(RSF/IFEX) – The following is a 23 March 2000 RSF press release: Peru General election: 9 April 2000 RSF condemns pressure on television channels and the danger that the biggest Peruvian daily may come under government control Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) has drawn attention to the bias Peruvian television channels are showing towards President Alberto […]

(RSF/IFEX) – The following is a 23 March 2000 RSF press release:

Peru

General election: 9 April 2000

RSF condemns pressure on television channels and the danger that the biggest Peruvian daily may come under government control

Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) has drawn attention to the bias Peruvian television channels are showing towards President Alberto Fujimori in the campaign prior to presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for 9 April. In separate letters to Eduardo Stein, head of the team of observers sent by the Organisation of American States (OAS) to monitor the elections, and Luis Núñez, chairman of the Carter Centre, another group with observer status, RSF also highlighted the threat that the privately owned daily “El Comercio” might come under the control of people close to the government. The organisation called on official observers to take note of press freedom problems in the country when drafting their conclusions about the election campaign. RSF also asked Eduardo Stein to recommend OAS sanctions against Peru if the government did not take specific steps to guarantee the independence of the media.

On 12 March, the programme Contrapunto which is broadcast by Frecuencia Latina, reported that allegations were made against “El Comercio” by Luís García Miro, a former shareholder and director of the daily. He accused the newspaper of harming the Peruvian state through the mismanagement of funds in 1990. He also claimed that his shares in the company were sold against his will in 1994, and that he had never received the promised redundancy payment. Luís García Miro is demanding 20 million dollars (euros) in damages from the daily. A few days earlier, “El Comercio” had reported that over half the two million signatures collected in support of Alberto Fujimori’s candidacy were fakes, and accused several members of the political coalition that supports the president of involvement in the fraud. The Miro Quisada family, which owns “El Comercio”, believes there are “enough indications to suggest that the daily may come under government control”. RSF is reminded of the methods used in 1997 against Baruch Ivcher, who owned a majority stake in Frecuencia Latina. Steps were taken to shift control of the channel to minority shareholders after Frecuencia Latina made allegations against the Peruvian intelligence agency (Servicio de Inteligencia Nacional – SIN). Since then, the channel has maintained a firm pro-government line.

Until the end of February, the seven broadcast channels refused to accept advertisements for opposition parties. According to the organisation Transparencia, at the end of 1999 the same channels devoted 76% of their political programmes to Fujimori – compared to 24% for all the opposition parties. Although the trend was reversed at the start of the year – 65% for the opposition compared to 35% for Fujimori – the channels’ “lack of objectivity” and obvious support for the president has been condemned by several international observers in Peru. The observers said the decision on 29 February to force channels to devote a quarter of an hour of airtime to programmes about the various political parties was “insufficient”.

Television under state control?

Television, which reaches 80% of Peruvians, is by far the most popular news source in the country. The lack of objectivity shown by most channels could be due to government pressure such as the granting or withholding of official advertising, the allocation of broadcasting frequencies or the threat of legal proceedings.

Media owners risk losing control of their channels as the result of court decisions. Since 1997, two bosses have been stripped of their authority after criticising the government or the SIN’s methods. In September 1997, a ruling by the Lima high court permanently deprived Baruch Ivcher of his stake in Frecuencia Latina by stripping him of his Peruvian citizenship. In December 1999 a warrant was issued for the arrest of Genaro Delgado Parker, head of the Red Global channel. He was accused of embezzlement after claiming that the government was controlling the content of television newscasts by using advertising as a means of blackmail. Two months later the transmitters of Radio 1160 were seized on the orders of a court. The station had begun broadcasting a programme presented by César Hildebrandt, who is known for his criticism of the government. On 13 March, in an unprecedented move, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights called on the Peruvian authorities to give back the station’s equipment and to restore the running of Red Global to Genaro Delgado Parker.

Today three of the seven channels are run by people appointed by the legal authorities and a fourth is currently facing trial. Of the three others, one is publicly owned and another belongs to Domingo Palermo, a former minister in the Fujimori government.

Jorge Santistevan, Peru’s “defender of the people”, has said that official advertising makes up more than two-thirds (69%) of all advertising in cash terms. According to the National Advertisers’ Association (Asociacion Nacional de los Anunciantes del Perú – ADAN), the biggest source of official advertising is the president’s office. The granting of television frequencies, which the government may decide to withdraw without warning, is another source of pressure on the media.

