An investigation has revealed a list of 130 individuals subjected to profiling by the Colombian military, including 30 journalists - among them correspondents for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, NPR, and a National Geographic photographer, all US citizens. IFEX Regional Editor Paula Martins looks at the recent events - and the broader ramifications.

Spying in 2019 – profiling and secret dossiers

In late December 2019, Colombian President Ivan Duque announced the retirement, for personal reasons, of general Nicacio Martinez as commander of the national army. In mid January 2020, the local magazine Semana published a piece reporting that, behind the retirement, there was a huge scandal involving the use of US funds to create a surveillance scheme put in place by the Colombian Army to spy on journalists, politicians, judges and even officers from other units of the armed forces during 2019.

According to a foreign intelligence worker living in Colombia, US officers started to receive news that sophisticated equipment donated to support the fight against drug trafficking and guerrillas was being put to illegal use, and that some funds provided to the Colombian army were being diverted to the pockets of certain officers. A military source told Semana that his unit would create false reports, based on non-existent sources, to obtain resources that would then be divided between the heads of the operations. In other cases, according to another military intelligence source, the victims were political targets of all ideological shades, but of no interest to national security concerns.

At first, no names were provided; just mobile numbers, email accounts, and an order to investigate. Once they started the investigation, officers realized who they were surveilling. Dossiers, organized under the label “Special Services”, would contain extensive information on targets, including excerpts of their conversations on social media and messaging apps, photographs, videos, network of contacts, and maps tracing their movements.

Also according to Semana, in 2019 the Military Intelligence Support Command (“Caimi”, for the acronym in Spanish), acquired the platform known as Invisible Man, which allows for the installation of malware in hacked equipment, from a Spanish manufacturer. El Espectador reported on the use of Voyager by the Army, a tool produced by an Israeli company. Tactical mobile equipment, such as StingRay, was also allegedly employed. Most of the information, however, was collected through Open Source Intelligence – Osint, due to the low cost involved.

Threats to silence investigative journalism

As a result of Semana’s 2019 investigation, the magazine was constantly watched and its directors and staff were followed and threatened. “Condolence notes” were sent to the newsroom and to journalists’ families, and a tombstone was placed in the car of one of the journalists.

After the case was brought to law enforcement authorities, those investigating it also began to be threatened. One received a note telling him to look away from the Army Command and to only make public what the media already knew. The note ended: “Enjoy your lives, those twins, your family. Your wife is a very good accounting student, enjoy your Renault Simbol [sic] car, your daughter and your ex-cop wife”.

Historical roots and recurrent scandals

Semana’s reporting comes 10 years after another critical case involving illegal tapping of communications in Colombia by the Security Administrative Department (DAS, for the acronym in Spanish) in 2009. Media accounts report that the national spy agency surveilled and harassed more than 600 politicians and public figures.

As a result of those reports, DAS was shut down and 70 people were investigated by law enforcement agencies; 22 pled guilty or were convicted, including the General Secretary of the Presidency and the former director of DAS. The case also led to the creation of some control mechanisms and the passing of a dedicated legislation in 2013: the Law on Intelligence and Counterintelligence (Statutory Law 1621).

There was an expectation that, since then, things had changed in Colombia. It is now clear that was not the case.

Experts now question the impact of the Intelligence Law, mainly due to its poor implementation, but also due to serious gaps in its provisions. The bodies put in place to exert a degree of civil control over the military, such as the relevant Senate commission and the system for the purging of classified intelligence files, are either not operational or ineffective.

Commentators argue that impunity has contributed to the current situation, pointing to the lack of action and accountability after the disclosure of the Andromeda Operation in 2014, when a hacker admitted to purchasing intelligence from an illegal wiretapping operation run by the Colombian military. The surveillance operation, installed in a restaurant, targeted negotiators involved in the peace talks then underway.

