Reporters Without Borders (RSF) provides a quantified assessment of press freedom violations in 2020 and looks back at some of the most significant episodes in a year in which constant harassment by President Bolsonaro and his immediate circle poisoned the environment for journalists.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 25 January 2021.

In the latest of its series of reports on attacks against the media under President Jair Bolsonaro, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) provides a quantified assessment of press freedom violations in 2020 and looks back at some of the most significant episodes in a year in which constant harassment by the president and his immediate circle poisoned the environment for journalists.

Some media outlets are “worse than garbage because garbage is recyclable.” This was one of President Bolsonaro’s first verbal sallies against the press in 2021. The press was “good for nothing” and offered nothing but “constant rumours and lies,” he added. Amid increasingly bad news about the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact in Brazil, where the death toll has passed 210,000, the president opted to attack and scapegoat the media.

On 5 January, at one of his first public appearances in 2021, Bolsonaro said: “The country is bankrupt, there is nothing I can do (…) I wanted to change the tax cut scale, but we have this virus that has been fuelled by the press, this useless press.” During an appearance broadcast live on the presidential Facebook account two days later, he again attacked two of his favourite targets, the Globo media group and the Folha de São Paulo newspaper, and added: “The press is responsible for the panic in the country and the loss of lives during the pandemic, a national disgrace.”

In these comments, made at the mid-point of his four-year presidential term, Bolsonaro seems to have set the tone for the coming year. But the hostility is not new, and reflects the way that he, his family and his immediate circle have, in the past year, refined a set of practices designed to discredit the media and silence critical and independent journalists, who they regard as enemies of the state.

In this quantified assessment, RSF completes its series of quarterly reports analysing the coordinated attacks against journalists by the so-called “Bolsonaro system” – see the previous reports here (1) (2) and (3) – and looks back at some of the most remarkable episodes of the past year.

Attacks in 4th quarter of 2020

RSF registered 131 attacks against the media during the last quarter of 2020, which saw municipal elections in 26 of the country’s states (see RSF’s recommendations to the new mayors and municipal councillors).

Total attacks of the “Bolsonaro system” against the press during the third quarter of 2020 (RSF figures)

