In addition to the well-publicized arbitrary arrests and prosecutions of opposition politicians, Venezuelan authorities brought criminal charges against dozens of lesser-known critics over the past year.

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 6 August 2015.

The government of President Nicolás Maduro and its political supporters in parliament are misusing the criminal justice system to punish people for criticizing its policies, Human Rights Watch said today. In addition to the well-publicized arbitrary arrests and prosecutions of opposition politicians, Venezuelan authorities have brought criminal charges or threatened to open criminal investigations against dozens of lesser-known critics over the past year.

On July 24, 2015, National Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN) agents detained Fray Roa Contreras, a Venezuelan businessman, a day after he criticized the government’s economic policies in a CNN television interview. Contreras remains in detention and is being prosecuted for allegedly disseminating false information that “causes panic in the people or maintains them in a state of anxiety,” media reports said.

“The government of Venezuela uses the justice system as a façade, but the reality is that Venezuelan judges and prosecutors have become obedient soldiers,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “Venezuelan authorities have routinely abused their powers to limit free expression, undermining open, democratic debate that is especially critical with legislative elections coming up in December.”

Human Rights Watch documented 31 cases in the capital, Caracas, and four states – Aragua, Carabobo, Lara, and Zulia – in which people are facing or were threatened with criminal charges for public statements critical of the government. These include 22 people linked to Venezuelan media outlets that published reports alleging that Diosdado Cabello, the president of the National Assembly and a member of the governing party, had links to a drug cartel. The intelligence service detained and interrogated 6 others, including 5 who were then prosecuted for their statements. Of the remaining three, authorities opened a criminal investigation against two, and threatened the third with prosecution.

Cases Human Rights Watch documented include a medical doctor who was detained by intelligence agents and threatened with prosecution for criticizing shortages of medicines on TV, an engineer who was detained after he was quoted in a local newspaper criticizing government policies that regulate access to electricity, and a fortune-teller with a diagnosed psychological disorder who was detained and prosecuted for tweeting, among other things, that “the dictatorship in Venezuela” would “die.”

While most of those detained have been conditionally released, the criminal charges or investigations have not been dropped, Human Rights Watch said.

In 2005, President Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, and his supporters in the National Assembly expanded the scope of laws punishing expression deemed to insult public officials and established draconian penalties for defamation. The current criminal code provides for prison sentences of up to five years for anyone who causes “panic” or “anxiety” in the population by disseminating “false information.” It also provides for penalties of up to four years in prison for publishing information that “implicates an individual in a specific event capable of exposing the person to disdain or public hatred, or [that is] offensive to the person’s honor or reputation.”

The lack of an independent judiciary in Venezuela greatly enhances the threat these laws pose to free speech, Human Rights Watch said. The Venezuelan judiciary has largely ceased to function as an independent branch of government since a political takeover of the Supreme Court in 2004 by President Chávez and his supporters.

“This dramatic abuse of the justice system is possible because there are no truly independent institutions left in Venezuela capable of protecting human rights and acting as checks and balances of executive power,” Vivanco said. “Threatening and prosecuting people who speak out about Venezuela’s problems isn’t going to make those problems go away.”

For additional information on cases documented by Human Rights Watch, see below.

Recent Cases Reviewed by Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch identified 31 people who were prosecuted or threatened with prosecution between October 2014 and July 2015, interviewed victims or their lawyers in Venezuela, and reviewed official sources, including judicial files and reports in state-owned and administered media.

Fray Roa Contreras

On July 24, 2015, intelligence agents detained Fray Roa Contreras, the general director of the Venezuelan Federation of Liquor Sellers, a day after he said on CNN that the federation had requested a “dialogue” with President Maduro to address the “crisis” the industry was facing. The federation had previously criticized official policies, including rules that limit imports of raw materials that local producers need to make alcoholic beverages in Venezuela.

On July 28, the media reported that Contreras had been charged with disseminating false information that “causes panic in the people or maintains them in a state of anxiety,” which carries a penalty of up to five years in prison.

A day later, Cabello, the National Assembly president, said on TV, based on information provided by a “patriotic informant,” that Contreras’ statements were part of a “plan to make the Venezuelan people lose its patience” prior to the legislative elections in December. The media reports said Contreras remains detained at the intelligence agency’s headquarters in Caracas.