In 2015, Privacy International released an investigation based on confidential documents and testimonies, showing that the 2013 reforms had been “undermined by surreptitious deployment of mass, automated communications surveillance systems by several government agencies outside the realm of what is proscribed by Colombia’s flawed intelligence laws”. The organisation concluded that Colombia had built a “shadow state” of mass surveillance.

Today: Little accountability and no structural change

According to El Pais, investigations into the 2019 reports of illegal surveillance are running “at a turtle’s pace”, and the government began treating the case as solved after the removal of General Martinez.

In early May, Semana published a new piece, this time referring to a list of 130 individuals who had been subject to profiling, 30 of whom were journalists. The list included correspondents for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, NPR, a National Geographic photographer and the head for the Americas of NGO Human Rights Watch, all US citizens.

Hours before the article was published, the government announced that 11 military officers had been temporarily removed pending disciplinary proceedings resulting from reports of illegal surveillance – officers who had supposedly been under investigation since January 2020. No details were given on their names, ranks or roles.

Additionally, these developments have been limited to administrative proceedings within the armed forces. Senator Juan Manuel Galán, one of the authors of the 2013 Law on Intelligence and Counterintelligence, affirmed in an interview published by El Colombiano that the civilian criminal justice system must respond to the case, not the military justice system.

Evidence points to the fact that the Colombian army has been carrying out intelligence operations outside of any civil and political controls, on targets that cannot be considered “legitimate”, obeying no clear chain of command, and for purposes that are, at a minimum, uncertain.

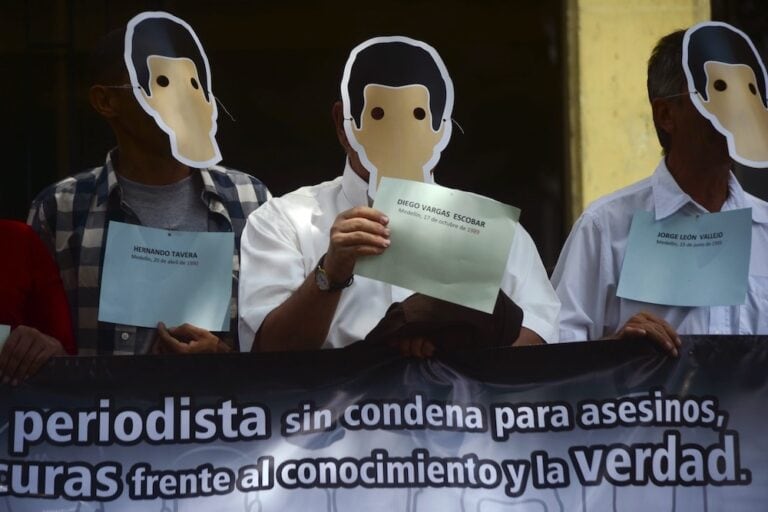

In response to Semana’s reports, a number of the profiled journalists and their supporters released an open letter titled “Why are we under surveillance?” They list many of the unanswered questions concerning the case, including who ordered the operation, who knew about it, what the information collected was intended to be used for, and what actions would be taken to guarantee that journalists can carry out their work without being targeted by profiling, surveillance and stigmatization.

The Commander of the Colombian Military Forces, General Luis Fernando Navarro, told Reuters in early May 2020 that “Illegal spying is not an institutional policy but reflects the individual actions of a few officials who have not just lost their jobs but could face jail time”. President Duque affirmed he “will not allow members of the Public Force to work against the law”.

However, on 22 May a New York Times piece questioned the military and government claims that the scandals related to the acts of some “rotten apples” within the institution, and called for a full reform of Colombian military intelligence.

The research carried out by Privacy International supports the need for this. Surveillance is deeply entrenched in the army, and the problem extends far beyond the acts of individual officers. Communications surveillance has historical roots in Colombia and has been integral to the internal conflict. According to their report, “[t]he key agencies in Colombia that monitor communications all compete for resources and capabilities. This has resulted in overlapping, unchecked systems of surveillance that are vulnerable to abuse”.