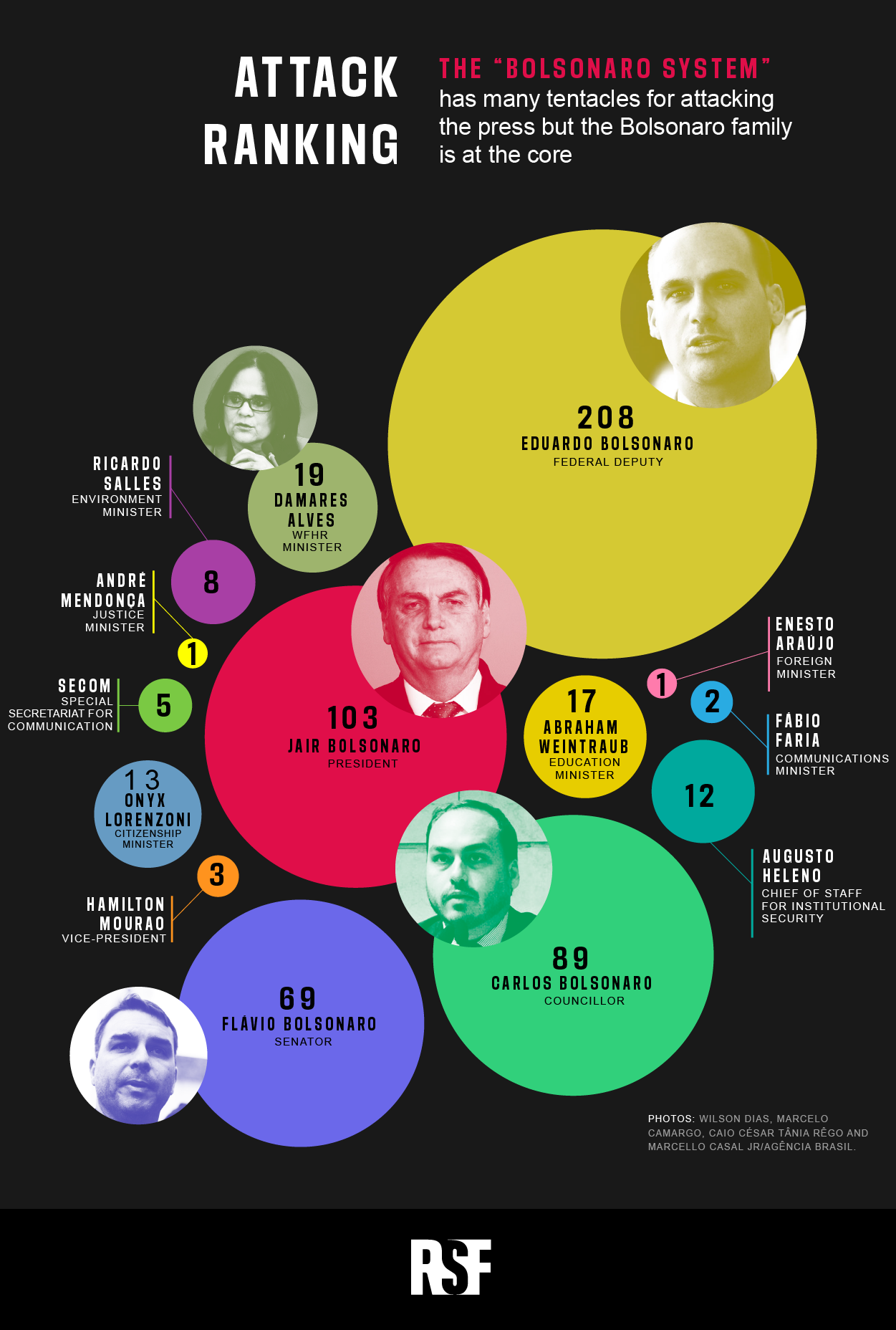

President Bolsonaro and his sons maintained the pace of their attacks on the media, with no fewer than 118 overt* attacks, 66 of them by Eduardo Bolsonaro, who confirmed his position as the family’s leading press freedom predator.

The election campaign saw an increase in arbitrary judicial proceedings against the media, with at least 26 cases of news censorship and demands by candidates for content to be removed from news sites or social media, according to figures compiled by Ctrl+X, a project of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (ABRAJI).

