Free expression violations have been occurring in Venezuela for many years. So why is the latest crisis an unprecedented event for journalists and media?

The following is a translation of an article published on ifex.org in Spanish, on 6 April 2017.

Complicated. That’s how the landscape in Venezuela seems now that the Supreme Court of Justice (Tribunal Supremo de Justicia, TSJ) assumed all National Assembly powers for a few days, dissolving Parliament by judicial means.

With Judgement No. 156, the TSJ gave itself all of the legislative powers that constitutionally belong to the National Assembly. In order to deliver this ordinance, the TSJ disregarded the parliamentary immunity of members who make up the Assembly. Additionally, it mandated that President Nicolás Maduro govern the country by means of decrees, based on an “exceptional” arrangement.

The dissolution of Parliament generated concern from the Organization of American States (OAS) and civil society organisations, and it was widely condemned by dozens of countries – Maduro was eventually forced to reverse the dissolution and called upon the TSJ to review the ruling, which the court did on 1 April 2017. The president could not, however, reverse the sense of chaos and instability that reigns in the country, according to civil associations and opposition parties.

Despite this backtracking, social problems and repression and violation of human rights persist in Venezuela. These issues have also reached unprecedented levels, according to various organisations – both local and international – that monitor the situation.

Organisations perceive an “absence of democratic institutionality” in the country; something that has been in the making for many years given the attempts made by the Maduro government to silence an increasing number of popular protests in light of the country’s economic and social collapse.

Out of 180 countries, Venezuela is ranked as number 139 on the World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in 2016.

The severe situation in Venezuela was addressed during a mid-year meeting of the Inter American Press Association (IAPA), an organisation that brings together hundreds of media outlets from all over the Americas. In two resolutions approved by the Assembly, this organisation defending freedom of expression condemned the TSJ judgment because it “compromises democratic values.” It also warned that, at this point, freedom of expression in Venezuela has little space given that attacks against journalists, the media, and the exercise of journalism, are worsening.

For IAPA, the precedent set by the TSJ “is clear proof of the unwavering political control that the Executive Branch exercises over the Judicial Branch … which not only violates divisions of power, but also the basic guarantees for citizens in a nation governed by the Rule of Law.”

Venezuelan members of the IAPA also report that the Maduro government has developed all kinds of mechanisms to limit the publication and dissemination of news on the internet. They have gotten to the point of hiring international hackers for these ends, and have used intimidation, harassment and even paper shortages to halt print media.

In fact, an RSF report reveals that, since August of 2016, more than 20 journalists have been prevented from entering, or have been expelled from, Venezuela upon arriving at the airport. Journalists and others have also had their work supplies confiscated.

More attacks on journalists

The government’s legal move only sparked more protests, and with these, came more attacks on journalists. On 31 March, amidst a student demonstration against the TSJ judgments, several journalists were physically assaulted.

During this demonstration, journalist Elyangélica González, correspondent in Caracas for Caracol Radio of Colombia and the U.S. chain Univision News (Noticias Univisión), was brutally beaten by dozens of military personnel while she tried to cover the event.

“They grabbed my phone. I tried to take out the other one, but they took that one away from me too; they broke it, burned it and they arrested me. I’m totally bruised up, have hair in my hands; I’m scraped all over, beaten,” said the journalist when she was able to re-establish contact with the Colombian radio station for which she was covering the events.

This incident was heavily criticised by several Colombian organisations and media outlets as something that was “humiliating,” “inhumane” and “authoritarian,” and an indication of the “systematic disregard for freedom of the press by Venezuelan authorities.”

Chain reactions

The TSJ judgment was also heavily criticised internally, within the country.

According to IPYS Venezuela, an organisation defending freedom of expression, there are no constitutional provisions authorising the TSJ to assume National Assembly functions, which is why they consider the decision to be a “Parliament coup.”

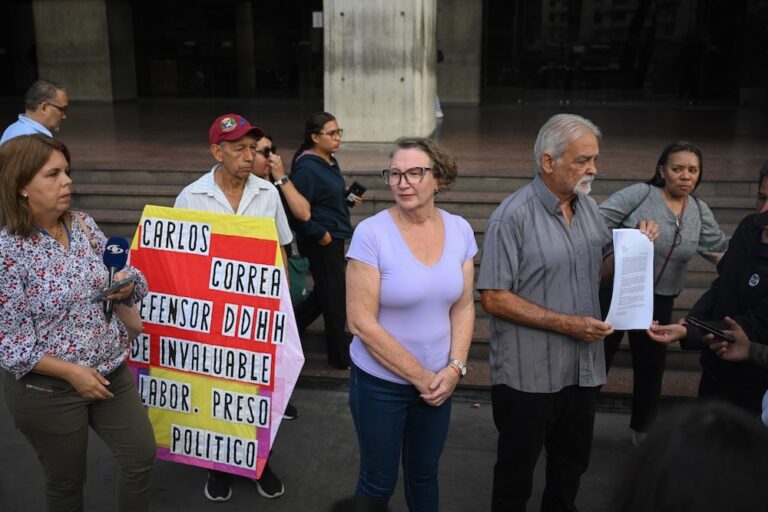

A declaration signed by IPYS Venezuela and 63 Venezuelan civil society organisations denounces this measure as a violation of the right of citizens’ participation in public matters, in addition to infringing upon the Constitution.

And they weren’t the only ones to express their profound concern. Espacio Público, an NGO defending human rights, together with 11 other Venezuelan organisations, condemned the action, which they considered to be “a coup on sovereignty of the people.”