As Turkey increasingly silences free expression during its state of emergency, pressure intensifies for Kurdish writers and artists.

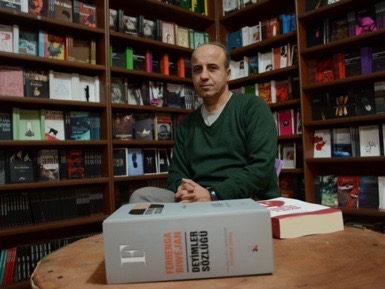

Zeraq, a prominent writer, translator and researcher – best known for his extensive dictionary of Kurdish idioms – was also working as a math teacher at a Diyarbakır public high school. In October, he was expelled from the Ministry of Education and banned from ever working as a public servant again.

The reason, Zeraq says, was his membership at Eğitim-SEN, a left wing teachers’ union, and his participation in a one-day strike organized by various labor unions in December 2015, protesting the state’s violence and military curfews in Kurdish cities.

The legal justification for his removal was one of the many state of emergency decrees passed since 20 July 2016 as a response to the coup attempt. Published in the government’s official gazette on October 29, “Decree No. 675” had a bunch of lengthy lists attached. Zeraq appeared in one of these lists – as ‘Dilaver Döğer’, since the Kurdish letters in his real name aren’t recognized by the state – along with 2,219 teachers who were dismissed from public duty. Buried in another list was the decision to ban Özgür Gündem, the oldest and largest Kurdish daily newspaper published in Turkish.

Together the decrees passed since the state of emergency expelled more than 30 thousand teachers and academics, accusing them of being involved with terrorism. Tens of thousands of public workers have been purged from the judiciary, military and security forces as well.

In the decrees published in the government’s official gazette, the decision to expel thousands of public workers is explained with one vague sentence: “Those who are related, belonging to or in contact with terror organizations, and structures that are considered by the National Security Council as acting against national security, will be discharged from public duty without further operation.” The decree also orders that the dismissed public servants’ passports be immediately cancelled.

Silenced by a state of emergency

With the state of emergency, basic rights and freedoms have come under increasing attack by the ruling AK Party. Powers granted by the ongoing state of emergency are liberally used to silence critics who have a wide range of political views – but no relationship with the coup attempt. Pressures have especially intensified for Kurdish artists – as well as any others who produce works relating to the conflict and openly express support for the Kurdish movement in one way or another.

Kurdish daily Özgür Gündem was shut down on August 16, on the same day the paper’s cartoonist Doğan Güzel was assaulted by the police and detained. Writer Aslı Erdoğan and writer/linguist Necmiye Alpay, members of Özgür Gündem‘s advisory board, were charged with Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) membership and arrested in August. They are still behind bars and face aggravated life sentences.

Tîroj, an arts and culture magazine published in Kurdish and Turkish, and 25 year-old Evrensel Culture magazine were among those media outlets shut down with the October 29 decree. In total, 177 news outlets have been shut with state of emergency decrees, including television and radio stations that broadcast in Kurdish. Close to 150 journalists are in prison (over 110 of them imprisoned during the state of emergency) according to data compiled by Platform for Independent Journalism (P24).

In September, curator Beral Madra withdrew from the Çanakkale Biennial after she was targeted – for supporting the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) – by an AK Party Parliament Member from Çanakkale. Following Madra’s resignation, the biennial was cancelled by the organizers.

41 municipalities belonging to the pro-Kurdish DBP, the sister party of HDP, were seized and mayors were replaced with trustees appointed by the government. Workers in Diyarbakır, Batman and Hakkari’s municipality theatres were reassigned to other departments or fired, and theatres were left dysfunctional. Amed (Diyarbakır) Theatre Festival had to be held in other cities, and Mardin Children and Youth Theatre Festival had to be cancelled altogether because the organizing NGO was shut down, along with hundreds of others, due to state of emergency decrees. Many well-known Kurdish NGOs who work in the arts, such the Kurdish Writers Association and Mesopotamia Cultural Center’s (MKM) various branches in cities such as Diyarbakır, İstanbul and İzmir were also closed down.

