Venezuela has granted powers to the military to use force to control peaceful demonstrations, Human Rights Watch said today. On January 23, 2015, the Defense Ministry issued a resolution authorizing the Armed Forces to maintain “public order” and “social peace” during “public meetings and demonstrations.”

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 12 February 2015.

Venezuela has granted powers to the military to use force to control peaceful demonstrations, Human Rights Watch said today. On January 23, 2015, the Defense Ministry issued a resolution authorizing the Armed Forces to maintain “public order” and “social peace” during “public meetings and demonstrations.”

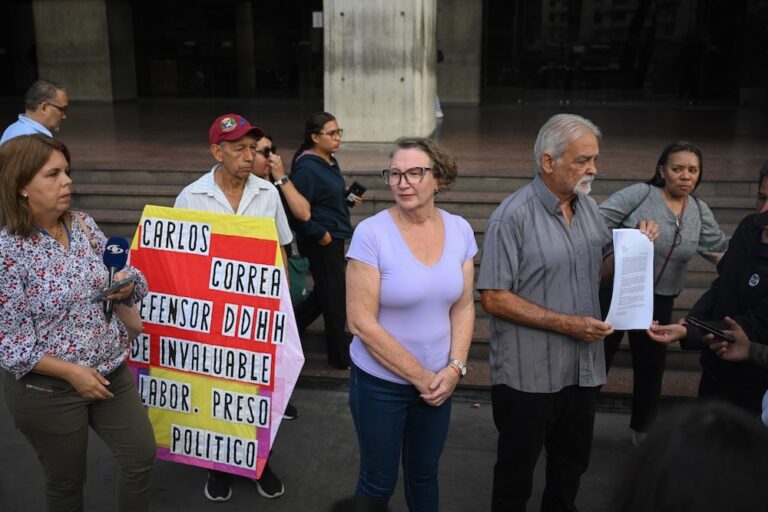

Meanwhile, a year after a violent crackdown on nonviolent demonstrators and bystanders, there has been little accountability for the scores of abuses – including killings, arbitrary arrests, beatings, and torture – committed by security forces. The opposition leader Leopoldo López and more than two dozen others arrested in the context of the protests that began on February 12, 2014, and continued at least through April, remain in detention.

“Deploying the military to control political protests is a very bad idea, especially in a country where security forces already have a record of getting away with egregious abuses against nonviolent demonstrators,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas executive director at Human Rights Watch. “Venezuelans have good reasons to fear that involving the military, trained for warfare and not policing, will only make matters worse.”

The administration of President Nicolás Maduro should revoke the new powers granted to the military and immediately and unconditionally free López and others arbitrarily arrested during the 2014 protests, Human Rights Watch said.

While some protesters engaged in violence at some of the 2014 protests, including by throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails at security forces, Human Rights Watch’s research shows that the security forces repeatedly used unlawful force against unarmed people who were not engaged in violence. Some of the worst abuses documented were against people who were not participating in demonstrations, or were already detained and fully under security forces’ control.

Based on the government’s own accounting, there has been little accountability for these violations. As of November, prosecutors had received 242 complaints of alleged human rights violations during the demonstrations, including two cases of torture, though Human Rights Watch documented more. The Attorney General’s Office reported that prosecutors had concluded 125 investigations, bringing charges against 15 members of public security forces.

When addressing the United Nations Committee Against Torture in November, a representative of the Attorney General’s Office said that two police officials had been convicted for “events that occurred” during the protests, but provided no information regarding the nature of their crimes or the convictions.

After the protests began, the government immediately blamed the political opposition for inciting violence, and on February 12 a judge acted on a prosecutor’s request and ordered López arrested. He has been detained arbitrarily in a military prison since he turned himself in on February 18, and remains on trial. In criminal procedures that violated due process guarantees, two opposition mayors were convicted and given prison sentences of 10 and 12 months for failing to clear streets in their municipalities where demonstrators were protesting.

In October, the UN high commissioner for human rights urged Venezuela to release arbitrarily detained protesters and politicians. The UN Committee Against Torture said in November that Venezuela should immediately release López, one of the mayors, and “everyone who has been arbitrarily detained for exercising their right to express themselves and protest peacefully.”

In December, the United States imposed targeted sanctions on Venezuelan military and civilian officials allegedly responsible for human rights violations during the protests. The sanctions include refusing or cancelling visas for certain officials and freezing their personal assets in the US.

The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) rejected the sanctions, contending that they violate the “principle of non-intervention” in Venezuela. Similarly, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) criticized the sanctions and urged the international community to refrain from “intervening, directly or indirectly, in internal affairs” of other states. Neither UNASUR nor CELAC has condemned the security forces’ systematic abuses of protesters, nor the criminal prosecution of Maduro’s political opponents.

In January 2015, the government of Colombia broke this collective silence by calling for releasing López, after Venezuela refused to allow former President Andrés Pastrana of Colombia and former President Sebastián Piñera of Chile to visit López in prison. Maduro accused the two former presidents, and former President Felipe Calderón of Mexico, who also traveled to Caracas, of supporting “a coup against the government” and a “terrorist group of the extreme right,” while the Venezuelan Foreign Affairs Ministry lamented that the Colombian Foreign Affairs Ministry supported “positions that run counter Venezuelan democracy” and constituted a “dangerous setback” in the two countries’ bilateral relations.

“Latin American governments need to speak up individually and collectively about the crackdown on protesters in Venezuela, and to call on the Maduro administration to hold security forces accountable for the abuses and release opponents who have been arbitrarily jailed,” Vivanco said.