2020 figures

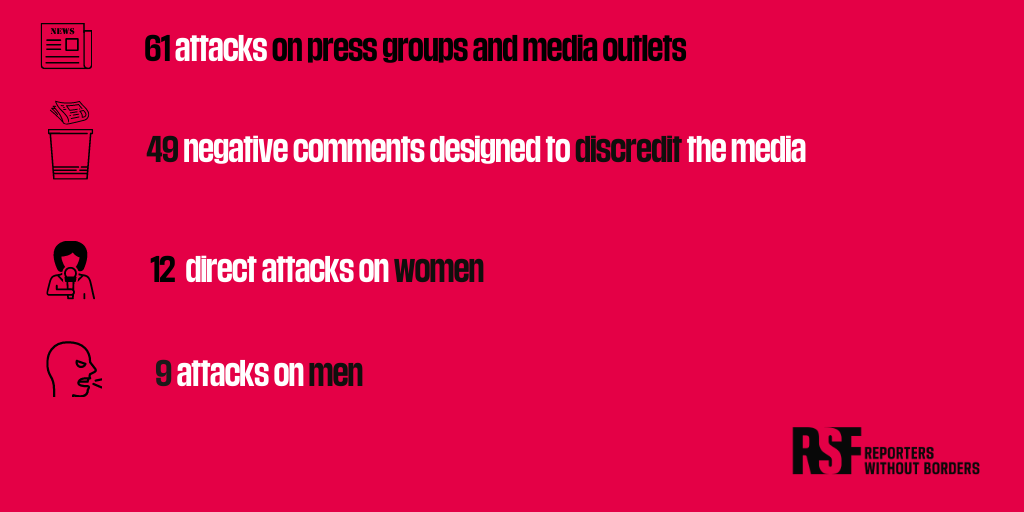

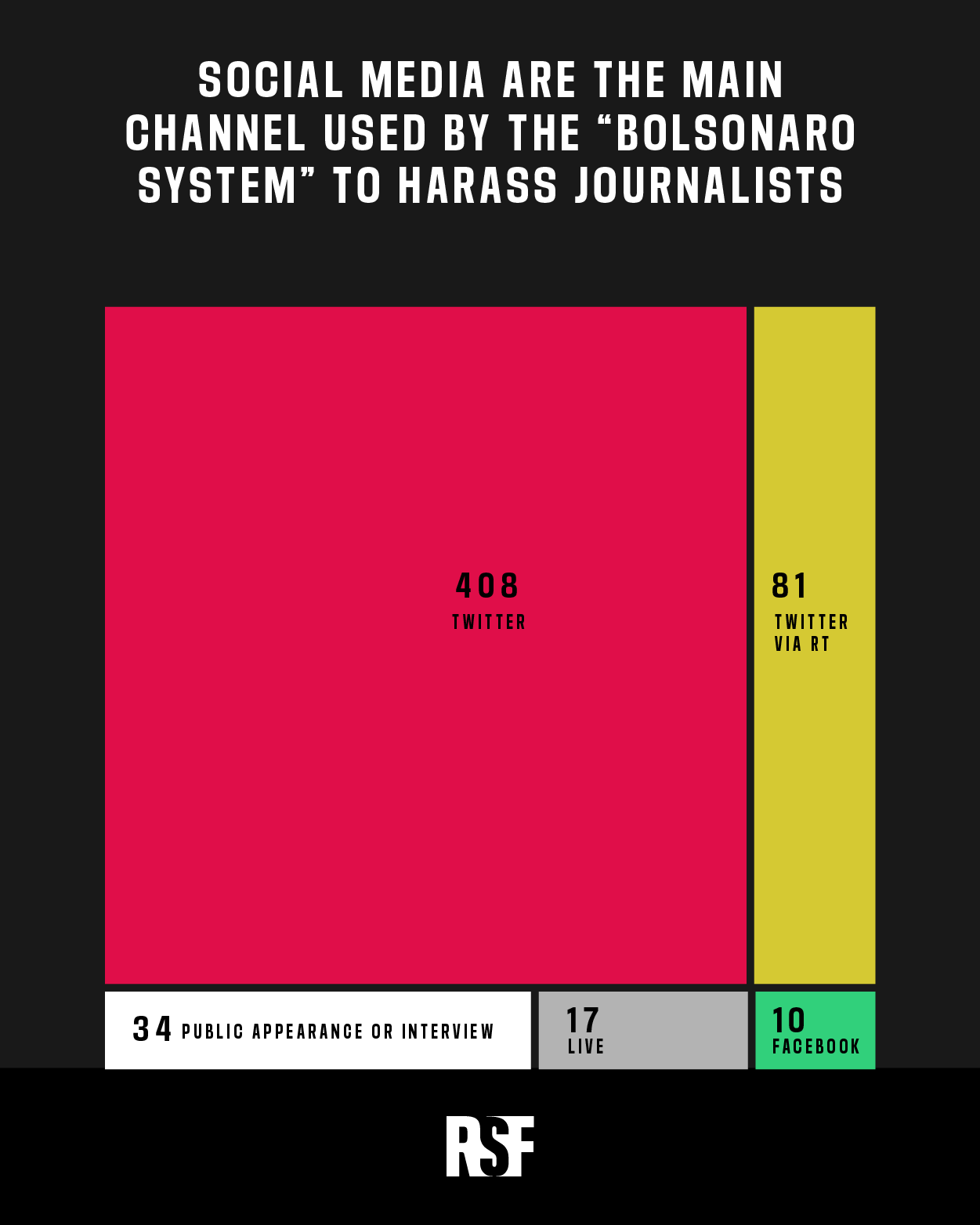

In all, RSF logged no fewer than 581 attacks against the media in the course of 2020. To compile the figures and analyse them in detail, RSF established a partnership with Volt Data Lab, a pioneer in data journalism in Brazil, which produced the following illustrations.