In January 2016, 1128 academics signed a petition, “We Won’t Be a Party to This Crime”, urging the Turkish state to end the “deliberate massacre” of Kurds and demanding that peace talks are restarted. The petition angered President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who accused the group of “treason”. Sanctions against the academics have intensified since the state of emergency. As of November, 142 academics have been dismissed (83 of them with state of emergency decrees), 77 suspended and 484 placed under investigation at their schools, according to the group’s website. Four academics were imprisoned (Esra Mungan, Muzaffer Kaya and Kıvanç Ersoy for 40 days and Meral Camcı for 22 days) and released in April.

Artists as teachers under the state of emergency

Prominent writers and artists are among the teachers who were suspended from duty –- some expelled or detained – during the State of Emergency. Most of them live in Diyarbakır and almost all are members of Eğitim-SEN, a leftist teachers’ union critical of the government.

Writer Murat Özyaşar, who has won two of the most prestigious literary awards in Turkey, also works as a high school literature teacher. He had recently been assigned from Diyarbakır, where he worked for more than 10 years, to Istanbul. Özyaşar was suspended on September 8, along with thousands of other teachers from Diyarbakır. His home in Istanbul was raided by armed anti-terror units on October 1, in the early hours of the morning.

That same morning, writer, poet and publisher Rênas Jiyan’s home in Diyarbakır was also raided and he was taken into custody along with other teachers, despite the fact that he was no longer employed as a teacher. Jiyan was a member of Eğitim-SEN as well.

Both were held in custody, without access to their lawyers for five days –- another restriction imposed by the state of emergency. Özyaşar’s case is ongoing at the Diyarbakır courts along with other teachers who are accused of having ties to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), considered a terrorist organisation by Turkey.

As part of the crackdown against teachers who are Eğitim-SEN members, contemporary artists Cengiz Tekin, Erkan Özgen and Şener Özmen, writer/poet İlhami Sidar, writer Kemal Varol and poet Lal Laleş were also suspended in September. Özyaşar, Özmen and Varol were reinstated to their positions on November 25; Tekin, Özgen, Sidar and Laleş on December 2. All of their investigations, however, are ongoing.

“Teachers belong in the classroom”

The government is not hiding that the investigations target Kurdish cities, or that teachers who have attended strikes and protests are being punished.

Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım, during a speech in Diyarbakır in September, said Fethullah Gülen’s followers have been purged from all institutions since the coup attempt, and added that it was now time to do the same for the “separatist terror organization”, implying the PKK. He said they estimated that 14 thousand teachers who worked in the region were “somehow integrated with terror” and would be suspended as a precaution. Deputy Minister of Education Orhan Erdem said “When the trenches were dug, teachers obeyed the unions and joined the strike. The laws don’t allow for the government to be protested just because it has intervened against a terrorist group”, and claimed all teachers were suspended because of “ties to PKK”. The Minister of Education, İsmet Yılmaz, in a speech at the parliament in November, said he didn’t think that protesting against the “righteous battle with terror” was a democratic right. “The teachers belong in their classrooms” he said.

Diyarbakır, Mardin and Batman were the cities – all of them predominantly Kurdish – with the largest number of teachers suspended by the Ministry of Education. On September 8, the decision was announced with a brusque tweet from the Ministry of Education: “11,285 personnel with ties to the separatist terrorist group were suspended.”

Bölücü terör örgütü bağlantılı 11 bin 285 personel açığa alındı.

— MEB (@tcmeb) September 8, 2016

Eğitim-SEN, which has close to 10 thousand members affected by this decision, filed a lawsuit. In their petition, the union stated that most of the suspended teachers were their members and that almost all of these members had participated in the December 2015 strike. Furthermore, the union said that only teachers from eastern and southeastern cities were suspended, while those who participated in the strike from western cities didn’t face any charges.