Deep and lasting impacts on freedom of expression

Pedro Vaca, director of IFEX’s Colombian member organisation Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa (FLIP), stresses the need for answers. The case continues to be handled with little transparency. While investigations drag on, slowly and obscurely, there remains a real risk to all those on the list.

La Liga Contra el Silencio and its editor, Gina Morelos, appear on the list. Morelos asks how journalists going about their regular work can be seen as a threat to national security. When I ask her about the investigation, she answers: “¿Cuál investigación? En nuestro país, el silencio ruidoso es una constante.” [What investigation? In our country, a noisy silence is the constant.”]

John Otis, NPR and Wall Street Journal journalist and correspondent for IFEX member the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in Colombia, was another of the targets. He told IFEX he believes that the journalists on the list were probably targeted because of pieces critical of the military – that it seems there is a sentiment within the army that all those who do not fully support their work are against them. He also speculates that some journalists are being surveilled because they are working on stories where their sources are members of drug trafficking and guerrilla groups.

The impact on press freedom is clear: journalists are being seen as threats and targeted for exercising their legitimate work, and the protection of their sources – essential for accessing information to help Colombians to better understand their complex and difficult socio-political context – is under jeopardy.

As highlighted by FLIP, the profiling of journalists by the Colombian army goes beyond the legal limits and objectives of the intelligence functions constitutionally allowed to the state.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and its Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression have stated that the surveillance of persons must be legal, in a formal and material sense, necessary, and proportionate. The objectives according to which the monitoring or interception of communications is enabled must be expressly stated in the law, and in all cases the laws must establish the need for a prior judicial order. Mass surveillance of communications may in no case be considered proportional.

“Along the same lines, the systematic collection of public data – voluntarily exposed by the owner of such data, such as blog posts, social networks, or any other intervention in the public domain – also constitutes an interference in people’s private lives. The fact that the person leaves public traces of his activities – inevitably on the internet – does not enable the state to collect it systematically except in specific circumstances where such interference is justified”.

Civil rights under attack; civil society counters

Unconstrained surveillance powers threaten not only the right to privacy, but also a broad spectrum of rights, including freedom of expression, assembly and association, and the prohibition of discrimination.

The problem seems to affect many other countries in the region. In 2019, representatives from various non-governmental organisations from Latin America noted the gradual implementation of surveillance technology in aiding national security efforts.

Lack of studies and transparency during the preparation of technology roll-outs are commonplace. In Argentina, for example, IFEX member ADC (Asociación por los Derechos Civiles) has been championing a specific piece of legislation regulating the use of open-source intelligence (OSINT) and social media intelligence (SOCMINT), asking for an open and participatory legislative process.

The coalition AlSur – in which IFEX members ADC, Derechos Digitales, Fundación Karisma and R3D take part – affirms that this trend is especially worrisome in a regional context marked by long-standing dictatorships, armed conflicts, and systematic and generalized violation of human rights – and it is aggravated by a predominant culture of corruption, impunity, and lack of transparency.

Fabrizio Scorlini, from the Latin American Initiative for Open Data (ILDA), says that “the increasing scale of illegal surveillance in Latin America – enabled by state procurement of surveillance and hacking software – is raising urgent questions about its impact on civil rights”. States should adopt a clear framework considering “issues of necessity and proportionality to acquire and use these technologies, as well as identifying which agencies will be allowed to operate them”.

These parameters could indeed guide badly-needed reforms to Colombia’s legal and policy framework, as well as those of neighboring countries. Thorough, transparent and conclusive investigations are also needed. However, enforcement of legal guidelines, implementation of civil controls, and public monitoring of intelligence agencies require true political commitment. Today, Colombia faces this challenge, along with the opportunity to make a pledge to democracy, the rule of law, and human rights.