Since Russia's Supreme Court designated the so-called "LGBTQ+ movement" as an extremist organisation in 2023, raids on gay clubs have become increasingly brutal and frequent.

This article was originally published by ‘Russia Post’ on December 6, 2024. An edited version was republished by Global Voices with permission. Historian Rustam Alexander discusses the rising homophobia in Russia, which has translated into increasingly frequent and brutal raids on Russian gay clubs, with clubgoers and employees sometimes charged with criminal offenses.

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian police have raided 59 events as part of their attack against the so-called “LGBTQ+ movement”

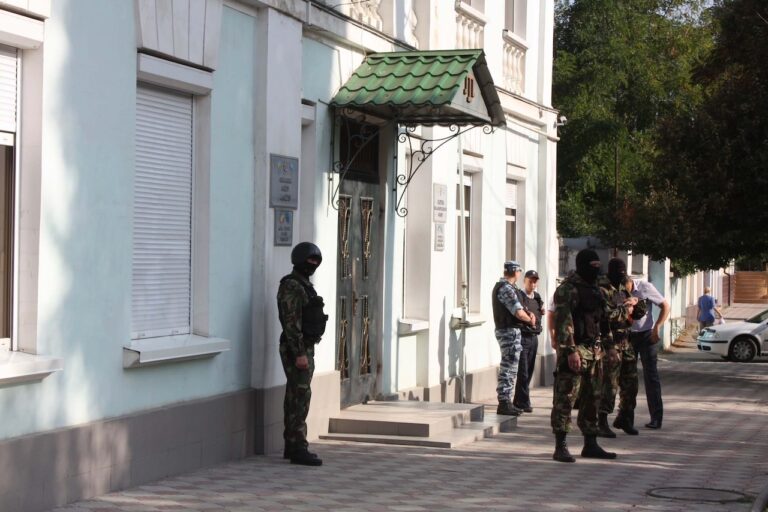

On November 30, Moscow police raided several Moscow gay clubs. Just a week before, on November 23, police raided the club Zebra, in the city of Voronezh, where a private LGBTQ+ party was taking place. Party attendees were wrestled to the ground by uniformed men in masks before being taken to a local police station, where they were given what authorities subsequently described as “preventive talks.” Among the detained was a famous drag performer, Zaza Napoli (born Vladim Kazantsev). The event’s organizers now face criminal punishment of up to 10 years in prison on charges of “LGBTQ+ extremism.”

The Kremlin offensive against a non-existent movement

These are not the first such raids. Weeks earlier, in late October, Russian police raided a night drag show in the Dark House bar in Yaroslavl. The performers were similarly taken to the police station and interrogated for possible involvement in extremist organizations and use of drugs. They were subsequently charged with spreading “LGBTQ+ propaganda,” a much less severe offense than “LGBTQ+ extremism.” In fact, Novaya Gazeta Evropa has revealed that, after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian police have raided as many as 59 events as part of their attack against the so-called “LGBTQ+ movement.”

Such raids on Russia’s gay clubs have become increasingly brutal and much more frequent since Russia’s Supreme Court designated the non-existent LGBTQ+ movement as an extremist organization on November 30, 2023. Less than 48 hours after the decision was made, on December 2, 2023, Moscow police raided three Moscow gay clubs, harassing customers and taking photos of their passports.

Several months later, in March 2024, police raided another gay club, Pose, in Orenburg, a city 900 miles southeast of Moscow. This time the police not only harassed customers but also detained the club’s manager and art director. They were the first individuals in Russia to face LGBTQ+ extremism criminal charges for managing a gay bar.

Early post-Soviet softening

The first “official” gay clubs in Russia began to emerge in 1993, shortly after Boris Yeltsin repealed the laws criminalizing consensual sodomy. While this was a huge victory for Russia’s gay community, Yeltsin’s decision was met with resistance from Russian police. Dismayed at the repeal of the sodomy laws and the growing visibility of gay culture in Russia’s cities, top law enforcement officials vented their frustration in the press.