Luis Vásquez

On April 18, intelligence agents detained Luis Vásquez, an engineer who presides the Electrical Commission at the Engineers Bar Association in Lara State, after he was quoted in a local newspaper criticizing government policies that govern access to electricity. Electricity cutoffs are a recurrent problem in Venezuela.

The next day, agents in four SEBIN vehicles intercepted a vehicle Vásquez was driving on a road in Barquisimeto, Lara State, and, without showing an arrest warrant, detained him and drove him to the intelligence agency’s headquarters, Vásquez told Human Rights Watch. The agents interrogated Vásquez until 3 a.m., without allowing him to have access to a lawyer, asking him about his statements and whether he belonged to an opposition political party, he said.

On April 19, the justice minister said on Twitter that Vásquez was part of a “mission” to “destabilize the tranquility of the nation.”

The next day, Vásquez was taken before a judge and charged with disseminating false information that can “cause panic in the people or maintain them in a state of anxiety.” He was released on condition that he would appear in court “every time it is requested by the court,” but he still faces charges.

Carlos Rosales

On February 5, Carlos Rosales, a physician who is the president of the Venezuelan Association of Clinics and Hospitals, was detained a day after he gave a TV interview about the shortage of medical supplies in Venezuela. During the interview with Globovisión, Rosales said that while health centers were continuing to treat patients, pharmacies had a severe shortage of supplies and half of medical equipment that hospitals have was not functioning properly. These circumstances, Rosales said in the interview, affected both the public and private health care systems and had caused 75 of 234 health centers that belong to his association to suspend elective surgery.

Three intelligence agents went to the Guerra Méndez clinic in Valencia, Carabobo State, where Rosales works, and told him to accompany them to the agency’s headquarters, without presenting a warrant. Rosales was able to call his lawyer on the way, but the agents did not allow the lawyer to be present during the interrogation.

The agents interrogated Rosales about his statements for three hours, then released him. They warned him to “be careful” about what he says because it could “generate alarm in the population.” Under Venezuelan law, causing “panic” or “anxiety” in the population by disseminating “false information” is a crime.

Ángel Sarmiento

In September 2014, Venezuelan officials asked the Attorney General’s Office to investigate Dr. Ángel Sarmiento, the president of the State Bar Association of Medical Doctors of Aragua, after he said in a radio interview that eight people had died in the Central Hospital in the city of Maracay from a disease that had not been diagnosed but caused fever, respiratory problems, and a rash.

Sarmiento’s statements were made at a time when Venezuela was facing a high number of cases of mosquito-transmitted diseases, with the Pan American Health Organization reporting an estimated more than 34,000 suspected cases of chikungunya and 75,000 suspected cases of dengue in 2014. Independent experts suspect there may be many more cases, given that many patients with fever don’t get a proper diagnosis. Doctors and patients told Human Rights Watch that despite government pledges to import medicines to treat these illnesses, people were often unable to get the drugs, particularly during peak demand.

Several governing party officials denounced Sarmiento for his statements. The Aragua governor, Tarek El Aissami, accused the doctor of “initiating a terrorist campaign and generating collective anxiety and shock” and asked prosecutors to open an investigation against Sarmiento, calling him a “spokesman of the fascist opposition.” Delcy Rodríguez, the then national communications minister, called Sarmiento’s declarations “lies seeking to cause distress in the population.”

In response to the governor’s request, Attorney General Luisa Ortega Díaz appointed a prosecutor for the case, and the National Assembly adopted a statement supporting the investigation and denouncing “media terrorism by right-wing factors of the health sector.” Two days later, President Maduro said that such acts of “psychological terrorism” would be “severely punished.”

Sarmiento fled Venezuela.

