Questions about who committed Arun Singhaniya's murder and why remain unanswered, and his family, which lives in fear, is increasingly desperate to see the case solved.

(CPJ/IFEX) – March 1, 2012 – On the evening of March 1, 2010, Arun Singhaniya, owner of “Janakpur Today” newspaper and Janakpur Today Radio, stepped out of a prayer service during a holy celebration in Janakpur, Nepal’s second largest city. A gunman on a motorcycle shot and killed the news proprietor, making him the second person affiliated with the Janakpur Today news group to be murdered within a year.

Two years later, questions about who committed this crime and why remain unanswered, and his family, which lives in fear, is increasingly desperate to see the case solved.

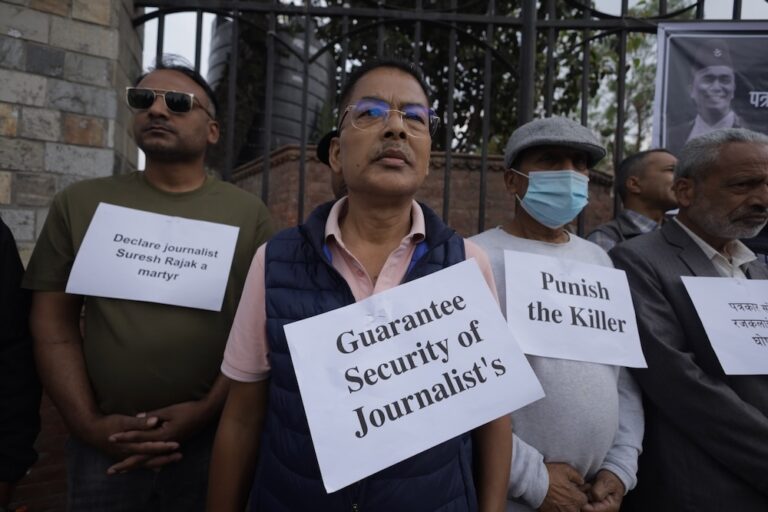

This past week, representatives from 14 international organizations, including CPJ, joined the Federation of Nepali Journalists in a fact-finding and advocacy mission to investigate the case and the many other threats to press freedom in Nepal. In addition to finding that impunity still prevails in the majority of media killings, the team raised concerns over self-censorship, weaknesses in the draft constitution due to be adopted this year, restrictive regulations on Internet usage, and infringements to existing access-to-information laws.

The group met with Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai, the attorney general, and other officials, as well as political party heads, journalists, and members of civil society. We split into smaller teams to visit areas outside the capital Katmandu, where attacks against journalists have been prevalent. I (Elisabeth Witchel of CPJ) joined the five-member team which travelled to Janakpur, where we met the families of Singhaniya and Janakpur Today radio broadcaster Uma Singh, who was stabbed to death by as many as 15 people in 2009.

No one has been arrested for Singhaniya’s murder, and what progress has been made in the case has been obfuscated by inconsistency and lack of transparency. There have been two reports, one by district police and one by a national commission, but neither result has been disclosed publicly nor shared with the family. “There have been false promises. Two years have passed and police have not disclosed anything,” Rahul Singhaniya, Arun’s son, told Geeta Seshu from South Asian Media Solidarity Network and me.

Rahul and other members of the Singhaniya family told us police never took formal statements from them, while a family friend who was with Arun Singhaniya on the day of his killing until just before he stepped outside the prayer meeting and was shot said he was never interviewed by police either.

Police have answered the family’s inquiries with conflicting updates, telling them one day that investigations are near a conclusion and arrests will be made shortly; and on another day that the suspects are in India and beyond reach or that Indian authorities are not cooperating, according to Rahul. “They give us platitudes,” he complained.

Chief District Officer Basant Raj Gautam and District Superintendent of Police Purshottam Kandel confirmed to us that two suspects — Binit Jha, the alleged triggerman, and another figure they would not name — were in India, but said, in contradiction to what has at times been told to the family, that Indian authorities were cooperating on this and other investigative matters.

Both said they were unable to answer questions pertaining to the initial investigation, since they were only recently appointed to this district. The district’s former superintendent of police, Roop Kumar Neupane, was demoted to the rank of inspector and relocated to Kathmandu shortly following his investigation into the murder, amid allegations he was linked to underworld figures — another factor that has raised questions about the case.

Other representatives of the mission spoke with members of two militant groups that have been reported at different times to have been responsible for the murder. Both denied involvement.

Based on the information available, it is not clear whether Singhaniya was killed in connection with his position as owner of two prominent media outlets. His family does not know. They described him as having no enemies, popular, and in good standing with his community. “His nature was to help others all the time,” said Rahul. One person close to Arun told us that he had allowed his newspaper to report extensively on the arrest of a member of his own Marwari community for murder, rather than succumbing to pressure to close ranks.

“Till now, the government has not done anything. At least give us a reason for the killing. We heard the minister of information then say that the death was either due to business or revenge, but we don’t accept that,” said Arun’s father, Badri Prasad Singhaniya, as interpreted by Rahul. “At least they should catch the culprits, whatever the cause may be.”

Singhaniya’s case reflects many of the elements of other media slayings in Nepal: incomplete investigations rife with unanswered questions, and key suspects still at large. Even in cases where some convictions have taken place, main perpetrators and masterminds have not been prosecuted. The International Media Mission called upon stakeholders from the government, civil society, media, and the National Human Rights Commission to develop an independent task force to investigate and ensure that those who attack journalists face justice. In meetings with the mission team, both the prime minister and attorney general said they would consider this.

Meanwhile, the Singhaniya family continues to live in fear. They limit their movements and don’t go out in the evenings. They say this will be so until they find out what happened to Arun.