Threats to newspapers

The recent attacks on “El Comercio” could mark a new stage in the erosion of press freedom in Peru. Up until now the daily, the oldest and most respected in the country because of its moderate line and support for the middle ground in politics, had been spared any serious harassment. The main threats were aimed at the opposition press.

In October 1999 the opposition daily “Referendum” was forced to close down. Editor Fernando Viaña blamed pressure from the tax authorities. Six weeks later, the daily resumed publication under a new name, “Liberacion”, while “Referendum” resurfaced with a strongly pro-government line. On 21 December police tried to seize equipment from the new daily’s printing works.

A week earlier, “Liberacion” had accused presidential adviser and SIN director Vladimiro Montesinos of illegal acquisition of wealth. The daily had also spoken out against Alberto Fujimori’s decision to stand for a further term as president.

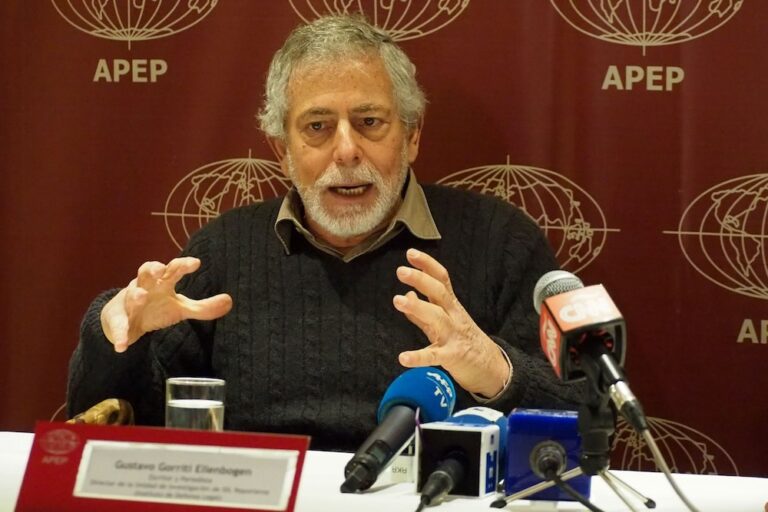

For the past two years Peru’s leading opposition daily, “La República”, has been the target of repeated attacks in the tabloid newspapers which even some of the tabloids’ own journalists admit are controlled by the SIN. Since 1998 Gustavo Mohme, editor of the daily and an opposition member of parliament, has often been described as a “conspirator”, “homosexual” or “arms dealer” by the ten of so dailies of this prensa amarilla (yellow press), which has also accused him of being close to armed organisations such as the Shining Path and the MRTA. Ángel Páez and Edmundo Cruz, investigative journalists with La República, were described as “traitors to the fatherland” and “fanatics of the anti-Peruvian press”, and received death threats. On 27 October 1999 Hugo Borjas, who had run the “society” column of one of the tabloids, “El Chato”, was attacked after he revealed that the daily was being paid by a person close to the government to publish defamatory or insulting reports.

How the secret service is involved

In May 1999 Santiago Canton, the OAS special rapporteur on freedom of speech, said he was worried about a SIN plot against the media known as the “Octavio Plan”. The operation was reportedly launched in 1996 to counter the “threat” to national security from journalists investigating the methods used by the army. Details of the plan reported by the media confirmed the information collected by Reporters Sans Frontières in 1997 and 1998 about pressure on about 15 investigative journalists: phone-tapping, threats of legal action, death threats and so on. In June 1998 Alberto Fujimori publicly promised to open inquiries into the allegations, but the findings have never been made public.

Many observers agree that the Octavio Plan has gradually been turned into a government attempt to keep tabs on the media to make sure that President Fujimori is re-elected. The latest events provide further evidence of this. Hugo Guerra Arteaga of “El Comercio” said that the phone-tapping, which was exposed in 1997, was still going on. Furthermore, the tabloids’ attacks on opposition journalists are now appearing on web sites. Five journalists are on a blacklist of Peruvian personalities listed on a site put online by Aprodev, a mysterious organisation whose director is said to have connections with the SIN.

Courts that answer to the state

Peruvian journalists can no longer rely on the courts to protect them from attack. The independence of the legal system has been jeopardised since the government started appointing “temporary judges” in 1992. In May 1999 two judges who had agreed to investigate a complaint filed by seven journalists known for their reporting on the SIN were “moved to other duties”. On 9 July 1999 the Fujimori government decided to stop recognising the competence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, thus depriving Peruvians of the right to appeal to an international legal authority. The decision, which the court itself described as “unacceptable”, came as it was due to examine Baruch Ivcher’s complaint against the Peruvian government.