Emblematic cases in 2020

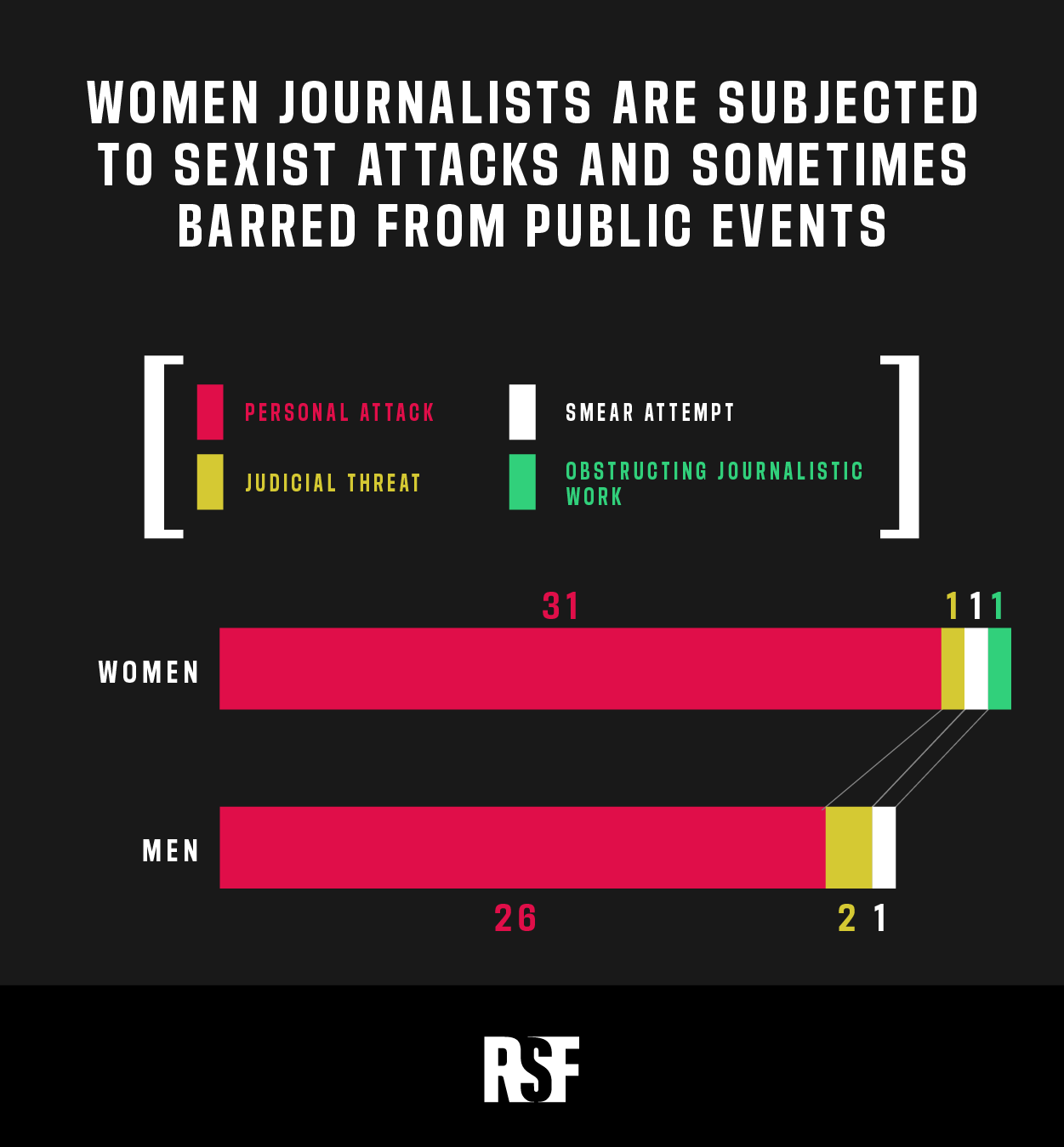

1. Sexist and misogynous attacks – a Bolsonaro system hallmark

Patrícia Campos Mello, a former war correspondent and veteran reporter for the Folha de São Paulo newspaper, reported during the presidential election campaign in October 2018 that businessmen were illegally funding a WhatsApp disinformation campaign designed to get Brazilians to vote for Bolsonaro. Her story triggered a ferocious online campaign of insults and threats against her by Bolsonaro supporters. During an investigation into her claims, an Anti-Fake News Parliamentary Commission heard testimony on 11 February 2020 from Hans Nascimento, the employee of one of the digital marketing companies alleged to have helped send millions of fake WhatsApp messages. Nascimento told the commission that Mello tried to extract information from him in exchange for sexual favours.

Although Mello and Folha de São Paulo issued immediate denials, Nascimento’s claim triggered a torrent of sickening and salacious comments, including by President Bolsonaro himself, and was repeated by several parliamentarians, including the president’s son, Eduardo Bolsonaro. Speaking in the chamber of deputies, he said: “I do not doubt that Ms. Patrícia Campos Mello may have offered sexual favours, as Mr. Hans said, in exchange for information to try to harm President Jair Bolsonaro’s campaign.” Widely relayed on social media, these insinuations triggered a new wave of sexist and misogynous insults and threats against her. The smear campaign had a big impact on Mello, she later told RSF. “When photoshopped memes of me were being spread around, I stopped going out to report on demonstrations,” she said. “This is ridiculous, our country is not at war and it should be normal to cover democratic demonstrations.”

Mello has been one of the Bolsonaro system’s leading targets, but many other women journalists have been subjected to this kind of sexist attacks and have to work in a sickening environment of online smear campaigns by Bolsonaro supporters. Bianca Santana, Vera Magalhães, Constança Resende, Lola Aronovitch and Maria Júlia (Maju) Coutinho are just some of the other women journalists who have been targeted in this way.