One of them, Vladimir Pron, an officer serving in a Moscow criminal investigation department, commented in April 1993: “Society longed for debauchery and now it got what it wanted. At the moment, the police have no right to control homosexuals in any way. Even if we know about a ‘gay den,’ we still have no right to make any complaints against them, since these places have often become legalized as clubs.”

Russian police occasionally raided gay clubs, nevertheless, under the pretext of expired liquor licenses and allegations that their customers used drugs. Generally, after detention the customers would be released the same night, while club owners would receive a fine if their liquor licenses had indeed expired. Criminal charges were very rare in these raids, unlike in today’s Russia, where a criminal sentence for managing or going to a gay club has become a very real possibility.

Despite the continuing raids on gay clubs — sometimes more frequent, sometimes less — there has been no Stonewall moment for Russian queer people. Though the sodomy law was repealed in 1993, homophobic attitudes among many Russians continued to prevail. (Surveys conducted by Levada Center indicate that they have been on the rise in recent years: 62 percent of Russians said they disagreed, somewhat or completely, that gays and lesbians should have the same rights as other citizens, versus 35 percent in 2005 and 40 percent in 2010.) Still, LGBTQ+ individuals in Russia were still able to have relatively satisfactory lives — free from persecution, medicalization and ostracism. In this context, gay clubs offered safety and a sense of community.

The increasingly repressive environment

Shortly after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Tinder, a popular dating app for both heterosexual and LGBTQ+ people, left Russia. While Grindr and other similar “hook-up apps” remained, they were less safe than Tinder, which generally regarded as a dating app. Even before the war, Russian antigay vigilante groups used Grindr and other such apps to target, attack and even kill users, with Russian authorities offering no protection to the victims. Given the rapidly worsening situation for LGBTQ+ people in Russia, it is likely that this trend will only intensify. In this context, the sense of community provided by gay clubs became even more significant.

Likewise, gay clubs were often the only spaces where pop culture stars could openly show their support for LGBTQ+ rights. While state-sponsored television in Russia has been dominated by rhetoric about “traditional values” and hostility toward LGBTQ+ people, with many celebrities either criticizing or staying silent, performers like Lolita and Olga Buzova did not shy away from giving concerts in Moscow’s gay clubs.

Оn December 2, 2023, when Moscow police raided the gay club Mono, Buzova was scheduled to perform there. Upon learning of the raid, she cancelled her appearance at the last minute. Today, celebrities are likely to think twice before performing at such venues, especially in light of the backlash surrounding Nastya Ivleeva’s controversial party in late 2023 (see Russia.Post’s coverage of it here).

These days, the only celebrities likely to grace gay clubs with their presence are figures like Zaza Napoli, who, unlike Buzova, is famous primarily among gay club audiences. Yet following his above mentioned detention at Zebra, Zaza Napoli is likely to be cautious too.

In today’s increasingly repressive environment, gay club owners have tried various strategies to survive. Some have even chosen to demonstrate their loyalty to Putin and his military aggression against Ukraine.

In April 2022, shortly after the invasion, Mono gay club banned the songs of Ukrainian artists, including Svetlana Loboda, Max Barskih, Okean Elzy, Ivan Dorn, Nadia Dorofeeva and several others.

Russian artists who had openly criticized Putin’s “special military operation,” such as Oxxxymiron, Valery Meladze and Noize MC (all very popular heterosexual singers), were also blacklisted by Mono. Their songs were prohibited from being played on the club’s dance floor and removed from karaoke playlists. Still, this show of loyalty failed to shield Mono from becoming the first target of gay raids by police in December 2023.

Zaza Napoli has also tried to distance herself from the LGBTQ+ community on several occasions. At one point, the drag performer even exclaimed: “Why should I respect LGBT [people]? They should learn how to behave.” Such lame statements failed to protect her from the police raid at Zebra, however.

There are still numerous gay clubs operating across Russia, and the police will not be able to shut them all down at once. Yet that is only a matter of time — Russian police have a well-established history of targeting these spaces, and there’s no reason to believe they will stop now.

In early December, Valery Fadeyev, who chairs the Putin’s council on human rights, was asked whether the antigay legislation adopted in recent years might negatively affect the lives of LGBTQ+ people in Russia. His answer: “No, it has not [affected them]. I hope everything is still fine with the gays.”