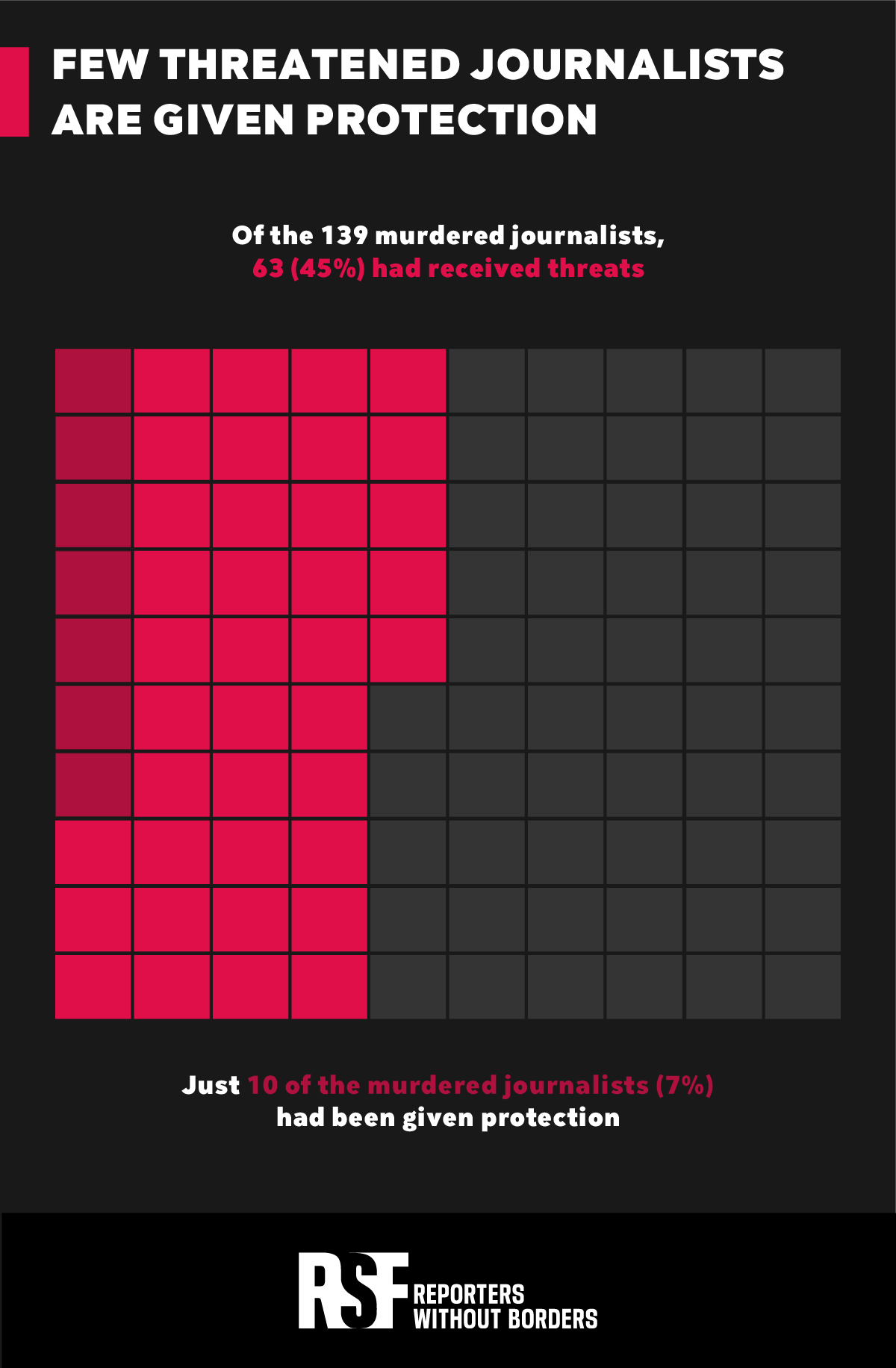

Another conclusion to be drawn from the RSF study is that many of the killings could have been prevented. At least 45 per cent of the victims* had reported receiving threats and had made them public – either in the media they worked for, on their social network accounts, or directly to local security forces.

However, only 10 of the 139 murdered journalists – none of them women – received government protection. This number represents 7.2 percent of total victims, and nearly 16 per cent of those who had received threats. These data pose the question of why only a minority of murdered journalists had received protection, and why the 10 journalists who did receive protection were murdered.

Although Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Honduras are not officially at war, the statistics are cause for great concern. At the end of 2020, RSF’s annual Round-up showed that Mexico was the most dangerous country in the world for journalists, with at least eight journalists murdered. The killings, often carried out savagely, targeted reporters because they had investigated links between organized crime and member of the political class.

Structural violence

Murder of journalists, the most extreme form of censorship, is only the most visible part of anti-press violence. This practice takes place within a larger regional context of permanent threat and structural violence. Human rights advocates and all those who condemn the powers that be, whether in politics or criminal organisations, are affected in systematic form.

When a country is the scene of structural violence against the press, individual journalists’ freedom of expression is not the only issue at stake. The entire society’s collective right to be informed is also affected. In the words of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: “Journalism can only be freely practiced when those who do so are not victims of threats or physical, psychological, or moral attacks or other acts of harassment.”

Journalists have been reduced to silence because the political and public safety environment in their region does not guarantee conditions in which they can practise their profession safely. In addition, most of the media organisations for which they work are too economically strained to protect them. And 10 per cent of them are independent journalists or contributors to community radio stations.

One of the goals of “In Danger,” a project that has received UNESCO support, is to understand how national journalist protection policies can change this grim reality. The project aims to evaluate the operation and effectiveness of journalist protection mechanisms in the four countries in question. Acting on the principle that governments are responsible for guaranteeing conditions allowing the free and safe practice of journalism, RSF will present a detailed report to public authorities that includes strategic recommendations designed to contribute to the consolidation of these measures.