“Nobody dared to call for support”

Contemporary artist Erkan Özgen has been living, making art and working as a school teacher in Diyarbakır for 15 years. Best known for the compelling videos he’s been producing since the late 1990s, Özgen has previously worked in cities such as Kobane, Beirut, and Damascus, participated in exhibitions in more than 20 countries and was a recipient of the “Prix Meuly” from Kunstmuseum Thun in Switzerland in 2005.

In September, Özgen was suspended while teaching a class on technology and design in a Diyarbakır middle school. He was reinstated to his job last week – after 86 days of suspension – but his investigation by the Ministry of Education is still ongoing.

Özgen attended a residency in Helsinki this past summer, which was meant to “act as a breather” for the artist, according to the organizers. Özgen explains that he did indeed return to Diyarbakır with his morale boosted. “I had projects in mind, I was impatient to start editing my video,” he says.

However, shortly after his return, Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım came to Diyarbakır, in Özgen’s terms “to deliver good news to the Kurdish lands”, and announced that 14 thousand teachers from the region would be suspended. A couple of days later, Özgen learned from the school principal that he was among those suspended.

“Despite everything that’s happening, I want to keep on making art. But it’s really difficult and I haven’t been able to work on anything. Not only because I was suspended, but because the roads of the city I live in are all blocked in the name of security, because there are checkpoints and concrete police stations everywhere…”

He was hurt that none of his colleagues at the school called to offer their support: “Nobody dared to call, the fear sought to be induced to the whole country has seeped into their bones as well.” Though he enjoys working with children, Özgen expressed disenchantment with working as a teacher because of the education system’s problems. “I wish I could only focus on art,” he said.

“Losing the inspiration to write”

Novelist and poet İlhami Sidar, who writes in Kurdish and Turkish, was also among the teachers who were suspended in Diyarbakır for almost three months. Though he’s back in his classroom, his investigation by the Ministry of Education hasn’t been concluded.

As one of the earliest members of Eğitim-SEN union in Diyarbakır, Sidar says he personally knows many of the teachers who were suspended: “Students who received the highest test scores in the country passed through their classrooms, they are without exaggeration the best teachers in Turkey.”

In this climate of repression, Sidar says he has difficulty finding the inspiration to write:

“We have seen the ’90s, with unsolved killings and Hizbullah assassinations, years when hearts had turned into funeral homes. My novels “Angels Also Die” (“Melekler de Ölür”) and “Loyalty” (“Sadakat”) were born from this darkness – holding onto literature was the only way out for me and those like me. We never lost the inspiration to write in this city, where death followed us like a shadow. What’s painful nowadays is feeling that we’re actually starting to lose that inspiration.”

An internationally known artist, who also works as a teacher and was suspended for almost three months, explains that he participated in the one-day strike in December 2015, following the union’s initiative, “so that people wouldn’t die and cities wouldn’t be knocked down.”

Speaking on the condition of anonymity due to the ongoing investigation, he describes similar feelings of dismay: “Every night, I delete everything I’ve written from my phone, I go over my tweets and clean my browsing history. I’m scared to think of what will happen to this land that I chose not to abandon when I had the chance to…”

In Turkey, the ‘Kurdish writer’ has no name. I write as ‘Dilawer Zeraq’ but am expelled from my teaching position as ‘Dilaver Döğer’. That’s the whole issue and dilemma.

Writer Aslı ErdoğanMuhsin Akgün

Contemporary artist Erkan Özgen Max Geuter

“Despite everything that’s happening, I want to keep on making art. But it’s really difficult and I haven’t been able to work on anything. Not only because I was suspended, but because the roads of the city I live in are all blocked in the name of security, because there are checkpoints and concrete police stations everywhere…’’

Erkan Özgen, still from Adult Games, 2004Photo courtesy of the artist

Novelist and poet İlhami Sidarİlhami Sidar

“Every night, I delete everything I’ve written from my phone, I go over my tweets and clean my browsing history. I’m scared to think of what will happen to this land that I chose not to abandon when I had the chance to…”

Elif Ince is a freelance journalist and researcher based in Istanbul, Turkey. Siyah Bant is a platform to research and document cases of censorship in the arts in Turkey and to defend artistic freedom of expression.