2 – Alvorada Palace, setting for repeated public humiliations of journalists

The informal press conferences that President Bolsonaro often holds outside the Alvorada Palace, the official presidential residence in Brasilia, became a symbol of his hostility towards the media in 2020. In a surreal scene broadcast live on the president’s social media accounts on 3 March, Bolsonaro arrived at the press conference in his official car together with a comedian who impersonates him and asked the comedian to distribute bananas to the journalists (which in Brazil symbolizes giving them the finger). He humiliated the same journalists outside the Alvorada Palace three weeks later, on 26 March, amid growing concern about the Covid-19 crisis. “Look, people of Brazil,” he said, pointing at the journalists. “These people say I’m wrong and that you should stay at home.” Turning towards the journalists, he added” “What are you doing here? Aren’t you afraid of the coronavirus? Go home!”

On 26 May, after the latest of many episodes of verbal violence and attacks by Bolsonaro supporters, the Globo group (which includes TV Globo, the O Globo and Valor Econômico newspapers and the G1 news website), the Bandeirantes media group, Folha de São Paulo (Brazil’s leading daily) and the Metropoles news website all decided to temporarily stop attending government press conferences. In so doing, they joined the O Estado de S. Paulo and Correio Braziliense newspapers, which had taken a similar decision shortly before on the grounds that their reporters’ safety was not guaranteed. RSF and its allies meanwhile used the violence as grounds for a court action calling for better security measures for reporters covering the president’s appearances before the media. Although the president’s office later adopted special measures so that reporters would not have to face Bolsonaro supporters outside the Alvorada Palace, it continues to be one of his favourite places for insulting and mocking critical media outlets.