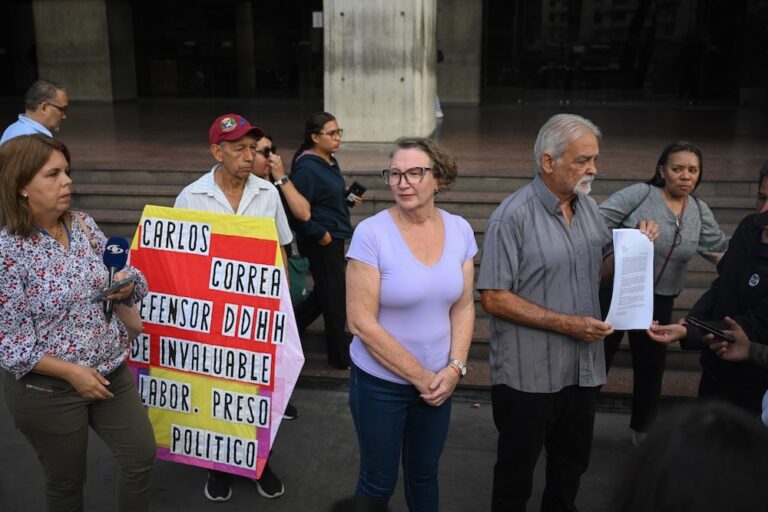

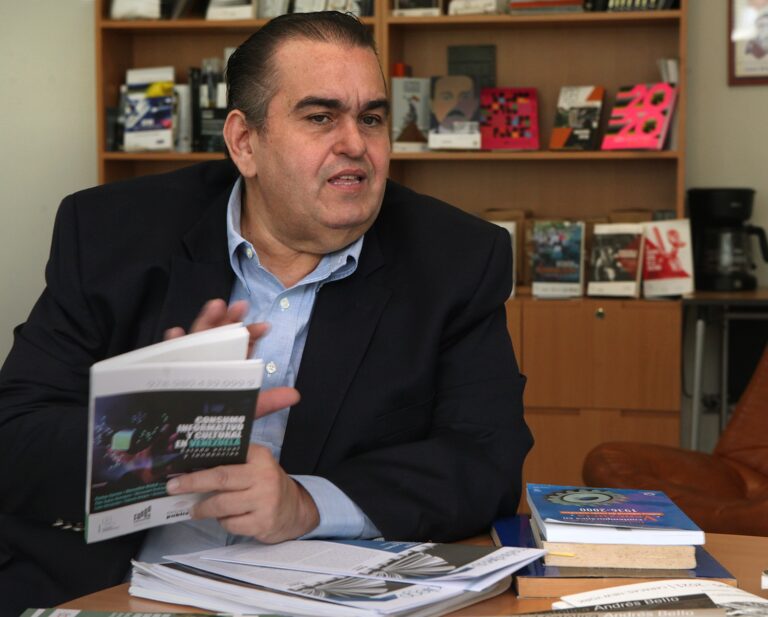

Cabello’s Defamation Suits

In April, Cabello, the Assembly president, filed civil and criminal charges of aggravated defamation against 22 “shareholders, editors, editorial boards, and owners” of the Venezuelan newspapers Tal Cual and El Nacional and the news website La Patilla for reproducing an article by the Spanish newspaper ABC. The article included statements allegedly made by Cabello’s former bodyguard, Leamsy Salazar, who the reports said was allegedly collaborating with US authorities to investigate allegations that Cabello had links to a drug cartel. Cabello claimed that the decision to reprint the accusations is part of an ongoing “international rightwing plan to attack him.”

In May, a criminal judge admitted the case, allowing the criminal investigation of the defamation case to move forward. The judge has prohibited the accused from leaving the country, and required them to report in person to the court every week while the criminal case continues. Four of them – directors of the company that owns Tal Cual, including its editor – and the author of an opinion article published by the paper in January 2014 are also targets of a separate defamation suit Cabello filed earlier.

María Magaly Contreras

In October 2014, María Magaly Contreras, a fortune-teller who has been medically diagnosed with a psychological disorder, was detained by four intelligence agents in Maracaibo, Zulia State, for tweeting messages that, according to a police report, were part of “a plan against the security of the nation.” The tweets cited include a prediction that Fidel Castro, “the dictatorship in Venezuela,” and the person “who originated and brought disgrace” to Venezuela, would die.

Contreras was held in pretrial detention until April 10, when a judge suspended the prosecution on condition that she admitted she published the tweets and agreed to eight months of psychological treatment.