Telefónica's report was a gamechanger for digital rights activists in Venezuela.

This statement was originally published on advox.globalvoices.org on 17 March 2023. It is republished here under Creative Commons license CC-BY 3.0.

Venezuelan digital rights activists have suspected surveillance practices and unjustified monitoring of private communications in Venezuela for years but had little evidence until June 2022. That month, Telefónica, the parent company of Movistar Venezuela, published a transparency report. It revealed data pointing to a mass surveillance program using systematic and unmethodical interceptions of their customers’ private communication by order of Venezuelan government entities.

According to the report, Telefónica intercepted — by order of Maduro’s administration — the communications of more than 1.58 million Movistar subscribers in 2021. That is 20.5 percent of Movistar telephone and internet accounts. They intercepted or “tapped” calls, monitored SMS, shared people’s locations, and monitored their internet traffic. The number of lines affected by interceptions has increased sevenfold since 2016, when there were 234,932 access breaches.

At the time, Telefónica’s report sparked a huge conversation about digital authoritarianism and privacy in Venezuela, but most importantly, it highlighted the extent of Maduro’s government surveillance and persecution of dissident voices. The intimidation, persecution, arbitrary detention, mistreatment, and torture of activists, humanitarian workers, journalists, and citizens have been widely covered in the latest UN Fact Finding Mission Report, published in September 2022. Venezuela’s authoritarian government under Nicolas Maduro dates back to 2013, with the election of Nicolás Maduro after Hugo Chávez died. This had a big impact on the country’s digital media ecosystems.

Telefónica’s report adds that Movistar Venezuela did not receive interception or metadata collection requests through judicial orders, as stipulated by Venezuelan law, but rather from the police, the military, and other entities such as the General Prosecutor’s office (Ministerio Público), the Criminal Scientific Investigations Agency (Cuerpo de Investigaciones Científicas Penales y Criminalísticas or CICPC), and even the National Experimental Security University (Universidad Nacional Experimental de la Seguridad).

Communication metadata is information about communication beyond its content. For example, who a user is calling, the location and duration of the call, routing information, or the client’s personal data. The Telefónica report identified 997,679 lines (13 percent of Teléfonica’s lines) affected by metadata requests.

Governments often argue that the interception of communications can be a legitimate tool to investigate serious crimes. However, digital rights activists argue that these powers must be used in accordance with national and international laws, human rights standards, and due process in order to protect citizens’ rights. The government did not react to Telefónica’s report.

In Venezuela, orders to intercept communications must come from the courts. There are particular exceptions in case of emergencies and flagrant crimes for which the CICPC can directly request communication companies to intervene. Still, in these cases, a prosecutor must be notified, and their approval must be included in the investigation file. Venezuelan laws also stipulate requesting the prosecutor to maintain transparency and legitimacy throughout the process. The legal framework to intervene in private communication is established in the Organic Code of Criminal Procedure, articles 205 and 206. For metadata interceptions, requests must go through Administrative Ruling No. 171 and Article 29 of the law against kidnapping and extortion.

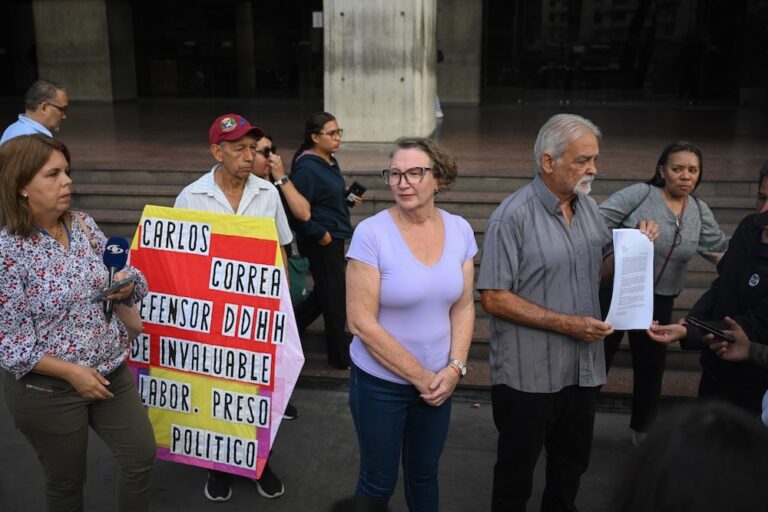

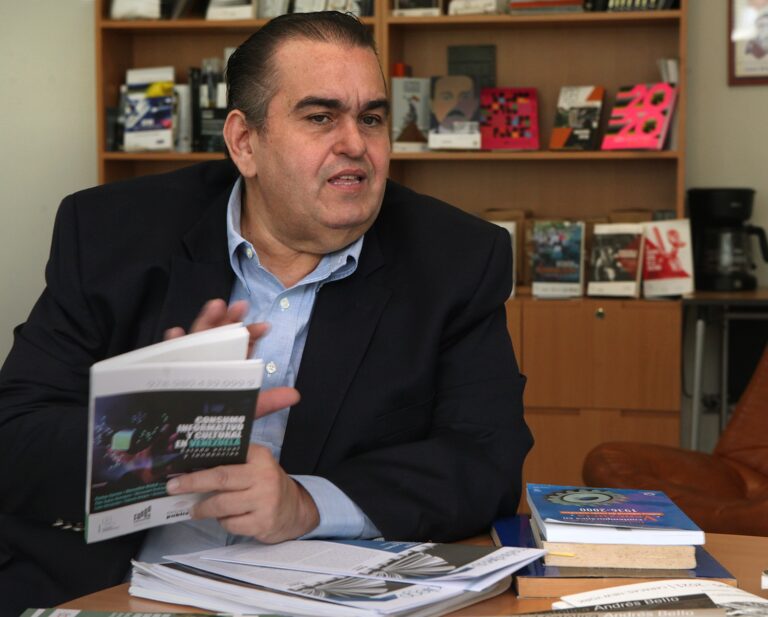

The large number of intercepted lines highlighted in Telefónica’s report indicates more than an unusual amount of emergency cases; for many, it points to the systematic abuse of civil and digital rights. Although this is the first time there is relevant evidence of the scale of the issue, VE sin Filtro, an NGO focused on digital rights and internet restrictions in the country, registered similar interceptions in their 2021 annual digital rights report.

VE sin Filtro’s report draws attention to a specific incident: the WhatsApp account of a Venezuelan NGO, which was used to communicate with victims of state violence, was hacked. “Unlike the cases we usually see, none of the users had been tricked or subjected to a phishing attack. This incident was probably perpetrated by or in coordination with state agents, which is not usually the case with fraudsters or other types of attackers. The incident occurred while Venezuela was being investigated by the International Criminal Court Prosecution Service and the UN Council on Human Rights was working on its fact-finding mission,” the report said.

Telefónica also reported that the Venezuelan authorities filed to block 20.5 percent of websites. For context, Germany requested 0.11 percent, Spain 0.05 percent, and Brazil 0.28 percent. Many other Latin American countries did not file any requests at all.

For rights activists, Telefónica’s data compounds other human rights violations in Venezuela at the hands of Maduro’s government. Marta Valiñas, president of the UN Fact-Finding Mission, says: “Our investigations and analysis show that the Venezuelan state uses the intelligence services and their agents to suppress dissidence in the country. This leads to the commission of serious crimes and human rights violations, including acts of torture and sexual violence. These practices must cease immediately and those responsible must be investigated and prosecuted in accordance with the law.”