3 – Battle to cover the coronavirus crisis

Annoyed by figures showing Covid-19’s alarming progression in Brazil and, in particular, by a death toll now exceeding 1,000 a day, President Bolsonaro personally issued orders to the health ministry on 5 June for its daily bulletins to be given to the media at 10 p.m. instead of 7 p.m. so that the figures could not be reported during the prime time evening newscasts. “It’s over for the news on the ‘Jornal Nacional’,” he told TV Globo, one of the Bolsonaro family’s favourite targets, which he calls “TV Funeral.”

Interim health minister Eduardo Pazuello referred the next day to over-reporting of Covid-19 cases and ordered several major changes in the way the pandemic figures are counted and announced. In response to these decisions, an alliance of leading media outlets was created on 8 June. UOL, O Estado de S. Paulo, Folha de S. Paulo, O Globo, G1 and Extra said they would henceforth work closely together to get their information directly from the local authorities in Brazil’s 26 states and the Brasilia federal district, and would announce the figures in their own news reports. At the time of writing, this alliance is still functioning and constitutes the most reliable sources of information about the pandemic for Brazilians.

4 – Arbitrary lawsuits against journalists, a national sport

Throughout 2020, Brazilian journalists and media outlets were subjected to a barrage of arbitrary lawsuits encouraged by the Bolsonaro system’s anti-media rhetoric. Most of the lawsuits were brought by government officials or by Bolsonaro allies or supporters.

In one of the most significant cases, a judge in Rio de Janeiro State ordered Luis Nassif, founder and editor of the online newspaper Jornal GGN, and reporter Patricia Faermann to take down no fewer than 11 articles or face a fine of 10,000 reals (1,500 euros). The articles dealt with allegedly improper activities by the BTG Pactual bank (whose founders include economy minister Paulo Guedes), in particular, its acquisition of shares in the state-owned Banco do Brasil bank. The judge ruled in favour of BTG Pactual on the grounds that the articles contained confidential information. All 11 articles are still censored, despite Nassif’s appeal. In a column posted on Christmas Eve, Nassif detailed all of the lawsuits he has had to deal with in recent years and said he was “legally marked to die” for doing his job as a journalist.

Other journalists, such as Hélio Schwartsman, Ruy Castro, Ricardo Noblat and cartoonist Aroeira, and media outlets such as TV Globo, Folha de São Paulo, Ponte Jornalismo, The Intercept Brasil and UOL have also been sued or threatened with lawsuits in 2020 for broadcasting, printing or posting ironic or critical comments or reports about politicians or the government.

5 – Politicization of independent state entities

A report by Brazil’s Court of Auditors (TCU) criticized the lack of transparency and absence of technical criteria in the way the president’s Special Secretariat for Social Communication (Secom) was allocating state advertising. In particular, it highlighted the preferential treatment given to TV channels that toed the government line, especially those run by the SBT and Record media groups. In June, responsibility for allocating state advertising was transferred to the new communications ministry but the person appointed as minister was Fábio Faria, the son-in-law of Silvio Santos, who is the SBT group’s owner and a close friend of Bolsonaro.

Secom has repeatedly attacked media outlets critical of the government, referring to them as the “rotten press” and accusing them – without any grounds – of publishing “fake news.” In September, Secom began putting out false information about the fires that had been devasting the Amazon all year, information that was widely repeated by several ministries and disseminated on social media.

The Bolsonaro system will undoubtedly continue to attack and smear the media until the end of Bolsonaro’s presidential term. Brazil’s journalist will need a lot of resilience and courage to continue working and to reinvent themselves in order to recover the public’s trust. For the country’s sake, they must rise to the enormous challenge.

Brazil is ranked 107th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2020 World Press Freedom Index.

Please refer to RSF’s statement for additional graphs and visual representations of the attacks.